Neuromuscular Ultrasound: An Overview and Clinical Interpretation for Pain Physicians

Cite as: Meiling JB, Luetmer MT, Boon AJ. Neuromuscular ultrasound: an overview and clinical interpretation for pain physicians. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2025;50. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020125.013.

Introduction

Since its first use in the mid-20th century, the clinical application of ultrasound has expanded for interventional and diagnostic purposes.1 As the technology has evolved, physiatrists and neurologists have started incorporating diagnostic ultrasound, commonly referred to as neuromuscular ultrasound (NMUS), into clinical practice with electrodiagnostic (EDX) examination.2 The focus of NMUS is to visualize nerve and muscle tissue. In combination with nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG), NMUS aids in diagnosing peripheral nerve and muscle disorders.2

While it’s not included in formal training within pain medicine fellowship programs, understanding the benefits of NMUS application within an EDX examination is vital for pain physicians to understand better the disease processes affecting their patients. We aim to provide a brief overview of the use of NMUS in several categories of nerve and muscle disorders to assist in the clinical interpretation of these sonographic and EDX findings for pain medicine physicians.

A Brief Review of NMUS in Healthy Nerve and Muscle

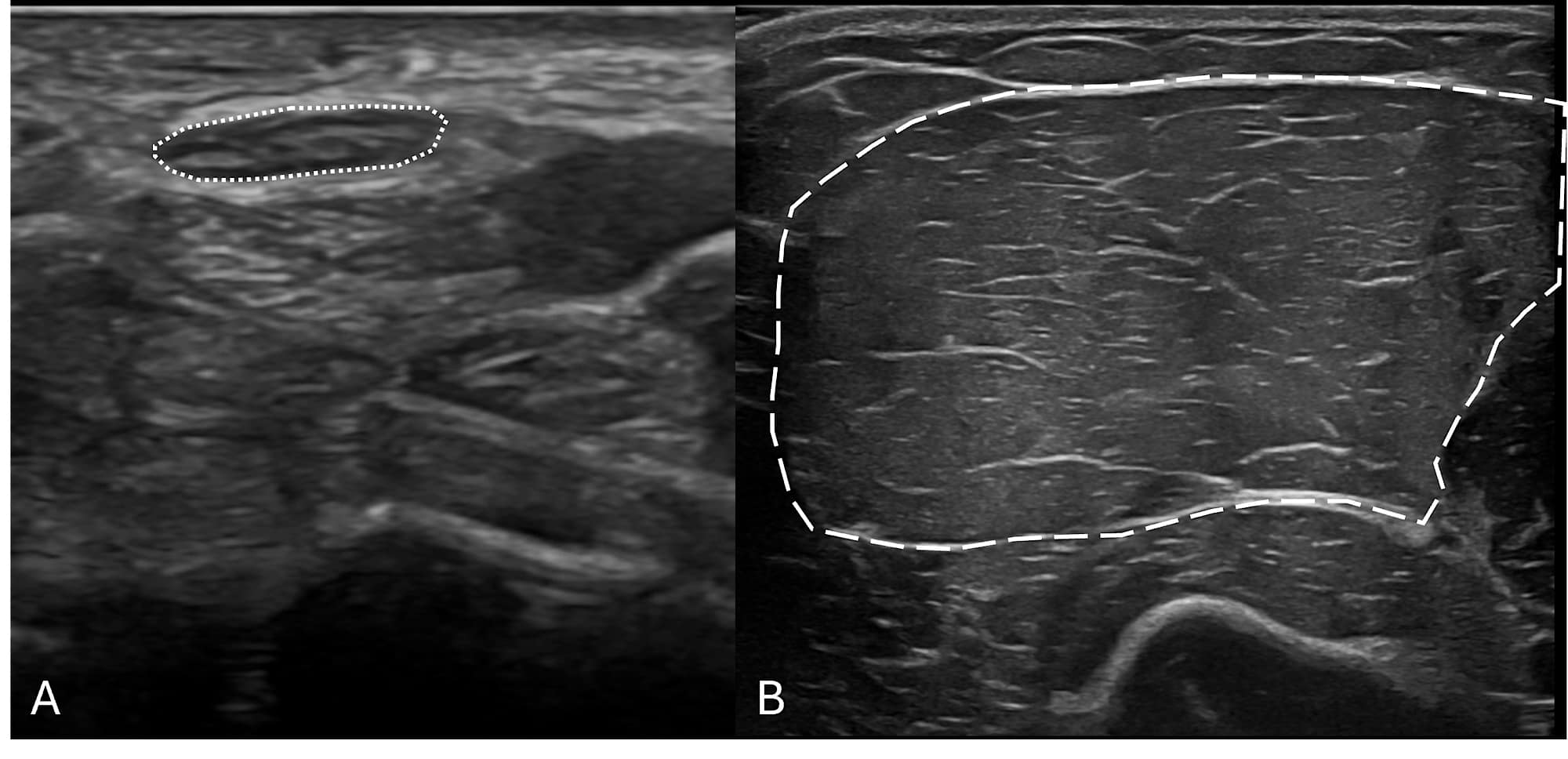

Before one can identify pathologic changes in peripheral nerves and muscles with NMUS, it is important to recognize the normal appearance of these structures. The normal structure of nerves and muscles is illustrated in Figure 1.

