Problem-Based Learning Discussion (PBLD): Postoperative Pain Management in Patients Undergoing Shoulder Arthroscopy

Editor’s note: We hope you enjoy this third installment of the problem-based learning discussion feature for the ASRA News. We contacted some of the readership to provide responses to the case selected for this feature. To keep this feature going, though, we need your help! 1. Please send deidentified cases you would like to see discussed in this format to the ASRA News at asranewseditor@asra.com. We will collectively choose the most suitable cases for discussion. 2. Please let us know if we can count on you as a contact to reply to cases and provide your opinion on how you would manage said case. Please send your name, practice setting, and contact information to asranewseditor@asra.com. Thanks, and enjoy!

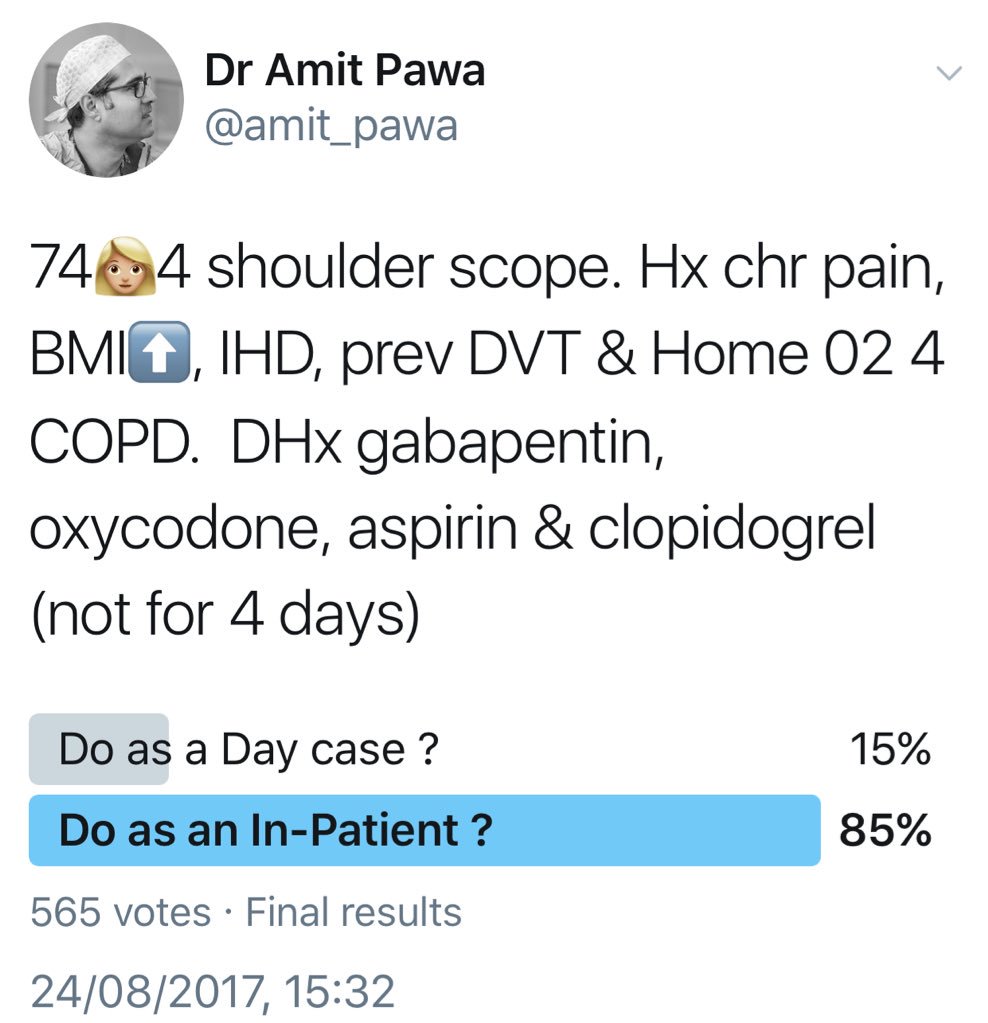

A 74-year-old woman presents for left shoulder arthroscopy. She suffers from chronic shoulder pain, obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 45), coronary artery disease (drug-eluting stent placed 18 months ago), and previous deep venous thrombosis (DVT). She is also using 2 L of oxygen continuously because of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Medications include gabapentin 600 mg every 8 hours, oxycodone 20 mg every 4 hours as needed, metoprolol, simvastatin, aspirin, and clopidogrel, which has been held for 4 days. Her cardiologist deemed her to be at a low risk from a cardiac standpoint and stated that no further cardiac testing is needed before surgery.

Would you prescribe any oral premedications (eg, gabapentin, opioids) prior to the surgical procedure?

Dr Auyong: Multimodal analgesics are an important part of managing perioperative pain. For most outpatient shoulder surgeries, I like to administer acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) prior to surgery. Typically, I do not give gabapentin for outpatient surgeries because of the risk of postoperative sedation. However, in a patient who is already on gabapentin and oxycodone, I would not hesitate to ensure she took those medications preoperatively as well.

Dr Maniker: I would ensure that she has taken her gabapentin on the morning of surgery and would prescribe preoperative 1 g oral acetaminophen and 200 mg celecoxib.

Dr Harrington: This patient would be given 1,000 mg oral acetaminophen prior to surgery. She would also be instructed to take her usual 600 mg gabapentin preoperatively. An NSAID (oral celecoxib or intravenous ketorolac) would be used on a case-by-case basis in consultation with the surgeon.

