Informed Consent and the Postoperative Pain Control Conundrum

Consider the following scenario: A surgeon requests an epidural for a patient who underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy that has converted to open. The patient has a history of opioid dependence and is currently on methadone maintenance as an outpatient. In the recovery room, the patient is reporting 10/10 pain. Intravenous opioids and attempts at multimodal analgesia provide minimal relief. Unfortunately, consent for regional anesthesia was not obtained by your colleague prior to general anesthesia for surgery. Would you consider this patient able to consent for a regional block? Are you comfortable placing an epidural in this patient? What about an abdominal wall block? Some anesthesiologists may lean toward intervening in the attempt to “do the right thing,” but others might fear legal consequences and refuse to perform any interventional procedure. Do you discuss the risks and benefits of opioids as the alternative to a regional technique?

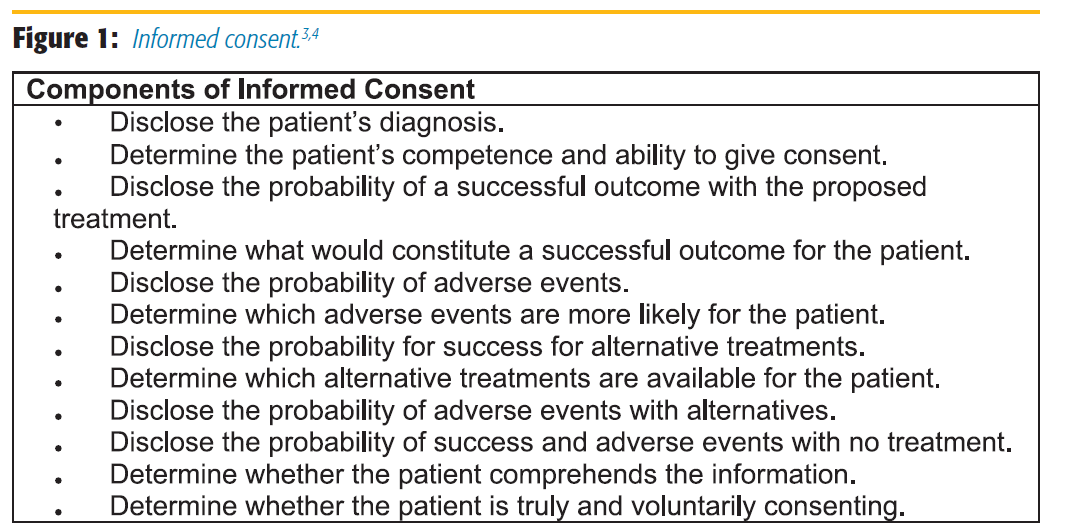

Informed consent has long been criticized as being merely a tool to avoid physician liability. However, informed consent is in the intersection point between a physician’s obligation to protect a patient’s health through beneficence and a physician’s obligation to respect patient autonomy (Figure 1).1 We no longer live in “the good old days” when the physician made decisions based on what he or she thought was in the patient’s best interest. The foundation of informed consent lies within the principle of autonomy, and we have no choice but to place it at the forefront of patient care. The process of obtaining informed consent must respect patient autonomy, ensure adequate decision-making capacity, and provide necessary information. All of the above should take place while practicing in the best interest of the patient.

Informed consent has long been criticized as being merely a tool to avoid physician liability. However, informed consent is in the intersection point between a physician’s obligation to protect a patient’s health through beneficence and a physician’s obligation to respect patient autonomy (Figure 1).1 We no longer live in “the good old days” when the physician made decisions based on what he or she thought was in the patient’s best interest. The foundation of informed consent lies within the principle of autonomy, and we have no choice but to place it at the forefront of patient care. The process of obtaining informed consent must respect patient autonomy, ensure adequate decision-making capacity, and provide necessary information. All of the above should take place while practicing in the best interest of the patient.

In health care, informed consent has been described as a process by which patients learn the purpose, benefits, and risks of a treatment or intervention as well as alternatives to the proposed treatment and voluntarily agrees to undergo the procedure. Typically, this has been formalized by a signature or attestation to confirm the patient’s understanding. In an ideal world, informed consent would occur prior to a scheduled surgery or procedure, without stress or duress. Delivery of appropriate information at an adequate literacy level should be provided free from time constraints. Patients would be allowed time to review the information and formulate questions and concerns and then be given the opportunity for follow-up and to express a decision or choice.

