How I Do It: Anterior Suprascapular Block, Superior Trunk, and the Significance of the Suprascapular Posterior Anterior Anatomy

Cite as: Auyong D. How I do it: anterior suprascapular block, superior trunk, and the significance of the suprascapular posterior anterior anatomy. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2022;47. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020122.004.

Anterior suprascapular blocks provide analgesia for shoulder surgeries, including arthroscopy, rotator cuff repair, and shoulder replacement. As the name implies, the nerve block targets the suprascapular nerve from an anterior or proximal approach, close to where it originates from the brachial plexus along the superior trunk or nerve root of C5.

The anterior block location is different than other suprascapular nerve blocks that target the scapula spine or the scapular notch, usually from a more posterior approach. Because those blocks use a posterior needle insertion, axillary nerve block is often recommended to provide additional analgesia to the shoulder.1 With an anterior suprascapular block, the local anesthetic is placed near the suprascapular nerve’s origin, close to the divisions of the superior trunk, which allows the local anesthetic to track to other nerves that bring afferent nociception from the shoulder joint.

The gold standard for shoulder analgesia has long been an interscalene block, which has been associated with hemidiaphragmatic paralysis for more than a century.2 Although the adverse event is usually tolerated in patients without underlying respiratory comorbidities, when combined with peripheral nerve catheters or long-acting nerve blocks and the obesity epidemic, hemidiaphragmatic paralysis’s clinical symptoms are more pronounced in certain patient populations. However, certain strategies may decrease phrenic paralysis symptoms after brachial plexus nerve blocks.3

Anterior suprascapular block can provide noninferior analgesia and preserve lung function compared to interscalene block after major arthroscopic shoulder surgery. A more distal and lateral placement of local anesthetic along the brachial plexus can reduce the incidence of phrenic nerve palsy because the nerve is proximal in origin and medial in location to the distal brachial plexus, and it also provides noninferior analgesia compared to a more proximal interscalene block.4

Anatomy

Understanding the analgesic efficacy of various brachial plexus nerve blocks for shoulder surgery begins with the afferent innervation of the shoulder. The primary nerves bringing afferent signals innervating the shoulder are the suprascapular, axillary, lateral pectoral, and subscapular nerves.5,6 Older theories suggest that the suprascapular nerve is the primary afferent nerve, carrying up to 70% of shoulder joint innervation.7 However, more recent theories suggest that the other three nerves also have a major role in bringing afferent signals from the shoulder joint nociceptors.8 Therefore, isolating only the suprascapular nerve for local anesthetic injection may not result in optimal shoulder analgesia, and pain physicians must consider the other afferent shoulder joint nerves when performing nerve blocks.

The brachial plexus is complex and often varies from patient to patient, which can be confusing even for surgeons who reconstruct its nerves after traumatic injury.9 Recent findings suggest that the suprascapular nerve’s origin is more closely related to the posterior division of the superior trunk,9 which is contrary to previous diagrams that suggested it was in closer proximity to the anterior division. The anatomic significance of the suprascapular nerve originating near the posterior division of the superior trunk suggests that local anesthetic placed nearby may result in some blockage of the posterior division as well. This is important because the axillary and subscapular nerves eventually originate from the posterior cord, supplied in part by the superior trunk’s posterior division.

The lateral pectoral nerve is a fourth terminal nerve that is a significant contributor to shoulder nociception. It usually arises from the lateral cord or the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks, and its fibers originate from C5, C6, or C7.10

The suprascapular nerve and divisions of the superior trunk’s arrangement can be abbreviated as SPA: suprascapular, posterior (division), anterior (division). With that arrangement, the local anesthetic placed at the suprascapular nerve’s origin is very likely to block nociception from other afferent nerves originating from the posterior division of the superior trunk (ie, axillary and subscapular nerves). It may also block the lateral pectoral nerve that arises from the anterior division of the superior trunk, the lateral cord, or the anterior division of the middle trunk. The SPA anatomical relationship near the suprascapular nerve origin may explain the anterior suprascapular block’s analgesic noninferiority to the more proximal interscalene block.