Dr Pawa: Under normal circumstances for this type of surgery, I would not routinely prescribe oral premedication. In this particular instance, in the context of preexisting chronic pain, preoperative opioid and gabapentin use, and significant respiratory disease, I would prescribe at least her usual drugs prior to the surgical procedure so at least I would be starting at her baseline.

Would you offer a regional anesthesia technique? Which block? Would you use a catheter?

Dr Auyong: I would absolutely offer a regional anesthesia technique for postoperative analgesia. My approach would be a continuous suprascapular catheter via an anterior approach. My research team and I have recently completed two studies evaluating the anterior approach to the suprascapular nerve, one of which was published this year. We showed that continuous suprascapular catheters had equivalent analgesic efficacy as interscalene catheters but preserved at least 82% of vital capacity after 24 hours of continuous infusion compared with only 62% for interscalene catheters. Therefore, in this patient with restrictive lung disease secondary to obesity and preexisting COPD, I would prefer an anterior approach suprascapular nerve catheter for analgesia while maximizing our chances at preserving her lung function.

Although regional anesthesia could be used for surgical anesthesia, the patient's baseline oxygen requirement, her obesity, and the sitting position used for shoulder arthroscopy would make any additional airway support during the case difficult. Therefore, I would prefer to secure her airway from the beginning of the case and use general anesthesia (GA).

Dr Maniker: Yes, I would recommend long-acting, single-shot, combined infraclavicular and suprascapular nerve blocks. I would avoid interscalene or supraclavicular block because the patient has a low pulmonary reserve (given her continuous oxygen requirement) and would likely not tolerate ipsilateral phrenic block. Infraclavicular block would cover the axillary nerve, as well as lateral pectoral and upper and lower subscapular nerves. When combined with a suprascapular nerve block, this should provide good postoperative analgesia and only spares the supraclavicular nerves from the superficial cervical plexus. I would consider catheters but would need to further discuss issues, including coagulation status, plan for timing of hospital discharge, and interference with the surgical field.

Dr Harrington: I am concerned about respiratory reserve as well as platelet function (in the face of clopidogrel plus aspirin). A regional technique of single-shot suprascapular block plus surgical wound infiltration would be encouraged.