An Overview of NMUS in Several Disease Categories

Mononeuropathies

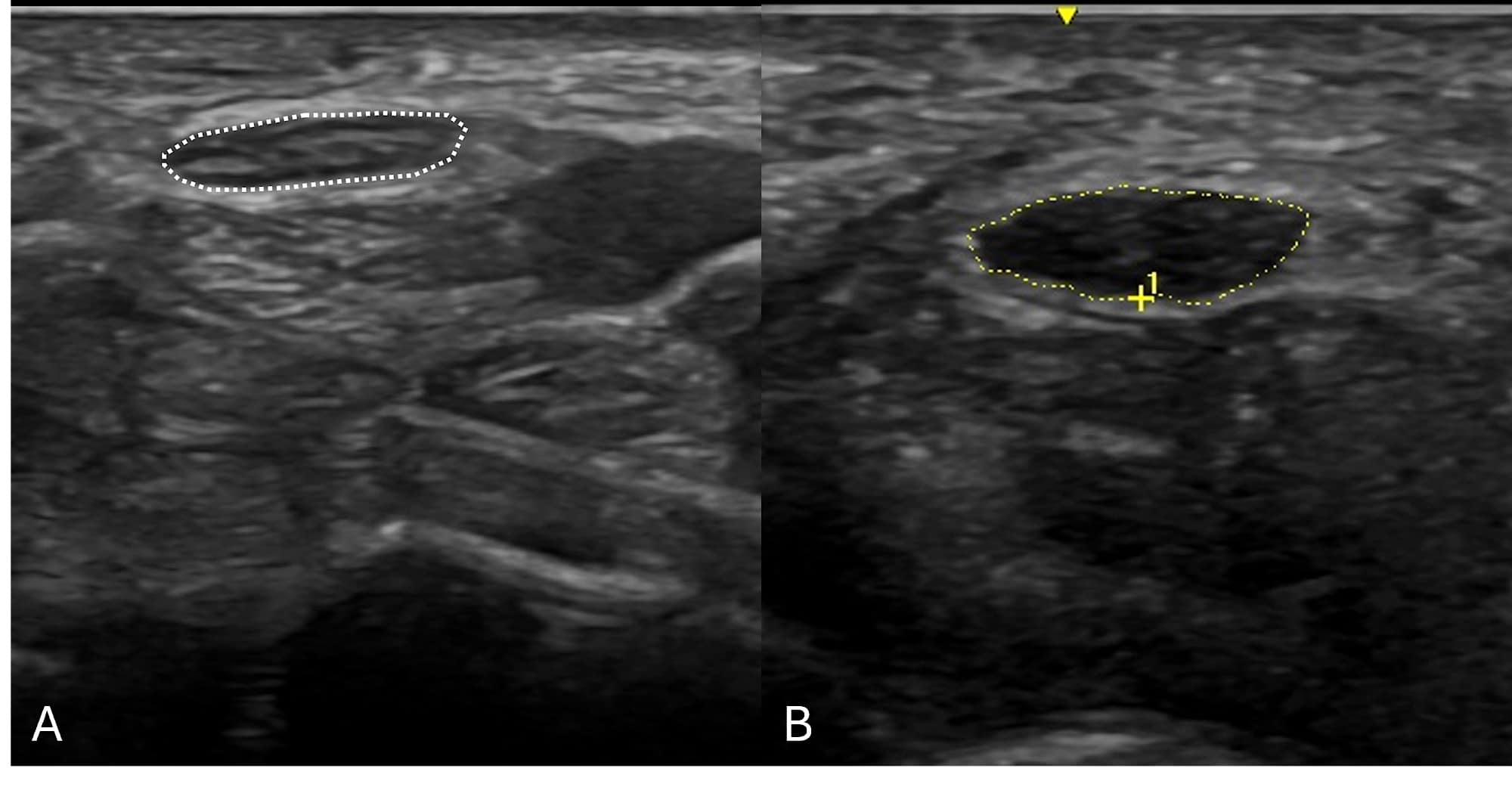

Mononeuropathies usually present as focal pain, sensory disturbance, or weakness limited to a single peripheral nerve distribution. The most widely used application of NMUS is in mononeuropathies, especially median neuropathy at the wrist, ulnar neuropathy, and fibular (peroneal) neuropathy. NMUS of mononeuropathies can identify both structural changes of the affected nerve and the underlying etiology of that nerve injury.3 Increased cross-sectional area is the most reliable finding on ultrasound and in cases of entrapment, such as median neuropathy at the wrist (better known as carpal tunnel syndrome), as seen in Figure 2. This is particularly advantageous in cases of mononeuropathies that are “non-localizable” based on NCS and EMG, which occur frequently in ulnar neuropathy and mild median neuropathy at the wrist.4-6

Causes of entrapment, such as ganglion cysts, tenosynovitis, AV fistulas, and hypertrophic accessory muscles, may be identified by sonographic examination.3 NMUS should be strongly considered in patients presenting with foot drop and EDX-proven fibular neuropathy to exclude intraneural ganglion cysts within the fibular nerve, which are treatable and can lead to irreversible foot drop if missed.7