How I Do It: Anterior Suprascapular Nerve Block

Performing an anterior suprascapular block is not much different than a supraclavicular block. The suprascapular nerve is located usually 0.5–1 cm under the skin, making it easy to perform even in patients with a high body mass index, which is exactly the patient population that should avoid phrenic nerve palsy. The block uses a high-frequency linear transducer, and the major challenge is the close proximity of the clavicle which limits ultrasound transducer movement. If available, using a small-footprint linear array transducer (eg, 25 mm) can facilitate transducer movement with less interference from the clavicle. Position the patient in a sitting position, at least 45 degrees with the head up, which helps displace the clavicle caudally (see Figure 1).11

Figure 1: Anterior suprascapular block: patient, transducer, and needle position

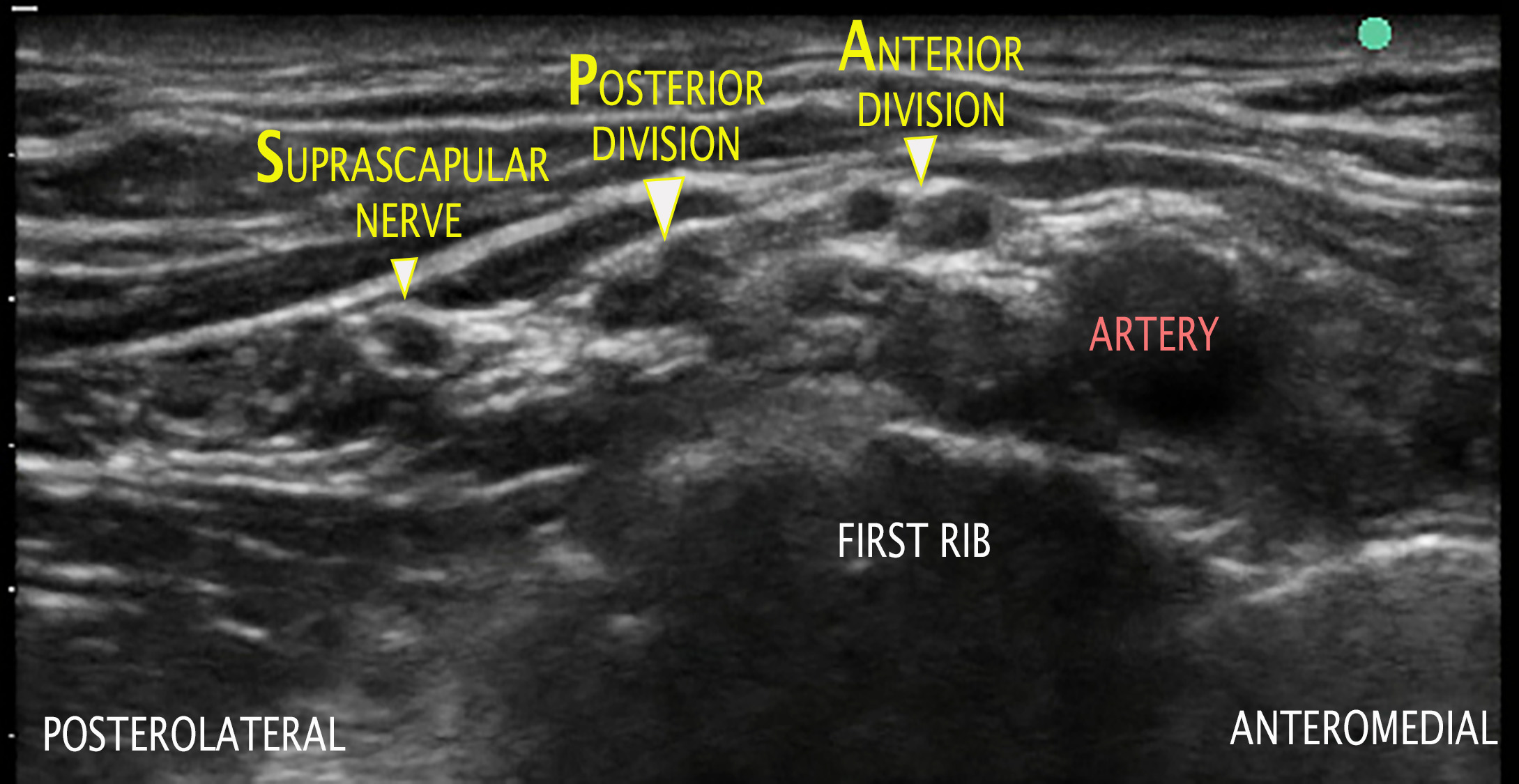

Place the transducer in the supraclavicular fossa, which obtains a standard supraclavicular view with the subclavian artery medial and the brachial plexus posterolateral. From the standard supraclavicular view, the suprascapular nerve is located at the most lateral and posterior part of the brachial plexus. Translate the transducer laterally, toward the ipsilateral shoulder, following the suprascapular nerve. As the plexus is imaged more laterally, the suprascapular nerve will separate from the brachial plexus. At this point, visualize the SPA arrangement of the nerves from lateral to medial: suprascapular, posterior (division of the superior trunk), anterior (division of the superior trunk) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Anterior suprascapular block: SPA arrangement of the superior trunk’s suprascapular nerve, posterior division, and anterior division from lateral to medial