Dr Pawa: There are clearly several options for anesthesia and analgesia here with a number of potential risks and complications. My concerns with a classic interscalene block as the sole mode of anesthesia here relate to the impact of phrenic nerve palsy on her COPD and her being able to tolerate this perioperatively. One option is to perform a single-shot interscalene or superior trunk block and use a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) mask perioperatively to support respiration. I would also be aware that performing a plexus block with clopidogrel use within 7 days also makes the risk of hematoma a concern and would dissuade me from using a catheter.

I could do the interscalene and combine it with GA, or my backup plan would be to perform ultrasound-guided suprascapular and axillary nerve blocks supported by sedation or a GA. These techniques may be challenging in someone of her size, but a clear risk-versus-benefit discussion with the patient would help me reach a decision.

How does the presence of clopidogrel, elevated BMI, and history of chronic pain influence your decision?

Dr Auyong: Whenever confronted with a difficult decision, I try to look at this from the patient's perspective. First, in regard to the clopidogrel, there is always a balancing act between anticoagulation, risk of recurrent clots (DVT or pulmonary embolism), risk of stent thrombosis, and risk of procedural bleeding. For a compressible nerve block that has significant analgesic or outcome benefit for the patient, I would proceed with the nerve block despite not having been off clopidogrel for 5 to 7 days.

Second, this patient has several comorbidities (obesity and chronic pain) that, if combined with poor postoperative analgesia, could place her at significantly higher risk for postoperative complications. The alternative primary analgesic is using opioids, which comes with obvious unwanted side effects. Obesity is the most common cause of restrictive lung disease, and patients with restrictive lung disease are most reliant on diaphragmatic movement for ventilation. Therefore, obese patients are most affected by hemidiaphragmatic paralysis seen in brachial plexus regional anesthesia.

To better assess the effect of possible hemidiaphragmatic paralysis on this patient, I would place a suprascapular catheter using a short-acting local anesthetic (lidocaine or chloroprocaine). I would then monitor the patient and evaluate the effect of the nerve block for 20 minutes. If the patient has clinical dyspnea, it indicates that she is unable to tolerate any decrease in diaphragm function. In this scenario, I would not initiate the continuous infusion through the catheter because of the poor clinical outcome of phrenic nerve paralysis in this patient. If the patient does well and does not have side effects from the bolus of local anesthetic, I would start the continuous infusion via the suprascapular nerve catheter.

Finally, in regard to her chronic pain, I know her preoperative reliance on opioids also increases her postoperative risk for complications, especially in the setting of obesity. Her history of chronic pain makes me all the more apt to offer regional anesthesia via a continuous catheter.

Dr Maniker: Because clopidogrel has not been held for 7 days, an increased, albeit low, risk of bleeding remains because of platelet inhibition. Additionally, nerve blocks in this case are at relatively peripheral and compressible locations. Furthermore, these decisions require the weighing of overall risk and benefit. Avoiding peripheral nerve blocks would result in administration of more opioids in the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods and risk significant respiratory depression in this patient with morbid and extreme obesity (class III). Given these considerations, I would still proceed with peripheral nerve blocks.

Dr Harrington: I would be reluctant to perform any brachial plexus block if clopidogrel was discontinued fewer than 5 days prior without first documenting a normal platelet function assay.

Because of her elevated BMI, decreased functional residual capacity and respiratory reserve make any brachial plexus block above the clavicle (interscalene or supraclavicular block) hazardous.

This patient has chronic pain with significant opioid tolerance, making regional techniques attractive. I would definitely administer ketamine intraoperatively.

Dr Pawa: The chronic pain history emphasizes the importance of maintaining her usual drug therapy in the perioperative period and would steer me toward using a regional anesthesia technique in some way if only to minimize her additional opiate requirement. The use of dual antiplatelet therapy within 7 days does induce a mild amount of anxiety, and the potential for a deep plexus in view of her BMI may steer me more toward the peripheral techniques (suprascapular nerve and axillary nerve).

