Personal Experiences with COVID-19

Here, we present three varied perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic from across the globe.

“Intubation Across the Pond”: A View of COVID-19 from a National Health Service (NHS) Worker

My Chicago Experience with the COVID-19 Pandemic

In-situ Simulation Training for Staff Preparedness for COVID-19: Experience from Hong Kong

“Intubation Across the Pond”: A View of COVID-19 from a National Health Service (NHS) Worker

by Amit Pawa, BSc(Hons) MB BS(Hons) FRCA, EDRA, Consultant Anaesthetist, Regional Anaesthesia Lead, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London; President – Regional Anaesthesia-UK (RA-UK)

This article represents a couple of “firsts” for me: it is the first piece I have written for ASRA News as a foreign correspondent, and it is the first time that I have written a piece unrelated to regional anesthesia.

I should state at the outset that this piece reflects my personal thoughts and opinions and does not represent the views of my employer or of the wider NHS.

So, what was COVID-19 like across the pond?

The Setting

I work in a large central London teaching hospital that has one of its sites situated opposite the Palace of Westminster on the bank of the river Thames where the U.K. government meets.

As I reflect on the last eight weeks, I can sum up the key to our response in four words: communication, preparation, simulation and support.

Our anesthetic department consists of over 120 consultants (attendings), plus a separate critical care directorate of approximately 30 consultants. We are also fortunate to have an adjoining pediatric hospital, pediatric critical care unit, and associated consultant staff. Add to this our large workforce of trainee doctors across all departments and you can picture a pretty impressive army of physicians. Now - imagine the Herculean task that would involve changing the working and shift pattern of this army of physicians! I am extremely proud to say that the strategic team at my hospital pulled this off in the most impressive way and within an unimaginable time frame!

The Early Days

Being relatively social media-savvy, I was observing the impending wave of cases first from China and subsequently from Italian colleagues on Twitter. It was apparent however, that large cohorts of British society were not as nervous as I was regarding the impending COVID-19 pandemic. Despite calls to wash hands to the tune of “happy birthday,” not to touch one’s face, and to cough and sneeze as if you were “dabbing,” people did not appear to be concerned or perhaps they just didn’t want to know what was coming.

In small corners of the operating room (OR) and anesthetic department of my hospital, however, a huge effort to prepare and plan was under way. Meetings of a rapidly assembled COVID strategic planning team were taking place with nurses, managers, and clinicians from ORs, anesthesia, perioperative medicine, critical care, and emergency medicine. In the weeks that followed, plans were instituted to first reduce and then cease elective surgery and outpatient clinic activity. The main priority was to increase our intensive care bed capacity by a factor of 5 to nearly 300 beds if required. Various plans for redeployment of medical and nursing staff were discussed. It was clear from the outset that anesthetists were going to be key to this effort. We had the biggest number of skilled consultants and trainees within the hospital, capable of stepping up to the task and providing hands-on care to the tsunami of ventilated patients headed our way.

Self-Isolation

Just as hospital planning started to ramp up, the U.K. Prime Minister announced that a persistent cough or high temperature were symptoms that would necessitate 14 days of family self-isolation. My wife developed a persistent cough at about the same time (coupled with numerous B-lines discovered using my own handheld ultrasound).

The two weeks of self-isolation that followed were the most bizarre period of time. There was an impressive amount of information coming from my employers, social media, professional webinars, and the press. At times, this was a little overwhelming and anxiety-inducing. In addition to this, I took up a new role as teacher to two young children while my wife recovered and returned to work. I was not prepared for feeling the stress and frustration of not being able to work and help my colleagues while I was symptom-free. When I was eventually allowed to return, I felt a mixture relief and trepidation at what I would find.

Communication

The first change I noticed was the necessity for my department to disseminate and communicate effectively. The decision was made to use secure and encrypted instant messaging platforms to signpost individuals to key news, updates, and tasks. Sub-groups and “chats” were then set up for smaller groups. Where necessary, emails were sent and teleconferencing software was used to hold virtual meetings.