In cases of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries, NMUS may identify foreign bodies (ie, bullet fragments, wood splinters, metal shards, etc.), confirm the presence of nerve continuity, discover post-traumatic neuroma-in-continuity, and in cases of transection, localize the two separated nerve ends.8 Besides entrapment and trauma, mononeuropathies rarely can be caused by nerve tumors (such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, and lipofibromatous hamartomas), which can be identified on NMUS as mimickers of classic nerve entrapments found on EDX studies3 as long as the view is not limited by penetration of the ultrasound beam due to body habitus or overlying bone. It is important to note that while NMUS can identify structural changes and potential etiologies, NMUS has not been able to assess the severity of nerve injuries except in the case of complete nerve transection. NCS and EMG are the gold standard for diagnosing the severity of injury.

Polyneuropathies

Like mononeuropathies, polyneuropathies – pathology involving multiple peripheral nerves – can present with positive symptoms (pain and dysesthesias) in addition to numbness and/or weakness. Although NMUS can help detect patterns of muscle denervation, NMUS has not yet been proven useful in axonal predominant polyneuropathies, such as diabetic and chemotherapy-induced polyneuropathies.9 However, NMUS can help confirm demyelinating polyneuropathies diagnosed on EDX. These polyneuropathies can be either acquired (eg, Guillain-Barré syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, multifocal motor neuropathy, POEMS syndrome) or hereditary (eg, Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease or hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP)).