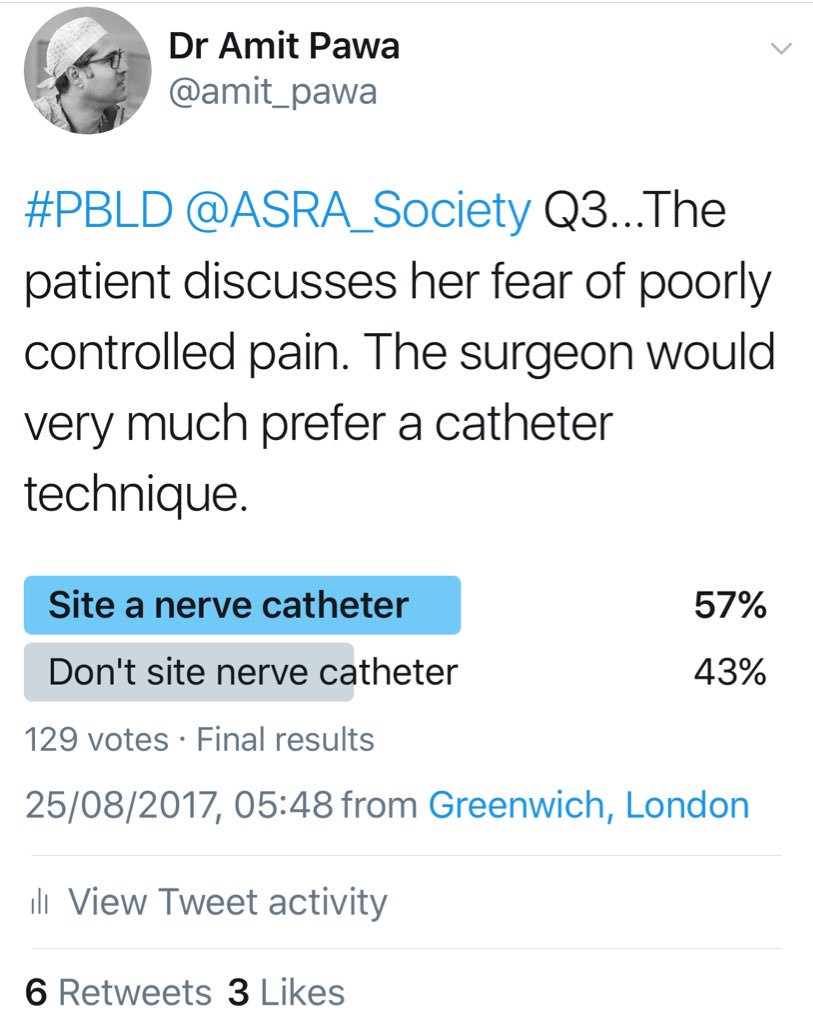

The patient discusses with you her fear that her pain has been incredibly poorly controlled with previous surgical interventions and that this frightens her more than other potential complications. The surgeon approaches you and would very much prefer a catheter technique.

Would this impact your willingness to perform this technique, and if so, how? Why?

Dr Auyong: The focus should be on what is best for the patient, not the surgeon. I would plan on a continuous catheter technique after discussing risks, benefits, and options with the patient.

Dr Maniker: Infraclavicular and suprascapular catheters are reasonable to consider, given the patient's chronic pain and opioid tolerance as well as her pulmonary disease, which would render the negative respiratory effects of opioids particularly deleterious for her in the postoperative period. This would require further discussion with the patient as well as with the surgeon regarding any interference of the catheters on the surgical field.

Dr Harrington: In my hands, the only effective catheter technique under these circumstances would be a continuous interscalene block. Because of the pulmonary risks involved, if an interscalene catheter was considered necessary, I would insist that the procedure be performed as an inpatient.