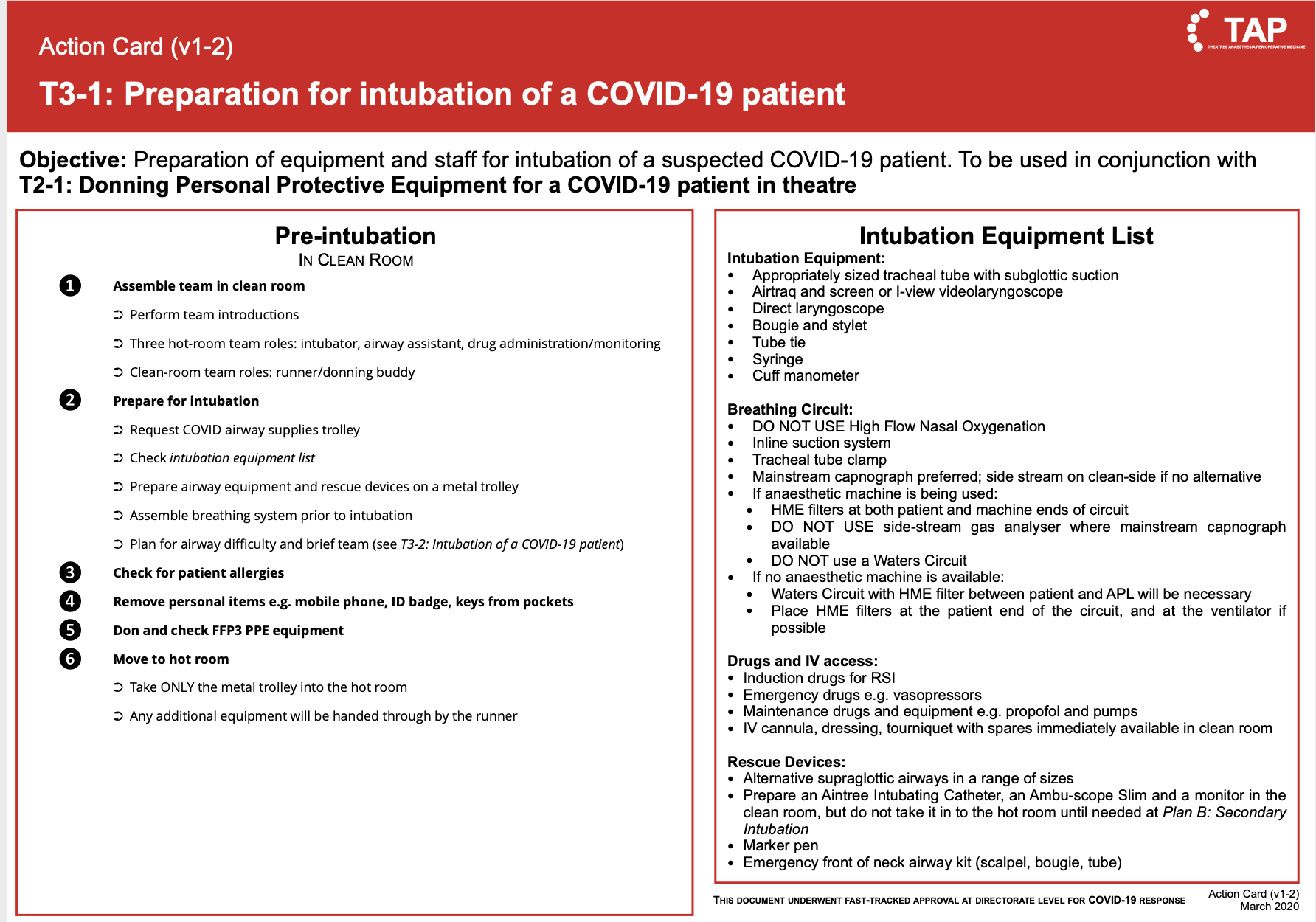

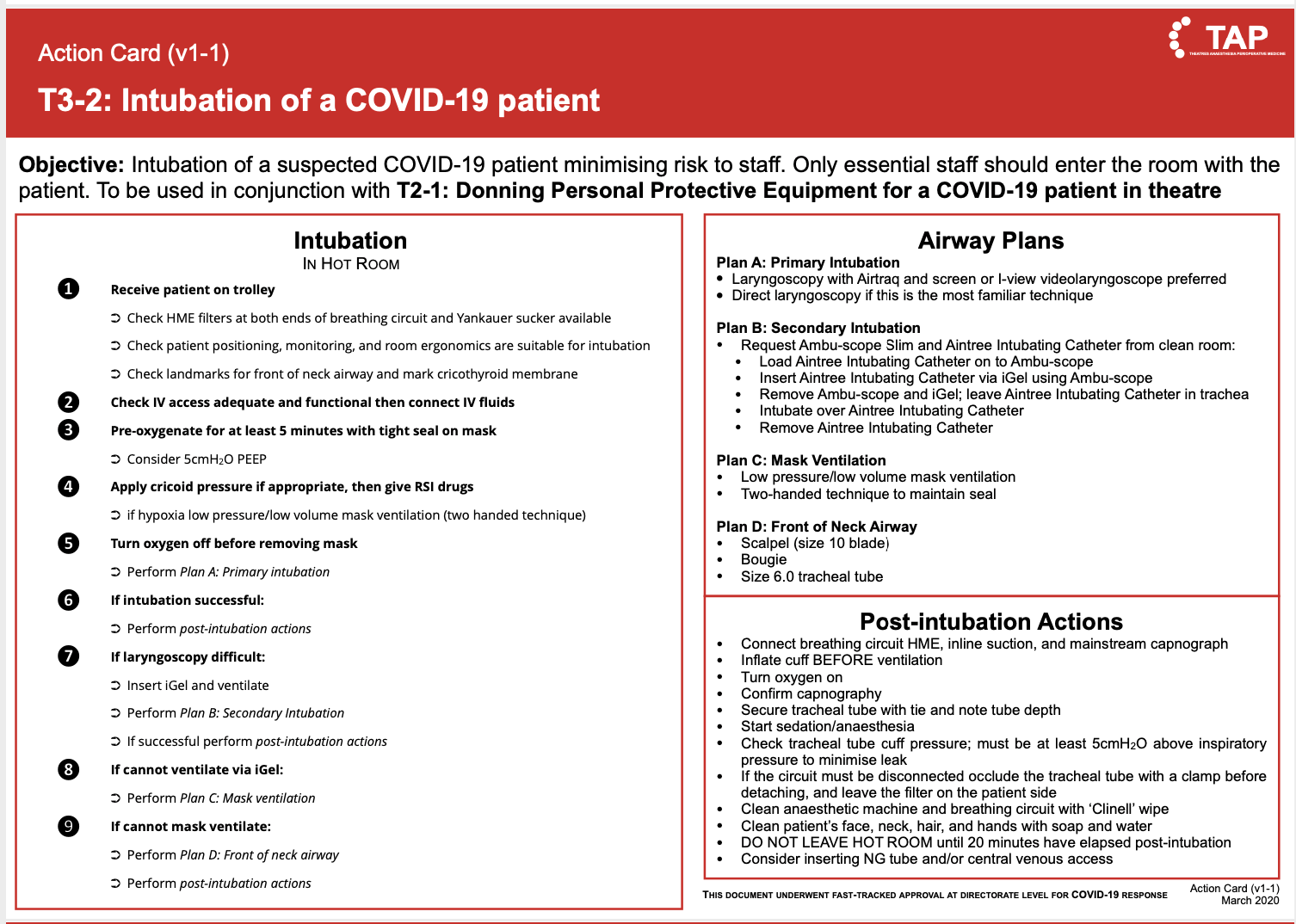

A New Vocabulary and Action Cards

We were introduced to the concepts of donning, doffing, and aerosol generating procedures (AGPs). A considerable amount of effort was taken to break down the steps of every existing and every new procedure we may encounter or perform in these new “COVID times.” These were formulated into a series of continuously evolving action cards, examples of which are shown below.