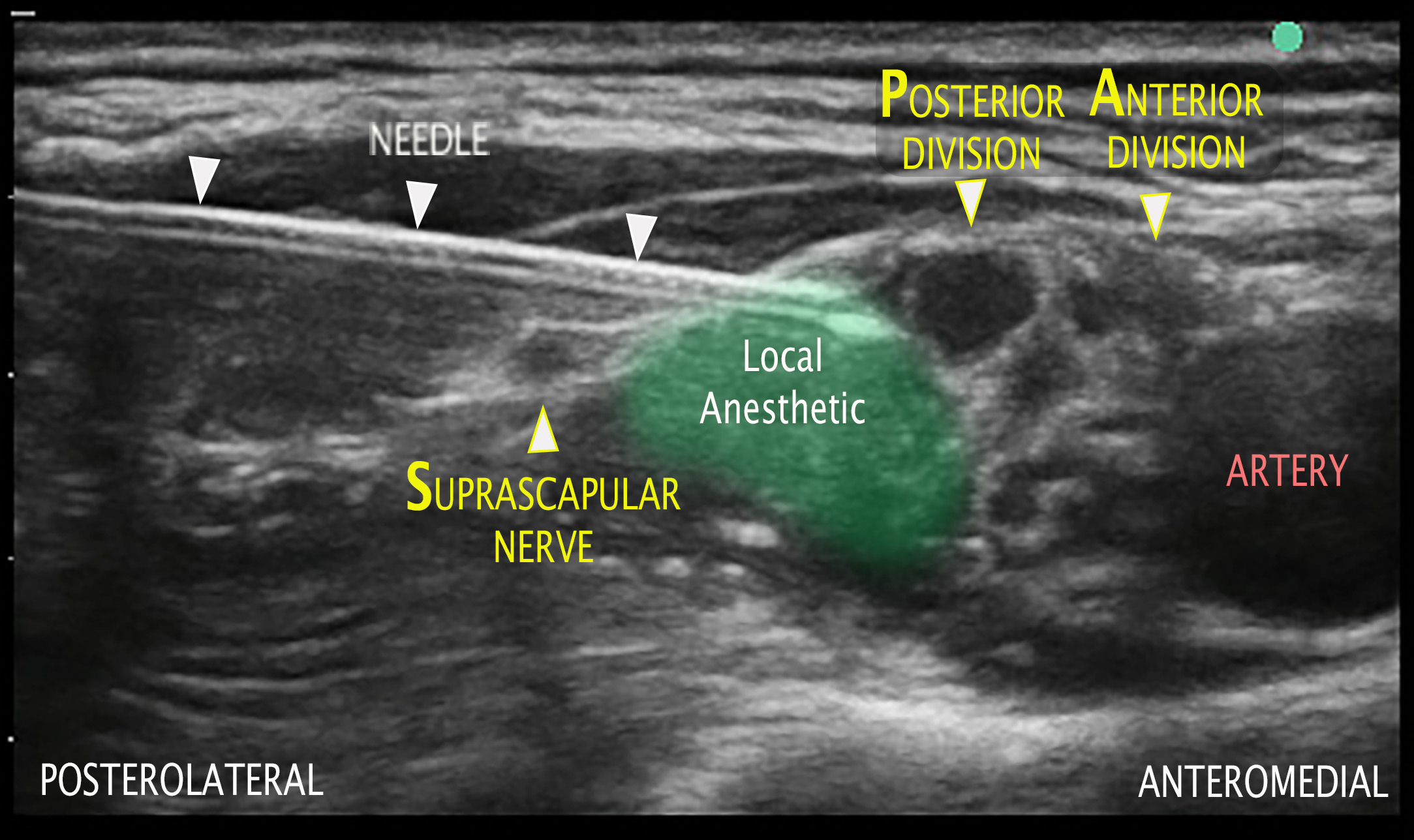

Once the nerve is located, deposit 5–15 mL of local anesthetic near the suprascapular nerve. Advance the needle similarly to a supraclavicular block, starting posterolateral and aiming anteromedial (see Video 1). Visualize the local anesthetic spread around the suprascapular nerve with some spread toward the closest part of the brachial plexus, usually the posterior division of the superior trunk (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Anterior suprascapular block: needle and local anesthetic placement between the suprascapular nerve and posterior division of the superior trunk

With the anterior approach to the suprascapular nerve, phrenic nerve palsy may occur, yet its likelihood is significantly reduced compared to an interscalene block.3 Use of lower-volume doses or more dilute local anesthetic agents further reduce the incidence. Peripheral nerve catheters may also be placed at the anterior approach location with improved respiratory mechanics demonstrated at 24 hours.12

In conclusion, the anterior suprascapular block based on the SPA anatomy is a powerful tool to provide postoperative shoulder analgesia by single injection or continuous nerve block while minimizing ipsilateral phrenic nerve paralysis.

David B. Auyong, MD, is the medical director at Lindeman Ambulatory Surgery Center and section head for orthopedic anesthesia at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, Washington.

References

- Price DJ. The shoulder block: a new alternative to interscalene brachial plexus blockade for the control of postoperative shoulder pain. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:575–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057x0703500418

- Hartel F, Keppler W. Erfahrungen uber die kulenkampff’sche anasthesie des plexus brachialis unter besonderer berucksichtung neben-und nacherscheinungen. Arch F Kiln Chir. 1913;103:1–43.

- Tran D, Elgueta M, Aliste J, Finlayson R. Diaphragm-sparing nerve blocks for shoulder surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(1):32–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000529

