Ankle Block

Artemus Flagg II, MD, MPH

Anesthesiology Resident

Calvin Eng, MD

Instructor

Vineesh Mathur, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Baltimore, MD

Introduction

An ankle block represents a regional anesthetic technique designed to provide surgical anesthesia for many types of foot operations. It is principally an infiltration block and does not require elicitation of paresthesias.[1] There are many advantages of the ankle block technique, which include:

- technical ease,

- high safety factor with minimal side effects,

- near 100% success rate,[2]

- typically does not require multiple injections, and

- can be taught to the relatively unskilled.[3]

To decrease procedure related pain and anxiety, a combination of a short acting benzodiazepine and a narcotic, given in titrated doses, is recommended. In diabetic patients with severe neuropathy, the absence of normal sensation does not preclude the use of the ankle block procedure. When ankle blocks are necessary in these patients, their efficacy may actually be enhanced because of the preexisting diminished sensation in the affected foot.[4]

Ankle blocks can provide reliable anesthesia for foot surgery in patients with multiple medical problems. The block is devoid of any major physiological consequences that may be associated with axial or more central blocks.[5] Even though ankle blocks are often recognized as “volume” blocks due to the administration of a large volume of local anesthetic to achieve a complete block, a lower concentration of local anesthetic may be utilized because motor blockade is often not needed for the surgical procedure.

Anatomy

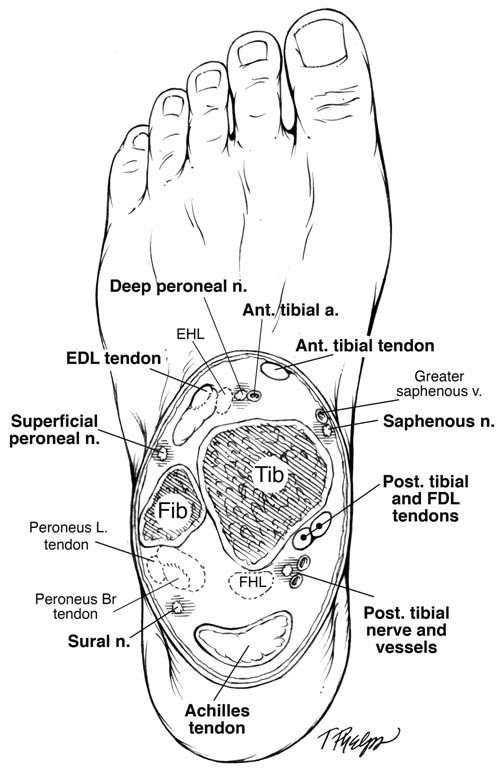

Familiarity with the anatomy and innervation of the foot allows for a more precise localization of the nerves around the ankle, resulting in a higher success rate.[6] Five peripheral nerves provide sensory innervation to the foot and are relatively easy to block at the ankle. Four of the nerves are branches of the sciatic nerve; these are the posterior tibial, deep peroneal, sural, and the superficial peroneal nerves (Figure 1). The fifth nerve is the saphenous nerve, which is a sensory branch of the femoral nerve. With the exception of the saphenous nerve, an ankle block can be viewed as a block of the terminal branches of the sciatic nerve.

Figure 1. Ankle cross-sectional image. The figure at the level of the malleolus shows the typical distribution of the terminal branches of the sciatic and femoral nerves that comprise the ankle.