Thank you to authors Dr. Imran Ahmad, Dr. Paul Greig, and Dr. Stuart McCorkell for allowing us to share these action cards.

Simulation and Up-Skilling

Another key stage of preparation involved the use of simulation. No matter how many times you study how to don and then intubate an imaginary patient in personal protective equipment (PPE), it doesn’t prepare you for the real thing. Regular simulation was extremely useful in this regard.

Many of us would be redeployed to intensive care, and there was a need to up-skill and revise knowledge of this speciality from the distant past. Ro facilitate this, our intensive care colleagues ran a series of lectures covering the basics along with some COVID-19-specific issues, advanced ventilatory strategies, and lung ultrasound.

Teams

It was necessary to use personnel in the most safe and effective manner and to divide the burden of work that awaited us. To achieve this, our management formed teams to cover intensive care, emergency surgery, obstetrics, elective cancer and time-critical surgery, and COVID intubations. Other staff were additionally deployed to teams delivering education and training, PPE provision, communications, well-being, protocols and action cards, strategy, clinical governance, and research.

Intubation Teams

It was decided early on that the intubation of COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure would be performed solely by a Mobile Emergency Rapid Intubation Team (MERIT). MERIT was staffed solely by experienced consultants in order to ensure the highest level of expertise, and I volunteered to be part of it. Each MERIT consisted of two anesthetic consultants and two anesthetic assistants. Each time a page was received to intubate a patient, we collected intubation medications along with PPE and equipment bags and headed to the required location. The action card checklist ensured there was clarity and consistency in our approach.

In the early phases of the pandemic, up to 10-12 patients were being intubated over a 24-hour period, necessitating the delivery of a slick and efficient service. This was certainly aided by working with a consultant colleague (often the same person) who became your donning and doffing buddy, your emotional and moral support, and your back-up in the event of intubation difficulty.

The decision to intubate was made by the intensive care team, and patients were informed of this prior to our arrival. In many cases the “end of bed” appearance of the patient did not correlate with the severity of hypoxia or physiological derangement. This was compounded by the fact that many patients were settling their affairs or saying farewell to their loved-ones on the phone as we arrived. Scenes like these, in addition to those generated by the sheer number of patients crammed into intensive cares not designed to cater for their number, will color the landscape of my visual recollections from this period.

Despite the many positive outcomes of our interventions, there were a proportion of patients who did not survive their intensive care admission and who, sadly, died. I am sure there will be a significant psychological impact to all involved with caring for patients during this pandemic. This really emphasizes the need for the provision of support for us all in the months to come.

PPE

Evolving guidelines created much confusion in the U.K. regarding the type of PPE one should wear for different types and levels of care and in differing environments. There was also inconsistency in terms of what procedures were determined to be AGPs or not. Thankfully guidance from the anesthesia and intensive care perspective eventually came from reliable sources.[1, 2]

Within the U.K. as a whole, however, there were reports of shortages of PPE with some front-line care providers having to fashion their own or rely on donations from schools and private companies. The news was dominated by discussions and plans within government to address these shortages.

My personal experience with PPE provision was very different. The task of PPE sourcing, fit-testing, and provision for the whole directorate was addressed at the very early stages of the pandemic. We were extremely lucky and had access to a mix of single-use and reusable PPE, but the intubation teams were issued their own reusable masks and visors (Figure 1). This provision of high-quality PPE and the meticulous nature in which it was donned and doffed may well explain the low number of MERIT members who were symptomatic with COVID-19.

Figure 1. Image showing myself with my MERIT colleague in full PPE, including reusable face shield and respirator

Figure 1. Image showing myself with my MERIT colleague in full PPE, including reusable face shield and respirator

Well-Being

I was able to communicate personally with ASRA colleagues in New York at the early stages of the pandemic and was left in no doubt that tough times were ahead. Many members of the teams providing care for patients during this period will have seen, heard, and experienced events that will impact them for a long time.

In our department, we were reminded that we were not alone. We were encouraged to talk and acknowledge that “it’s ok not to be ok.” Generous donations of food, equipment, and gifts were received that certainly helped. A concerted effort was made to keep in close contact with our trainees and consultant colleagues who had often been thrust into new and challenging environments. Socially distanced “coffee and gas” gatherings were held twice a week.