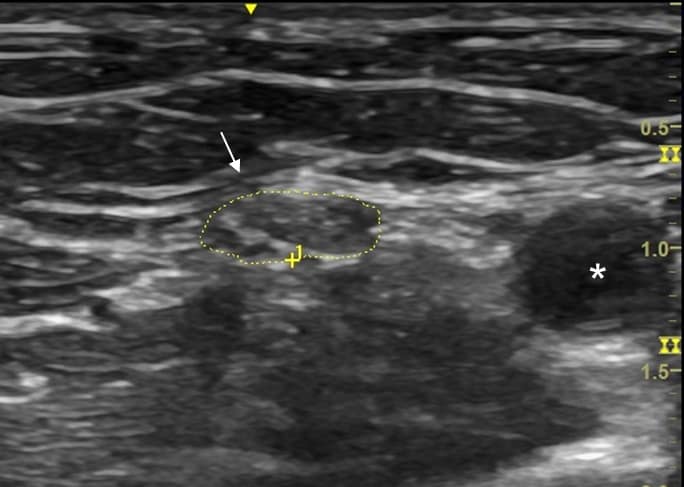

As a sonographic rule, acquired demyelinating polyneuropathies have single or multiple focal patchy areas of nerve enlargement throughout the course of multiple involved nerves, commonly at non-entrapment sites, and particularly in the proximal portions of upper limb nerves near the axilla and within the brachial plexus (Figure 3).9,10 In contrast, hereditary demyelinating polyneuropathies have either uniform enlargement throughout the entire course of the nerve, including the brachial plexus (CMT), or can have focal areas of nerve enlargement at common entrapment sites (HNPP).9,10 In some cases of a clinically suspected acquired demyelinating neuropathy, definitive conduction block is not evident in nerve conduction studies, or in severe polyneuropathy, responses can be absent. In these situations, the diagnosis may be arrived at based on NMUS findings (multifocal or uniform enlargement of peripheral nerves), thereby facilitating appropriate immune-modulating treatment.11,12

Brachial Plexopathies

Regional anesthesia and pain medicine physicians are familiar with ultrasound for needle guidance in regional blocks, such as a supraclavicular brachial plexus block. From a diagnostic perspective, NMUS of the brachial plexus is a more advanced sonographic technique that requires repeated practice and often side-to-side comparison, especially in the case of a unilateral disease process. A successful scan can be accomplished in three separate segments – the supraclavicular view for visualization of the nerve roots (C5-7, sometimes C8, and rarely T1), trunks (upper and middle, rarely lower), and divisions; the infraclavicular view for the cords, and axillary view for terminal nerve branches.13 NMUS of the brachial plexus is a helpful addition to EDX studies, particularly in traumatic brachial plexus injuries and demyelinating polyneuropathies.13,14 Focal, multifocal, or even diffuse enlargement of various portions of the brachial plexus can be visualized with NMUS.13,14 Edema, inflammation, and pseudo meningocele can be detected by advanced neuromuscular sonographers in cases of nerve root avulsion. This diagnosis is typically very painful and often predicts a poor functional outcome.15,16

While not technically an injury of the plexus itself, Parsonage-Turner syndrome (also known as neuralgic amyotrophy) is an acute-onset multifocal painful nerve injury involving multiple peripheral nerves.17 Structural changes identified on NMUS in Parsonage-Turner syndrome include fascicular enlargement, fascicular entwinement, and partial or complete constriction with nerve torsion (“hourglass constrictions”), which are visualized more often in the proximal portions of the median and radial nerves in the upper arm.18,19 These findings may predict a poor prognosis. Unlike brachial plexopathies, lumbar plexopathies cannot be visualized by NMUS due to limited penetration of the ultrasound beam and overlying bone.

Mononeuropathies usually present as focal pain, sensory disturbance, or weakness limited to a single peripheral nerve distribution. The most widely used application of NMUS is in mononeuropathies, especially median neuropathy at the wrist, ulnar neuropathy, and fibular (peroneal) neuropathy.