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. 2010

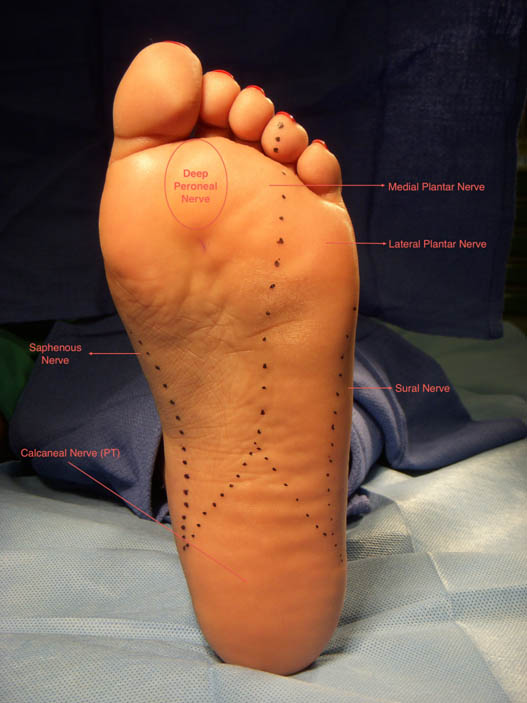

Achieving a complete ankle block involves anesthesia of all five nerves with the posterior tibial nerve being the major nerve of interest as it innervates all five toes.[6] The cutaneous innervations of these nerves supplying the foot are as follows (Figure 2):

- The posterior tibial nerve provides sensory innervation to the plantar surface of the foot and toes by its three divisions: the medial plantar nerve, lateral plantar nerve, and medial calcaneal nerve.

- The deep peroneal nerve supplies sensation to the dorsum of the foot between the great and second toe.

- The superficial peroneal nerve supplies sensory innervation to the dorsum of the foot and toes, except the web space between the first and second toes and the lateral aspect of the foot.

- The sural nerve provides sensory innervation to the lateral surface of the foot and the heel.

- The saphenous nerve provides sensation to the skin over the medial malleolus, medial surface of the foot up to the medial arch, and to the medial side of the great toe.

Figure 2. Cutaneous innervation of the foot.

Indications

The ankle block is a regional block designed to provide anesthesia for a variety of surgeries performed on the foot or toes.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications of performing an ankle block include patient refusal and infection at the injection site(s). The ankle block should be avoided if a proximal high-pressure tourniquet is required for the surgical procedure because the blocks will not provide relief of tourniquet pain that might occur with the thigh tourniquet. In addition, epinephrine-containing solutions should be avoided during circumferential injections of the ankle because of a potential risk of compromising the distal vascular supply in the foot. Lastly, the ankle block will not provide coverage for the extrinsic muscles of the foot.

Technique

Materials

- Appropriate resuscitation equipment and medications

- Surgical prep

- Sterile towels and gauze packs

- Sterile gloves and mask

- Marking pen

- Three 10-ml syringes (control or ring syringes are preferable)

- (3) 25-gauge, 3.8 cm needle

- 18-gauge needle

- Local anesthetic

Technical Considerations

After placing the patient in the supine position, the entire foot should be prepped using an aseptic technique. The use of a controlled syringe and manipulation of the foot with the “non-injecting” hand may facilitate optimal positioning of the foot when blocking the posterior tibial and sural nerves. This should alleviate the need to place the patient in the prone position. If positioning issues persist, the lower leg can be placed in a padded support or elevated by an assistant.

The posterior tibial nerve and deep peroneal nerve are blocked first to reduce the onset time of the complete block. Also, subcutaneous injection for the superficial blocks will distort the anatomy potentially resulting in added delay.

Posterior Tibial Nerve

The posterior tibial nerve is the most important and most difficult nerve to block to ensure adequate surgical anesthesia. The tibial artery pulsation is palpable at the space between the posterior border of the medial malleolus and the medial border of the Achilles tendon.[7] A 25-gauge, 3.8 cm needle is inserted inferiorly at about 60 degrees to the skin immediately posterior to the artery, penetrating 1 to 1.5 cm. Following negative aspiration 3–5 mL of local anesthetic is injected (Figure 3). The needle is now pulled back to the skin and redirected toward the great toe. Following a negative aspiration an additional 3–5 mL is injected. This fan technique can be utilized to increase the success rate.[7]

Figure 3. Posterior tibial nerve block.