Dr Pawa: Clearly, my aim would always be to deal with the patient's concerns and deliver the safest and most appropriate anesthetic. I would establish which techniques had been used before and why they had been ineffective. If I was sure that she had understood the risks involved and this was clearly documented, I would carefully perform a catheter technique. The only additional advantage of a catheter technique in this context is that there has been at least one case report where postoperative compromising phrenic nerve palsy was reversed by administration of saline via the interscalene catheter.

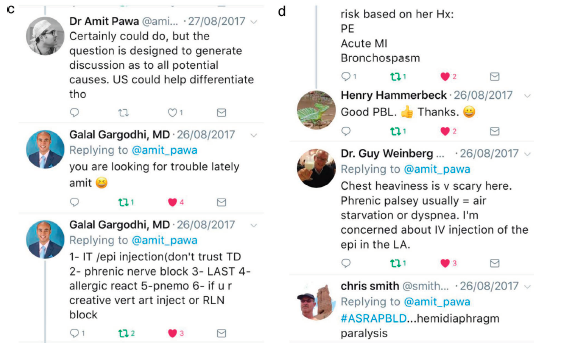

Following placement of an interscalene catheter, negative test dose, and catheter dosing with 10 mL 0.5% bupivacaine, the patient is brought to the operating theater. The patient assumes a fully supine position while transferring to the operating room table and describes significant chest heaviness.

What is in your differential diagnosis?

Dr Auyong: The differential diagnosis is wide ranging and includes cardiac, pulmonary, and neurologic issues. Top on the differential is hemidiaphragm paralysis from phrenic nerve impairment. As previously indicated, an interscalene catheter was placed and dosed with a long-acting local anesthetic. Based on the time frame to the onset of symptoms and the patient's position, I would be most concerned about diaphragm paralysis.

Dr Maniker: Highest on the differential would be symptomatic phrenic block. Other possibilities include myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, anxiety, pneumothorax, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Dr Harrington: The differential would include unilateral phrenic nerve paresis, symptomatic coronary artery disease, and pneumothorax.

Dr Pawa: In this scenario, the differentials would be cardiac chest pain, phrenic nerve palsy, pneumothorax, and intrathecal spread of local anesthetic.

Is there anything you could have changed regarding this patient's care that may have reduced the probability of this outcome?

Dr Auyong: These are the things I would have done rather than placing an interscalene catheter with bupivacaine: (1) anterior approach suprascapular catheter, (2) dosing of the catheter with short-acting local anesthetic (lidocaine or chloroprocaine), (3) small-volume, intermittent dosing of catheter (<5 mL).

Dr Maniker: Interscalene block could have been avoided to prevent phrenic nerve blockade.

Dr Harrington: Although it may not have made any difference, I would not use a high concentration of local anesthetic (0.25% bupivacaine would probably be as effective as 0.5%). Furthermore, I would use a shorter-acting local anesthetic agent, such as mepivacaine or lidocaine, so that if severe pulmonary compromise ensues, it will be shorter lived.

Dr Pawa: Potentially, I could have used a slow, incremental loading of the catheter with a lower concentration of local anesthetic (assuming regional anaesthesia was being used as the sole mode of anesthesia). If the interscalene catheter was being used for analgesia only, I would avoid a bolus dose and start the local anesthetic infusion alone without bolus.

An electrocardiogram and chest x-ray fail to demonstrate any significant abnormalities other than an elevated left hemidiaphragm. The patient is more comfortable with the head of the bed elevated and with the provision of supplemental oxygen.

Would you proceed and induce general anesthesia?

Dr Auyong: Yes, I would proceed with induction of a general anesthetic. Hemidiaphragmatic paralysis is a known side effect of brachial plexus regional anesthesia. If the patient was clinically unstable, I would consider an infusion or bolus of saline through the catheter to dilute the local anesthetic already delivered to help decrease the duration and severity of the side effects related to the block.

Dr Maniker: If the patient was hemodynamically stable and oxygenating appropriately, I would proceed.