Motor Neuron Disease

Motor neuron disease (ALS) is a relatively common diagnosis encountered in the EDX lab and may initially be misdiagnosed as radiculopathy, particularly if a limited study is performed. NMUS can add diagnostic value in this setting by easily and painlessly identifying diffuse fasciculations in affected muscles, including cranial nerve innervated muscles and muscle architecture changes such as atrophy or a “moth-eaten” appearance of the denervated muscle.20

Muscle Disorders

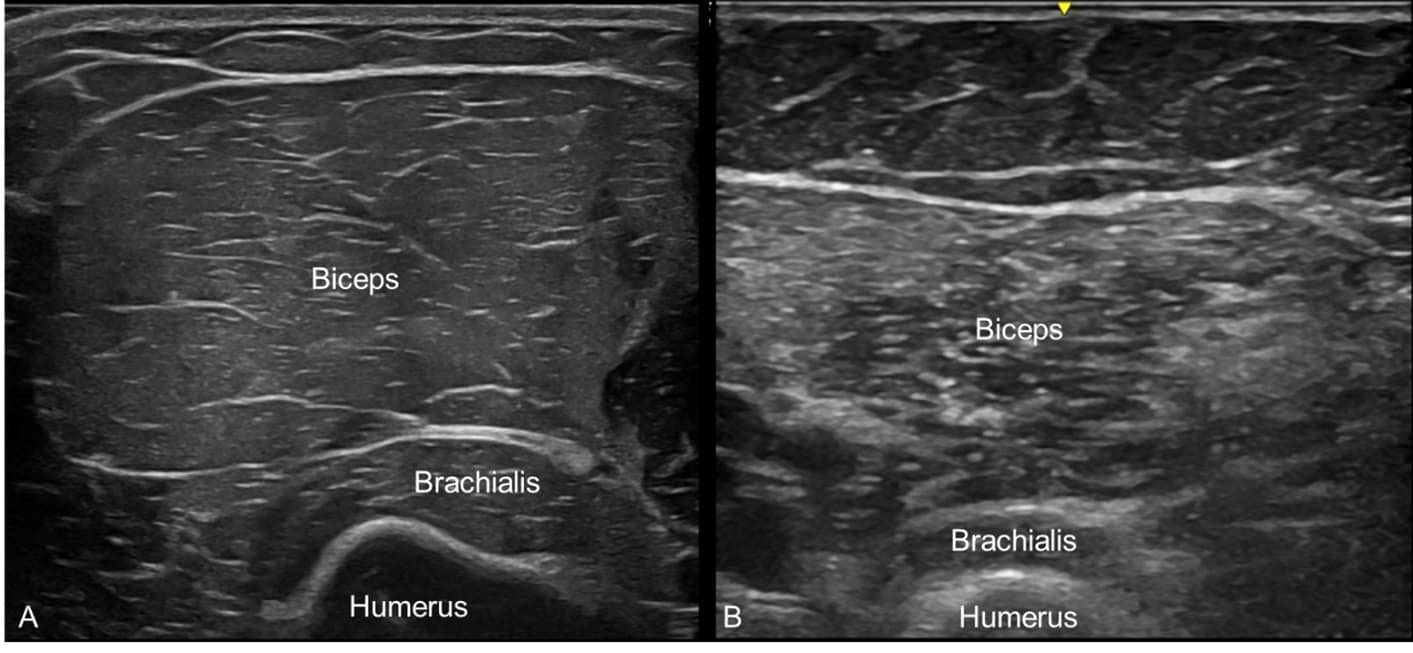

Disorders of muscle, including myopathies and muscular dystrophies, oftentimes have accompanying cramping and myalgia. These patients may be mislabeled with diagnoses such as fibromyalgia or myofascial pain syndrome. Structural muscle changes, such as muscle atrophy, loss of normal muscle architecture, and more diffusely increased echogenicity, can all be seen with NMUS (Figure 4).21