We were also granted access to well-being resources from the major specialist bodies: Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Intensive Care Society, Association of Anaesthetists, and the Royal College of Anaesthetists.[3]

My personal strategy involved listening to sleep podcasts and relaxation applications (I would never have done this before) and the occasional attempt at writing poetry as a creative outlet. On my days off, family walks for the allotted once a day exercise also went some way to help me.

The Key to Success

I am well aware that my experience of COVID-19 will not reflect that of all practitioners or hospitals in the UK, but I can certainly claim with a sense of pride that the response in my hospital was as close as possible to the ideal. As I reflect on the last eight weeks, I can sum up the key to our response in four words: communication, preparation, simulation and support.

I sincerely hope that we don’t face something of this magnitude again – but if we do, I know that we will benefit from knowledge gained during this dreadful experience and have a game plan.

Many thanks to all my leaders, managers and colleagues who worked hard to prepare us in the most impressive of ways, but also a special thanks to my wife, Kathryn, and my MERIT buddy, Dr. Marcin Sicinski, for their support during this time. I could not have done it without them.

References

- Cook, T.M. (2020), Personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic – a narrative review. Anaesthesia. doi:1111/anae.15071

- Cook T, Harrop-Griffiths W. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for COVID-19 positive or possible patients. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e6613a1dc75b87df82b78e1/t/5e91ee25a89a10132534a96e/1586621990439/PPE-guidance2020_11.04.20.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2020.

- ICM Anaesthesia COVID-19. Wellbeing during COVID-19. Available at: https://icmanaesthesiacovid-19.org/wellbeing-during-covid-19. Accessed May 14, 2020.

My Chicago Experience with the COVID-19 Pandemic

by Rahul Guha, MD, Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology at the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago

To increase bed capacity amid the COVID-19 pandemic, scheduling for elective surgical cases at our medical center in Chicago, IL, was halted in mid-March. Because of the case load reduction, the volume of regional anesthesia procedures was greatly reduced. Nonetheless, regional anesthesia still proved invaluable for orthopedics cases, such as wrist or ankle fractures, as well as thoracic epidural catheters for large abdominal cases, such as colon resections and hysterectomies. As of mid-May, we have gradually restarted elective surgical cases, as per the guidelines set by our state.

We have created an airway service to cover all emergent intubations in the hospital.

Our institution maintains a supply of N95 and powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) masks that are available as needed in the care of our patients. However, PPE shortages necessitate reuse after appropriate disinfection, including usage following COVID-positive (COVID+) cases or patients under investigation (PUI). After doffing of the N95 masks, they are disinfected with ultraviolet light for one hour after contact with patients known or suspected to have COVID. This is done within our department using ultraviolet lamps. Recently, we also have started using ionized hydrogen peroxide for reprocessing of these masks; masks are placed in a plastic container and reprocessed at an outside location. PAPR masks are worn under surgical hoods during contact with patients to minimize the risk of contamination. Following use, they are cleaned with disinfectant wipes. For cases that are known to be COVID+ or PUI, most providers wear PAPR masks; otherwise N95 masks and face shield are used for asymptomatic patients.

Our hospital has implemented continuous masking and temperature screening for all staff and patients, as well as testing for coronavirus for all patients preoperatively. Patient testing is done within 72 hours prior to surgery whenever feasible because (at the time of this writing) 1-2 days are required to obtain results. Rapid testing is reserved for those unable to be tested prior to the day of surgery, with results generally available within an hour.

With the expanded volume of patients receiving care in our intensive care units (ICUs), there is a growing need for the placement of central venous and arterial vascular access. Along with experienced providers from other departments, our department has created a vascular access service. This service is dedicated to performing vascular access in the ICU in an effort to reduce the temporal burden of these procedures on our intensivist colleagues. Many of these procedures are performed in patients known to be COVID+, where full PPE with a N95 mask is donned prior to entering the patient’s room. For central line placement, an additional sterile gown and gloves are donned within the patient’s room.