Dr Harrington: Yes. Although I generally do these cases with a laryngeal mask airway, I would intubate this patient.

Dr Pawa: If the patient was expecting awake surgery, and assuming the block is effective, I would attempt the use of a CPAP mask or of high-flow, humidified nasal oxygen, and proceed. If the patient was expecting a general anesthetic, I would induce anesthesia.

The surgical procedure is uncomplicated, and no additional intraoperative opioids are required. At the conclusion of the case, the patient is extubated and transferred to the postanesthesia care unit, where her oxygen saturation is noted to be 88% on 2 L nasal cannula. The patient is asymptomatic, but her oxygen saturation fails to improve over the course of 3 hours.

The procedure was planned to be performed on an ambulatory basis. With the removal of supplemental oxygen, the patient's oxygen saturation falls to 86%.

Would you be comfortable discharging the patient home?

Dr Auyong: First, I would check the patient's preoperative oxygenation. Next, if these oxygen saturation values are significantly lower than her preoperative baseline, I would give the patient some time, incentive spirometry, and better positioning (sitting upright or standing) to improve her oxygenation. However, in the setting of this patient's multiple comorbidities and lack of improvement in her postoperative course with time, I would recommend the patient be admitted overnight.

Dr Maniker: This depends on the patient's baseline oxygen saturation. If it is close to baseline, I would recommend temporarily increasing the supplemental oxygen and discharge with close watch by a family member or caretaker. If this is a significant change from the patient's baseline and does not improve with increased supplemental oxygen, I would have the patient admitted for observation overnight.

Dr Harrington: No. As previously stated, I would not be comfortable doing this case at an ambulatory center if an interscalene block was planned.

Dr Pawa: No.

Would you be comfortable initiating an infusion of local anesthetic through the interscalene catheter?

Dr Auyong: No, because bupivacaine was already dosed and no additional opioids have been required, I would not elect to initiate a continuous infusion of local anesthetic via the interscalene catheter at this time. Because the patient has hemidiaphragmatic paralysis, additional dosing may delay her improvement in pulmonary function and postpone her discharge further. Continuous infusion of local anesthetic is similarly associated with phrenic nerve impairment as a single-injection bolus at the interscalene level. I would, however, leave the catheter intact for future dosing.

Dr Maniker: No. Interscalene catheters have been associated with phrenic block and respiratory events, even if the initial bolus doses did not result in symptomatic pulmonary compromise.

Dr Harrington: At this point, the catheter appears to be functioning well. Although I would usually initiate a low-volume infusion for a case like this, in this patient I would not start a baseline infusion but would prefer to first try a patient-controlled intermittent bolus technique (4 mL 0.2% ropivacaine with a 60-minute lockout).

Dr Pawa: I would leave the catheter in situ and only cautiously commence an infusion, or administer a low-volume bolus if pain became an issue overnight. This patient would have continued administration of low-flow oxygen and vital signs measurement monitoring throughout.

If yes, what would your infusion strategy be?

Dr Auyong: Options for infusion would be (1) intermittent, lowvolume bolusing of the interscalene catheter as needed (no continuous rate), (2) infusion of chloroprocaine so any clinical symptoms of phrenic paralysis would be short lived, or (3) replacing the interscalene catheter with a more distal brachial plexus approach such as a suprascapular catheter.

Dr Maniker: If the catheter was used, the infusion should be initiated with very low volume and in a well-monitored setting.

Dr Harrington: As before: no baseline infusion with a patientcontrolled intermittent bolus (4 mL 0.2% ropivacaine with a 60-minute lockout). Continue multimodal therapy (acetaminophen plus gabapentin) on a scheduled basis, with oxycodone available PRN. If this approach was inadequate, I would begin a low-volume infusion of ropivacaine (4 mL/hr) on top of the patient-controlled intermittent bolus.

Dr Pawa: I would use infusion of a low-volume, low-concentration solution such as 0.125% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine at 4–5 mL/hr.