Deep Peroneal Nerve

The deep peroneal nerve and dorsalis pedis artery lie between the anterior tibial and extensor digitorum longus tendons. The nerve usually lies just lateral to the artery, which is used as a landmark (Figure 4). If the artery is not palpable, the anterior tibial tendon, which is large and lies adjacent to the subcutaneous border of the tibia, can serve as a landmark. The skin is entered immediately lateral to the artery with a 25-gauge 3.8 cm needle. The nerve is typically 1 to 1.5 cm deep to the skin. After confirming a negative aspiration, 3–5 mL of local anesthetic is injected.7 Skin blanching on injection should not be observed as this signifies a rather superficial injection.

Figure 4. Deep peroneal nerve block

Sural Nerve

The sural nerve is blocked by inserting a 25-gauge, 3.8 cm needle, lateral to the Achilles tendon at the cephalad border of the lateral malleolus. 3–5 mL of local anesthetic is injected superficially posterior to the lateral malleolus in a field-like distribution with the goal of creating a ring of anesthesia once the superficial and saphenous nerves have been blocked (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Sural nerve block

Superficial Peroneal Nerve

Placing a subcutaneous ridge of local anesthetic from the anterior tibia to the lateral malleolus blocks the superficial peroneal nerve (Figure 6). A total of 5 to 10 mL may be required to cover the 5 to 7 cm necessary to anesthetize all the superficial fibers.[8] The same area, which was previously anesthetized during the deep peroneal nerve block, can be used as an entry point for blocking the superficial peroneal nerve.

Figure 6. Superficial peroneal nerve block

Saphenous Nerve

The saphenous nerve can also be blocked utilizing this midline entry point.[9] Inject 3–5 mL of local anesthetic from a 25-gauge, 3.8 cm needle while advancing the needle medially at the level of the medial malleolus between the skin and bone itself (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Saphenous nerve block

Choice of Local Anesthetic

The duration of surgery and the required duration of postoperative analgesia are important considerations in the selection of local aesthetic agents for ankle blocks. Long-acting preparations (0.5–0.75% bupivacaine and 0.75–1.0% ropivacaine) are commonly used to satisfy both goals. Commonly used intermediate acting preparations include 1–2% lidocaine and 1.5% mepivacaine.

Complications

Neuropathy may occur in patients who receive ankle blocks, which may result from accidental intraneuronal injection or pinning the nerve against the bones with the needle at the time of injection.[9] New paresthesias that do not resolve represent a rare but significant complication.

Aspiration prior to injection minimizes the risk of local anesthetic toxicity resulting from direct intravascular injection. Despite being referred to as a “volume” block, local anesthetic plasma levels are relatively low following an ankle block. Previous studies have found that minimal detectable levels of lidocaine and bupivacaine were measured in venous blood after both unilateral and bilateral midtarsal blocks despite using near maximal doses of local anesthetic recommended for these agents.[2]

Summary

The ankle block is a safe and reliable procedure capable of providing adequate anesthesia for many types of foot operations. The benefits of reducing intraoperative risks to patients who are poor candidates for general and neuraxial anesthesia while providing optimal pain control with minimal side effects, and potentially reducing the cost of postoperative services by allowing for an early return to ambulatory function, makes this technique an excellent option for the patient and anesthesiologist.

References

- Brown D. Atlas of regional Anesthesia, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1999 : 17: 139 -143

- Mineo R, Sharrock N: Venous levels of lidocaine and bupivacaine after midtarsal ankle block. Reg Anesth 1992; 17: 47-49

- Sharrock N, Waller J, Fierro L: Midtarsal block for surgery of the forefoot. Br J Anaesth 1986; 58: 37-40

- Reilley AT, Gerhardt M: Anesthesia for foot and ankle surgery. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery 2002; 19: 125-147

- Sarrafian S, Ibrahim I, Breihan J: Ankle-foot peripheral nerve block for mid and forefoot surgery. Foot and Ankle 1983; 4: 86-90

- Benzon HT et al: Essentials of Pain Medicine and Regional Anesthesia, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill-Livingstone 2005; 78: 672-676

- Canale, Beaty: Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, 11th ed. 2007; 77: -

- Mulroy M: Regional Anesthesia: An Illustrated Procedural Guide, 3rd ed. 2002; 16 217-223

- Kay J: Ankle Block. Techniques in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Management 1999; 3: 3-8