Furthermore, we have created an airway service to cover all emergent intubations in the hospital. This service provides airway management for patients located in our ICUs, emergency room, and other areas where out-of-OR intubation may be required. An anesthesiologist carries a hospital-wide airway pager at all times, and a second anesthesia provider is available to assist with appropriate donning/doffing of PPE and during intubation. This team serves to make intubations as coherent and seamless as possible. The team structure is also invaluable should the airway becomes challenging to manage.

In-situ Simulation Training for Staff Preparedness for COVID-19: Experience from Hong Kong

by Albert Kam Ming Chan, MBBS, FHKCA, FANZCA, FHKAM (Anaesthesiology), Associate Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Prince of Wales Hospital Hong Kong, and Manoj Kumar Karmakar, MD, FRCA, DA (UK), FHKCA, FHKAM, Professor, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

In the current COVID-19 pandemic, the burden of the disease on healthcare workers is immense. As of May 30, in United States alone, 64,479 healthcare workers have been infected, among whom 309 have died[1]. Similar astounding numbers for healthcare worker infections have been reported worldwide. The impact of healthcare worker infection extends beyond the physical well-being and threat to life – it disproportionately increases the workload and stresses the capacity and morale of staff and hospitals to continue to provide care[2]. As with the SARS epidemic in 2003, the current pandemic potentially has negative psychological effects on healthcare workers.[3–6] On the one hand, availability and standard of PPE have been an attributing factor; on the other hand, lack of awareness of healthcare workers to take precautions and inadequate training in infection control measures have also contributed to infections.[7]

In-situ simulation-based training and process testing will undoubtedly build staff capacity for managing such a rapidly progressing and devastating pandemic.

The challenge of such a rapidly progressing pandemic is multidimensional. There is an imminent need for communities to build up the capacity of healthcare workers in infection control measures and empower them with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to practice safely in the current epidemic. Moreover, hospital workflow and processes have to be tested and implemented in preparation of an outbreak that will undoubtedly stress the system.

Simulation-based medical education plays a critical role in staff preparedness for infection control[8,9], and this has been demonstrated in previous epidemics.[10] It has also been utilized effectively in healthcare systems and process testing and improvement.[11,12] Particularly when the simulation is performed “in-situ” (ie, within the clinical areas where patient care will take place with authentic interprofessional healthcare teams[13]), staff becomes more engaged and processes can be rigorously tested.

The Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care at Prince of Wales Hospital is a tertiary teaching hospital affiliated with the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Staff working in the operating theater and ICU frequently perform high-risk aerosol-generating procedures, such as tracheal intubation, non-invasive ventilation, tracheostomy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and manual ventilation before intubation and bronchoscopy.[14] Faced with the need to build staff capacity and testing systems processes, we developed an in-situ simulation program to prepare staff for managing suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the operating theater and ICU and to test and refine infection control protocols and workflow.

The details and outcomes of simulation training in the ICU have previously been reported,[15] while the results from the operating theater setting are reported in a manuscript currently under review. The workflow of our in-situ simulation (Table 1) can be adopted for various institutions. In a span of seven days, a total of 62 simulation training sessions were carried out in the airborne infection isolation room (AIIR) in our department, with 51 sessions in the operating theater and 11 sessions in the ICU. A total of 249 staff were engaged in the training, involving anaesthesiologists, intensivists, nursing staff, and other supportive healthcare workers. Based on principles of Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice[16], the simulation scenarios were designed to focus on rapid acquisition of procedural and teamwork skills for infection control in AGPs (including donning and doffing of PPE and subsequent airway management for COVID-19 patients). Moreover, staff were asked to provide feedback on how the processes and workflow could be improved, and these were incorporated into subsequent iterations of the infection control processes and retested in the simulated setting. System improvements include cognitive aids for staff to improve donning and doffing of PPE, airway management checklists for high-risk patients, additional manpower and staff for support outside the AIIR and checking for infection control breaches, and designated “dirty” trolleys to dispose of used airway equipment.[15]