Anesthesiologists are uniquely subject to many vulnerabilities and challenges specifically related to informed consent. They often meet complex patients on the day of surgery and sometimes minutes prior to proceeding to the operating room. Patients are anxious, and the anesthesiologist can be the victim of production pressure. It is rarely a decision of treat or not treat in the preoperative setting. In this short amount of time, it is difficult to tease out patients’ concerns, priorities, and cultural preferences. Family dynamics are often at play and challenging to discern. Documentation can also be an issue, with poorly written notes, often lacking details and sometimes with ineligible handwriting, or reliance on a generic surgical consent that doesn’t discuss specific anesthesia risks. Lastly, anesthesiologists are often placed in situations in which informed consent has been obtained by others, such as when assuming care for a patient already anesthetized or being asked to provide regional anesthesia in the recovery room. Providers in this situation have never met the patient and are unaware of any patient concerns or preferences or what exactly was talked about in the preoperative period when consent was obtained.

Specifically, in the case referenced above, one is faced with a decision to treat pain by performing a skilled procedure on a patient when the ability of that patient to consent becomes clouded by the presence of duress and polypharmacy. In this situation, the question must be asked, “Is this patient able to make a medical decision under these circumstances?” Determining if a patient has decision-making capacity is the responsibility of the treating physician. There are several tools available to help guide an assessment, such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool (Mac-CAT). However, none of these tools have been validated in patients who have undergone anesthesia. For complex patients with mental illness or dementia, it may be appropriate to consider a formal psychiatric evaluation.2 While there are no formal guidelines on how to conduct a capacity assessment, it has been recommended the following four components be evaluated:3

- Understanding: The patient needs to have an understanding of his or her own condition.

- Appreciation: The patient must be able to appreciate the nature and significance of the decision he or she is about to make.

- Reason: The patient must be able to reason, weighing the risks and benefits of a procedure.

- Express: The patient must be able to communicate a choice.

These requirements of decision-making capacity can easily be remembered by the acronym “U ARE.” If a physician is unsure whether the patient has decision-making capacity, the next option would be a surrogate decision maker. It is often reasonable to seek and subsequently document the agreement of a surrogate decision maker with the expectation that the surrogate will attempt to determine what the patient would have wanted or would want in the current situation. When determining who should act as surrogate decision maker, it is important to know your state statutes and hospital policy, as this varies from state to state.4

With respect to informed consent, historically, there are two standards by which the law has defined our responsibility: the professional practice standard and the reasonable patient standard. In states that uphold the reasonable patient standard, physicians have incurred greater exposure to liability. Additionally, cases with similar facts may be decided differently based on the state in which they are tried, and a discrepancy between customary medical practice or professional standard and the patients’ expectations about risk disclosure may exist.5 Unfortunately, the varying legal climates across the United States and worldwide have serious implications on the way in which one conducts his or her clinical practice. It is therefore important to be aware of the standard upheld by your state.

The question now becomes: how do we bridge the ideal world to the real world when it comes to informed consent? As a profession, it is imperative to think about the entire perioperative period; hence, the birth of the perioperative surgical home. This approach encourages a discussion with patients about various types of anesthesia, including postoperative pain control, which would be free of any duress or time constraints. In addition, it is vital to continually reach across the drapes to our surgical colleagues, provide educational materials and updates on various anesthetic techniques or pain management options, and offer consultation on high risk patients (ie, opioid dependence) to get ahead of the potentially challenging cases.

“Anesthesiologists are uniquely subject to many vulnerabilities and challenges specifically related to informed consent.”

Recently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) approved patient decision aids for epidural and spinal anesthesia as well as peripheral nerve blocks.6 These aids are available for all ASA members to incorporate into their practice. They are written at an appropriate literacy level and provide unbiased information on risks and benefits of the procedures. Within the regional community, it has been shown that risk disclosure for regional anesthesia varies amongst practitioners.7 Therefore, it may benefit both physicians and patients to develop a consensus for consent practices with guidelines regarding risk disclosure for specific blocks or procedures. Another consideration is the actual consent form. Depending on your institution, if a generic surgical consent does not discuss the risks adequately, it may be prudent to develop a separate consent for both general and regional anesthesia.

In summary, informed consent is a crucial part of patient care from both ethical and legal standpoints. It is therefore important to know state statutes and policies of your home institution. It is crucial to document your assessment of patient capacity and your consent process. Ultimately, spending adequate time with your patients, treating them sensitively and compassionately, and allowing them to take part in the decision-making process will lead to improved satisfaction for both parties as well as improved outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press;2009.

- Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834–1840.

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patient’s capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1998;25:1635–1638.

- DeMartino ES, Dudzinski DM, Doyle CK, et al. Who decides when a patient can’t? Statutes on alternate decision makers. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1478–1482.

- Studdert, D, Mello M, Levy M, et al. Geographic variation in informed consent law: two standards for disclosure of treatment risks. J Empir Leg Stud. 2007;4(1):103–124.

- Domino KB, Posner KL, Sween LK, Shapiro FE. Improving patient-centered care delivery in 2017: introducing pre-anesthesia decision aids. ASA Newsletter. 2017;81(5):10–13.

- Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, et al. Disclosure of risks associated with regional anesthesia: a survey of academic regional anesthesiologists. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(1):7–11.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top