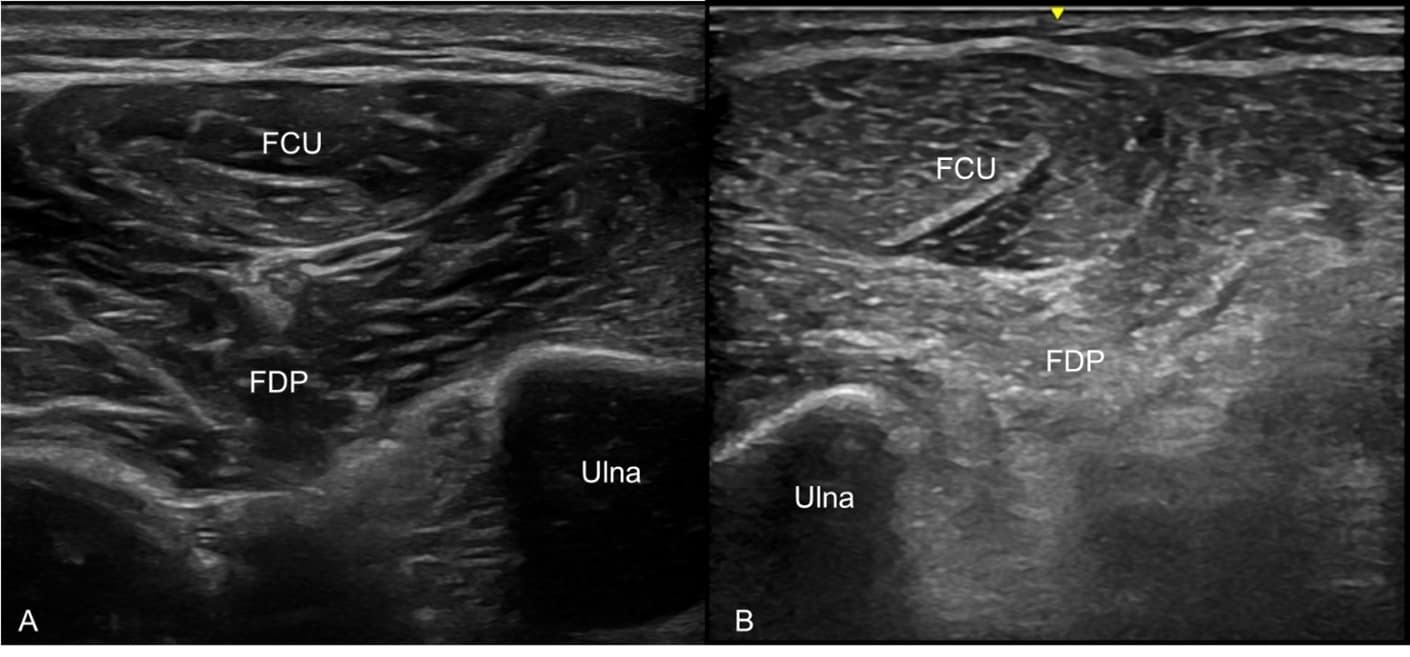

Some congenital and acquired myopathies have typical patterns of muscle involvement, where NMUS can help with diagnosis. For example, inclusion body myositis has a predilection for finger flexor and quadriceps muscles with frequent involvement of biceps brachii and tibialis anterior muscles. When placed at the window of the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus muscles, the image may demonstrate selective involvement of the finger flexors and a normal-appearing flexor carpi ulnaris (Figure 5).22 NMUS can also help guide the selection of an optimal muscle biopsy site by identifying muscles with moderate involvement without placing an EMG needle in the muscle.23 This is also more comfortable for the patient.

Figure 5. Linear-array high-frequency ultrasound transducer placed in a transverse view at the medial forearm with the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) muscles in view. (A) Normal, healthy FCU and FDP muscles

with good muscle bulk and normal muscle architecture. (B) Selectively involved FDP muscle with atrophy, increased echogenicity, and loss of normal muscle architecture adjacent to a normal-appearing FCU muscle in a case of inclusion body

myositis.

Conclusion

NMUS is a complementary tool to EDX examinations, facilitating a better understanding of nerve and muscle structural changes in acquired and hereditary neuromuscular conditions. Pain medicine physicians would benefit from understanding the potential added value of this additional resource when applied to the care of their patients.