Table 1: Overview of elements for designing and running in-situ simulation for Covid-19 infection control in the operating theatre and intensive care unit

Needs Assessment |

|

Institutional Support |

|

Educational Design |

|

Scenario Design |

|

Resource Availability |

|

Develop Protocols for Training | Staff safety is also important, especially if there are concerns with cross-infection during training. Screen for fever, symptoms, and contact history, and enforce hygiene principles and social distancing throughout training where possible. |

Process Testing and Refinement | Throughout the simulations and subsequent debriefings, identify workflow and systems issues and provide feedback to the responsible parties for refinement; retest in the simulated setting before implementation. |

Our simulation program has greatly increased the self-perceived competence and confidence of staff, while refining the infection control processes, and facilitated subsequent management of suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases. Setting up such a simulation program bears its own challenges. Using the AIIR enhances fidelity and authenticity and allows systems testing. However, AIIR may be occupied for clinical purposes, and balance between training needs and clinical service must be considered. Moreover, given the global shortage of supply, conservation of PPE is essential. Nonetheless, practicing infection control procedures such as donning and doffing is vital for staff safety;[17] therefore, efforts must be made to conserve PPE during training or substitutes should be considered. It is crucial to include all stakeholders while setting up such a simulation program, and the success in the program lies in institutional support to build capacity in a short amount of time.

In a critical time such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, in-situ simulation-based training and process testing will undoubtedly build staff capacity for managing such a rapidly progressing and devastating pandemic, and, it is hoped, will enhance the safety of frontline healthcare workers.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Cases in the U.S. Cases, Data, & Surveillance.

- Hong Kong Legislative Council. Report of the Select Committee to inquire into the handling of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome outbreak by the Government and the Hospital Authority. 2004.

- Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. Cmaj. 2003;168(10):1245-1251.

- Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924-1932. doi:10.3201/eid1212.060584

- Maunder RG. Was SARS a mental health catastrophe? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):316-317. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.004

- Chan-Yeung M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):421-427. doi:10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.421

- Zhou P, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Huang X, Fan X-G. Protecting Chinese healthcare workers while combating the 2019 novel coronavirus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(6):745-746.

- Sook S, Mi K. The Effects of Simulation-based Infection Control Training on the Intensive Care Unit Nurses ’ Perception , Clinical Performance , and Self-Efficacy of Infection Control. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2012;18(3):381-390.

- Luctkar-Flude M, Baker C, Hopkins-Rosseel D, et al. Development and evaluation of an interprofessional simulation-based learning module on infection control skills for prelicensure health professional students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2014;10(8):395-405. doi:10.1016/j.ecns.2014.03.003

- Phrampus PE, O’Donnell JM, Farkas D, et al. Rapid development and deployment of ebola readiness training across an academic health system the critical role of simulation education, consulting, and systems integration. Simul Healthc. 2016;11(2):82-88. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000137

- Reid J, Stone K, Huang L, S. Deutsch E. Simulation for Systems Integration in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2016;17(3):193-199. doi:10.1016/j.cpem.2016.05.006

- Dubé MM, Reid J, Kaba A, et al. PEARLS for Systems Integration: A Modified PEARLS Framework for Debriefing Systems-Focused Simulations. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(5):333-342. doi:10.1097/SIH.0000000000000381

- Patterson MD, Geis GL, Falcone RA, LeMaster T, Wears RL. In situ simulation: Detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(6):468-477. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000942

- World Health Organization. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected Interim guidance January 2020. 2020;(January):1-3.

- Choi GY, Wan WT, Chan AK, Tong S, Poon S, Joynt GM. Preparedness for COVID-19: using in-situ simulation to enhance infection control systems in the Intensive Care Unit. Br J Anaesth. 2020;Accepted f.

- Hunt EA, Duval-Arnould JM, Nelson-McMillan KL, et al. Pediatric resident resuscitation skills improve after “Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice” training. Resuscitation. 2014;85(7):945-951. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.02.025

- Lau JTF, Fung KS, Wong TW, et al. SARS Transmission among Hospital Workers in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):280-286. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030534

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top