How I Do It

Learn from your colleagues. ASRA Pain Medicine members share how they perform common procedures and accomplish other tasks.

- Listed by publication date, most recent on top

How I Do It: Distal Upper Extremity Ultrasound Guided Nerve Blocks

Cite as: Sehmbi H, Shah UJ, Uppal V. How I do it: distal upper extremity ultrasound guided nerve blocks. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2023;48. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110123.011.

All images are reproduced with permission from Dr. Herman Sehmbi.

Introduction

Ultrasound-guided brachial plexus blocks are the standard of care for many upper extremity procedures.1,2 However, a distal approach involving the peripheral nerves of the upper extremity (ie, radial, median, ulnar, and musculocutaneous nerves) may offer several benefits. It is possible to occasionally encounter sensory sparing of the hand from more proximal brachial plexus blocks that lead to block failure and consequent conversion to general anesthesia. Under such circumstances, the ability of an expert regional anesthesiologist to perform rescue blocks of distal nerves of the upper extremity can be beneficial. Blocking the individual nerves of the upper limb distally may be safer (away from critical structures of the neck/chest) and can allow less motor blockade (which may increase patient satisfaction) besides hastening block onset and consistency (when added to a brachial plexus block).3-6 However, surgical anesthesia may require blocking multiple distal nerves and restricting tourniquet use to below the elbow. Using a proximal tourniquet may preclude using distal blocks alone for surgical anesthesia without a proximal brachial plexus block. In this article, we review the technical aspects of performing the distal blocks of the upper extremity and highlight some of the clinical aspects of their usage.

Blocking the individual nerves of the upper limb distally may be safer and can allow less motor blockade.

Preparation

In our clinical practice, we perform ultrasound-guided blocks of distal nerves using a small footprint, high-frequency linear transducer (6-13 MHz) in a transverse plane, providing a cross-sectional view for all nerves. Essential components include a sterile probe cover with ultrasound gel, a hypodermic (25G) or a short bevel 22G block needle, sterile gloves, an assistant for positioning, local anesthetic injection, and sedation. After applying appropriate monitoring, supplemental oxygen, and established IV access, sedation generally consists of 2 mg of midazolam and 50-100 mcg of fentanyl. The administration is titrated to ensure patient comfort throughout the procedure. Aseptic technique is observed, and the ergonomics are considered such that the operator can comfortably visualize the ultrasound screen by looking straight ahead (ie, The operator stands at the head end, and the ultrasound machine is positioned in a direct line of sight on the ipsilateral or contralateral side.). Skin infiltration is provided via the administration of 1% lidocaine when using a short-bevel needle for the block but may not be needed if using a hypodermic needle.