- Auyong DB, Hanson NA, Joseph RS, et al. Comparison of anterior suprascapular, supraclavicular, and interscalene nerve block approaches for major outpatient arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(1):47–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000002208

- Aszmann OC, Dellon AL, Birely BT, McFarland EG. Innervation of the human shoulder joint and its implications for surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;330:202–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199609000-00027

- Laumonerie P, Dalmas Y, Tibbo ME, et al. Sensory innervation of the human shoulder joint: the three bridges to break. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(12):e499–e507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.07.017

- Neal JM, Gerancher JC, Hebl JR, Ilfeld BM, McCartney CJ, Franco CD, Hogan QH. Upper extremity regional anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding, 2008. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009; 34:134-70. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819624eb

- Laumonerie P, Dalmas Y, Tibbo M, Robert S, Faruch M, Chaynes P, Bonnevialle N, Mansat P. Sensory innvervation of the human shoulder joint: the three bridges to break. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020 Dec; 29(12): e499-e507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.07.017

- Hanna A. The SPA arrangement of the branches of the upper trunk of the brachial plexus: a correction of a longstanding misconception and a new diagram of the brachial plexus. J Neurosurg. 2016;125(2):350–4. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.5.jns15367

- Porzionato A, Macchi V, Stecco C. Surgical anatomy of the pectoral nerves and the pectoral musculature. Clin Anat. 2012;25(5):559–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.21301

- Grant SA, Auyong DB. Ultrasound Guided Regional Anesthesia. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017. https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780190231804.001.0001/med-9780190231804

- Auyong DB, Yuan SC, Choi DS, et al. A double-blind randomized comparison of continuous interscalene, supraclavicular, and suprascapular blocks for total shoulder arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(3):302–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/aap.0000000000000578

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top