A low-volume infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 4 mL/hr is initiated, and the patient is transferred to the floor for observation and supplemental oxygen administration. The following day, the patient's oxygen saturation has now normalized and she is prepared for discharge. The surgeon, after further discussions with cardiology, would like to restart clopidogrel therapy immediately.

Do you have any concerns sending a patient home with an interscalene catheter while on clopidogrel? Warfarin? Low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH)? If you have treated these differently, why?

Dr Auyong: In general, if patients are on anticoagulation, I recommend removal of continuous nerve blocks upon discharge home. However, this patient is now asymptomatic and likely receiving significant analgesic benefit from the continuous nerve block. It appears that discharging this functioning continuous block is in the best interest of the patient. I would discuss the risks, benefits, and options for analgesia with the patient and if she understood, would allow discharge home with anticoagulation. Because this is an interscalene block at a compressible area, I am less concerned about a small hematoma from the catheter remaining in place and eventually being removed. It is important that the patient and her caregiver understand the risks of going home with the nerve block while anticoagulated. If the patient had a follow-up appointment with the surgeon within the next few days, I would recommend removal of the catheter while in the surgeon's office.

Dr Maniker: I would be hesitant to send this patient home with an interscalene catheter given the risk of symptomatic phrenic paresis and the impact on pulmonary function. In addition, perineural bleeding from catheter or its removal would not be recognized and therefore I would not send the patient home with a catheter if anticoagulated with clopidogrel or warfarin.

Dr Harrington: I would like to hold clopidogrel until the catheter is removed. Prophylactic dose LMWH (40 mg/d) would be preferable and recommended. Although warfarin would be acceptable for a few days (because of its delayed effect), it doesn't appear to be indicated in this case.

Dr Pawa: I have major concerns with clopidogrel and warfarin and indwelling catheters. Once those therapies are reinstituted, intentional or unintentional catheter removal could be problematic.

Prophylactic LMWH is a once-a-day therapy, and at least planned catheter removal can be carefully planned 12 hours after last dose.

Following a discussion with the surgeon and cardiologist, the decision is made to send the patient home with aspirin and LMWH therapy until the interscalene catheter is removed. The patient lives three blocks from the hospital, and the patient's daughter is an internist who vows to monitor the catheter site closely for any signs of bleeding. The patient is sent home with an indwelling interscalene catheter. Following a successful 3-day ambulatory infusion, it is now time for the interscalene catheter to be removed.

What steps or precautions do you normally take at the time of peripheral nerve catheter removal (eg, pausing infusion, family member to assist with removal, coached on phone)?

Dr Auyong: Normally, we give instructions for catheter removal preoperatively and in the recovery room. Additionally, we call the patient daily as long as the continuous nerve catheter is in place. After the continuous infusion is complete, we typically have the patient's caregiver pull the catheter at home. If, however, the patient is uncomfortable performing catheter removal at home, we offer to talk the patient through the procedure on the phone or have the catheter removed in the surgeon's office during the follow-up visit.

Dr Maniker: Patients are instructed prior to hospital discharge and over the phone about catheter removal as well as monitoring after removal. The patient is instructed to contact the service if any evidence of bleeding, swelling, significant erythema, or paresthesia develops or if the denseness of numbness increases over time.

Dr Harrington: Normally, patients can remove the catheter themselves after the home infusion is complete. It would not be uncommon to have a patient who lives this close return to the hospital for catheter removal. In this particular case, the patient's daughter would ideally remove the catheter, if she's comfortable.

Dr Pawa: I do not send patients home with ambulatory catheters in my current practice, and so my answers to this would not be based on my experience. I would be more comfortable with coached removal over the phone that was assisted by a family member (assuming adequate preoperative training).

Does the presence of LMWH therapy alter your planning?