References

- Nielsen MB, Søgaard SB, Bech Andersen S, et al. Highlights of the development in ultrasound during the last 70 years: a historical review. Acta Radiol 2021;62(11):1499-1514. https://doi.org/10.1177/02841851211050859

- Walker FO, Cartwright MS, Wiesler ER, et al. Ultrasound of nerve and muscle. Clin Neurophysiol 2004;115(3):495-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2003.10.022

- Cartwright MS, Hobson-Webb LD, Boon AJ, et al. Evidence-based guideline: neuromuscular ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2012;46(2):287-93. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23389

- Alrajeh M, Preston DC. Neuromuscular ultrasound in electrically non-localizable ulnar neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2018;58(5):655-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26291

- Aseem F, Williams JW, Walker FO, et al. Neuromuscular ultrasound in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome and normal nerve conduction studies. Muscle Nerve 2017;55(6):913-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25462

- Yoon JS, Walker FO, Cartwright MS. Ulnar neuropathy with normal electrodiagnosis and abnormal nerve ultrasound. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91(2):318-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.10.010

- Leijten FS, Arts WF, Puylaert JB. Ultrasound diagnosis of an intraneural ganglion cyst of the peroneal nerve. Case report. J Neurosurg 1992;76(3):538-40. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1992.76.3.0538

- Elshewi IE, Fatouh MM, Mohamed R, et al. Value of ultrasound assessment for traumatic nerve injury of the upper limb. J Ultrasound 2023;26(2):409-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-022-00756-2

- Nasr-Eldin YK, Cartwright MS, Hamed A, et al. Neuromuscular ultrasound in polyneuropathies. J Ultrasound Med 2024;43(7):1181-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.16447

- Goedee SH, Brekelmans GJ, van den Berg LH, et al. Distinctive patterns of sonographic nerve enlargement in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A and hereditary neuropathy with pressure palsies. Clin Neurophysiol 2015;126(7):1413-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2014.08.026

- Meiling JB, Penry VB. Diagnostic neuromuscular ultrasound to confirm clinical significance of a genetic variant for Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4C: a case report. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2024;103(10):e133-6; https://doi.org/10.1097/phm.0000000000002483

- Van den Bergh PYK, van Doorn PA, Hadden RDM, et al. European Academy of Neurology/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: report of a joint task force-second revision. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2021;26(3):242-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jns.12455

- Baute V, Strakowski JA, Reynolds JW, et al. Neuromuscular ultrasound of the brachial plexus: a standardized approach. Muscle Nerve 2018;58(5):618-24. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26144

- Goedee HS, Jongbloed BA, van Asseldonk JH, et al. A comparative study of brachial plexus sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy and multifocal motor neuropathy. Eur J Neurol 2017;24(10):1307-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13380

- Coraci D, Paolasso I, Doneddu PE, et al. High-resolution ultrasound may depict pseudomeningocele. Neurol Sci 2016;37(8):1369-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2545-6

- Miller NJ, Meiling JB, Caress JB, et al. Neuromuscular ultrasound in cervical nerve root avulsion. Ann Neurol 2024;95(6):1220-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.26924

- Meiling JB, Boon AJ, Niu Z, et al. Parsonage-Turner Syndrome and hereditary brachial plexus neuropathy. Mayo Clin Proc 2024;99(1):124-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.06.011

- ArÁnyi Z, Csillik A, DéVay K, et al. Ultrasonography in neuralgic amyotrophy: sensitivity, spectrum of findings, and clinical correlations. Muscle Nerve 2017;56(6):1054-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.25708

- Cignetti NE, Cox RS, Baute V, et al. A standardized ultrasound approach in neuralgic amyotrophy. Muscle Nerve 2023;67(1):3-11. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.27705

- Cartwright MS, Walker FO, Griffin LP, et al. Peripheral nerve and muscle ultrasound in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2011;44(3):346-51. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.22035

- Hannaford A, Vucic S, van Alfen N, et al. Muscle ultrasound in hereditary muscle disease. Neuromuscul Disord 2022;32(11-12):851-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2022.09.009

- Vu Q, Cartwright M. Neuromuscular ultrasound in the evaluation of inclusion body myositis. BMJ Case Rep 2016; 2016:bcr2016217440. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-217440

- Wijntjes J, van Alfen N. Muscle ultrasound: Present state and future opportunities. Muscle Nerve 2021;63(4):455-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.27081