Dr Auyong: I would recommend pulling the continuous catheter during the trough, prior to the next dose of LMWH. I would instruct the patient to apply pressure if bleeding starts or persists at the catheter insertion site. If the patient is uncomfortable with pulling the catheter at home, I would suggest having the catheter pulled in the surgeon's office at the follow-up visit.

Dr Maniker: In this case, given that the daughter is a physician, I would feel comfortable with the daughter assisting in catheter removal and monitoring the site afterward.

Dr Harrington: Removal of the catheter should be timed to be no sooner than 10–12 hours after the last dose of LMWH.

Dr Pawa: Yes, assuming a once-daily dosing, I would want the catheter removal to be at least 12 hours after last dose.

Resistance is encountered with attempted catheter removal.

What steps do you take when resistance is encountered with attempted catheter removal, and how do you plan to remove it?

Dr Auyong: If resistance is encountered, we have patients change position and try pulling the catheter again. Often a simple position change assists in helping the catheter slide out. If the catheter continues to have resistance, we offer to have the patient present to us for catheter removal or to have the catheter removed during their follow-up appointment in the surgery clinic. If the catheter was indeed stuck, I would ensure a member of the peripheral nerve catheter team was present at the surgical appointment to assist in the catheter removal.

Dr Maniker: Gentle continuous traction is first applied. Next, arm movements such as abduction as well as neck flection and extension can be attempted while providing gentle catheter traction. Next, a small amount (3–5 mL) of preservative-free sterile normal saline can be injected through the catheter, which has been reported to aid in removal of peripheral nerve catheters. This can also be performed under ultrasound to visualize the catheter trajectory. Unfortunately, catheters can become knotted and in rare cases may require surgical removal.

Dr Harrington: Although catheters can usually be removed by patients at home, if any resistance is encountered, the catheter should be removed only by anesthesia personnel. Steady tension on the catheter is advised.

Dr Pawa: In this instance, I would advise the patient to return to the hospital and aim to use ultrasound or x-ray to determine whether the catheter had kinked or knotted. If no knotting or kinking were found, I would apply continuous steady traction.

How would this be altered if the patient complained of paresthesias with attempted catheter removal?

Dr Auyong: If paresthesias were encountered during catheter removal, I would not allow further traction or pulling on the continuous catheter. I would have the patient present in person for evaluation by myself and the peripheral nerve catheter team. My evaluation would entail a physical exam and ultrasound exam of the brachial plexus (with and without traction on the catheter). If paresthesias persisted without the ability to remove the catheter, I would consult my neurosurgical colleagues for further evaluation and possible surgical removal.

Dr Maniker: I would stop traction on the catheter. The catheter could be knotted and either wrapped around a nerve or positioned in a way that contacts or compresses a nerve. Patient positioning could be changed with very gentle traction, which is again stopped with any patient report of paresthesia. As previously mentioned, ultrasound could be used to define the course of the catheter, but surgical consultation may be needed to remove the catheter.

Dr Harrington: In that case, I would be concerned about knotting. I would try to visualize the catheter by injecting a small volume of contrast material under fluoroscopic guidance. Imaging would provide guidance as to the safest means of removing the catheter.

Dr Pawa: I would cease pulling and ask for a surgical opinion.

How would you proceed if you attempted to remove the catheter and you think you left a portion behind in the patient?

Dr Auyong: If a portion of the catheter was left behind in the patient, I would first and foremost inform the patient. If asymptomatic, I would reassure the patient that retained foreign bodies are generally not removed surgically. I would examine the patient with ultrasound to see if I could locate any part of the catheter and document in the patient's medical record. Unless the retained catheter caused symptoms, I would not push forward with any further evaluation.

Dr Maniker: I would obtain imaging (bedside ultrasound and possible computed tomography) and consider obtaining a surgery consult for exploration and removal.

Dr Harrington: A surgical consult would be obtained for open removal of the broken fragment.

Dr Pawa: I would organize imaging and a consultation with my surgical colleagues, with a view to facilitate surgical removal if required.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top