Pertinent Anatomy

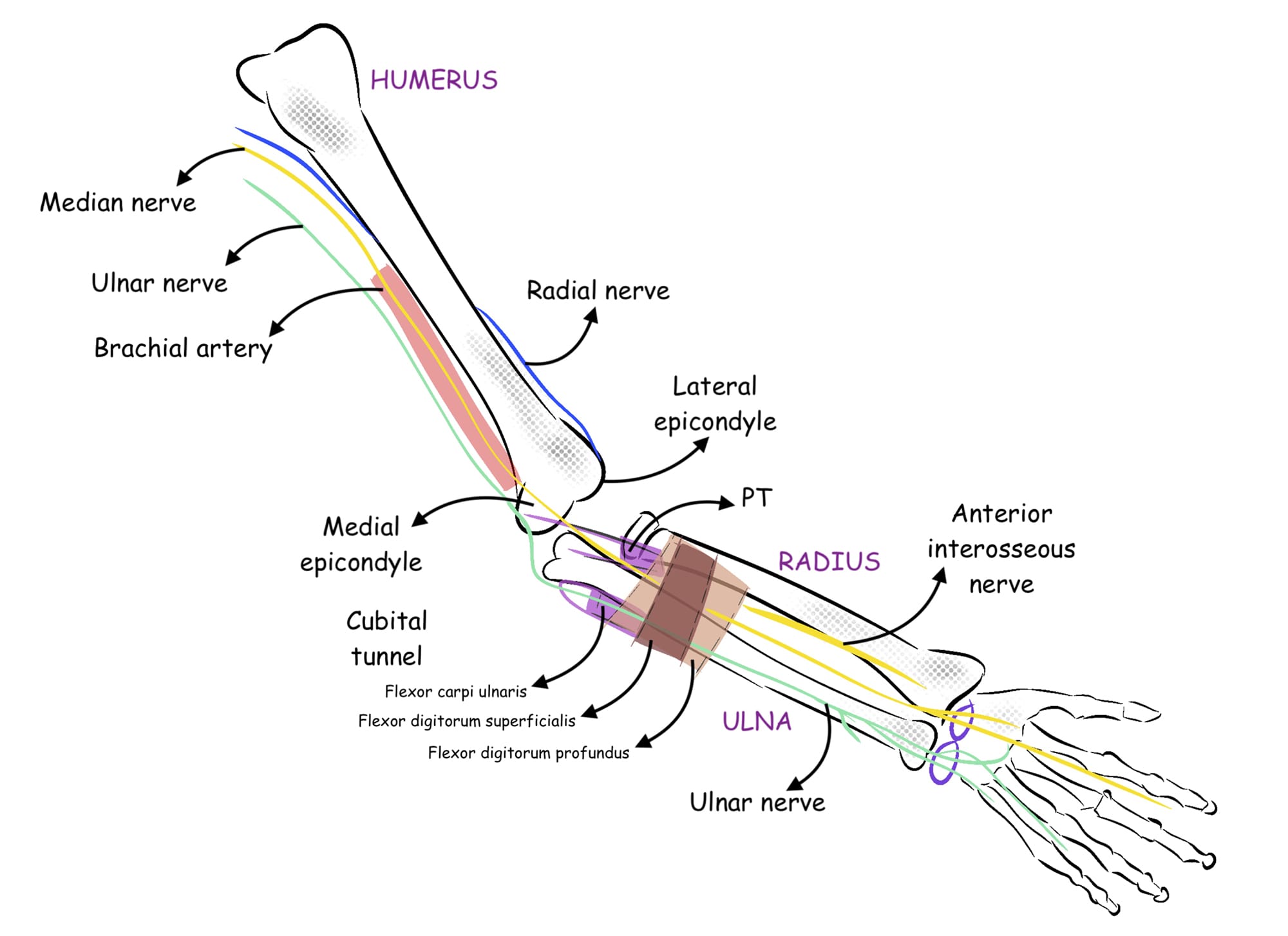

The upper limb is innervated mainly by four terminal branches of the brachial plexus, including the radial, median, ulnar, and musculocutaneous nerves (Figure 1). While other cutaneous nerves also innervate the arm (eg, the axillary nerve as well as the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and forearm), they are not considered here for brevity.

Procedure

The following section details the block performance of the four primary terminal nerves of the upper extremity. Clinical pearls are summarized at the end of the article.

Musculocutaneous Nerve: C5, C6, and C77,8

The musculocutaneous nerve, a branch of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus, pierces coracobrachialis to pass obliquely between the biceps brachii and the brachialis, innervating all three muscles and supplying the elbow joint. Next, it emerges on the lateral side of the arm, pierces the deep fascia lateral to the tendon of the biceps brachii, and continues into the forearm as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm. A schematic diagram is shown in Figure 2A. For a block, the patient is positioned supine with the arm blocked in an abducted position (Figure 2B). A linear transducer is used to identify the axillary artery in the axilla above the teres major muscle. The musculocutaneous nerve appears as a hyperechoic triangular or oval structure in the fascial plane between the coracobrachialis and biceps brachii muscles (Figure 2C). After raising a skin wheal using a local anesthetic, a 22G, 50 mm short bevel block needle is introduced in-plane in a lateral to a medial direction (or out-of-plane, depending on operator preference), aiming to enter the fascial plane next to the musculocutaneous nerve. If using a peripheral nerve stimulator (PNS), an evoked motor response constituting elbow flexion is obtained. After negative aspiration, 5 ml of local anesthetic is injected to encircle the nerve (Figure 2D).

Yellow Arrowhead = nerve, White Arrowhead = bone

Radial Nerve: C5, C6, C7, C8, and T17-9

The radial nerve originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus and enters the posterior compartment of the arm. The radial nerve then spirals obliquely around the humerus (spiral groove) and divides into the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and the main trunk.10 Next, the main trunk of the radial nerve pierces the lateral intermuscular septum to descend between the brachialis and brachioradialis. It divides into superficial and deep branches above the lateral epicondyle. The deep branch of the main trunk terminates as the posterior interosseous nerve. Figure 3A illustrates a schematic of its course and branches. It’s best to block the radial nerve before the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

For this part of the procedure, the arm is best placed with the shoulder adducted and internally rotated, and the elbow flexed so that it lies on the chest. This positioning allows the best access to the posterolateral aspect of the humerus (Figure 3B). A linear transducer is placed at the spiral groove to identify the humerus. Upon scanning distally, the radial nerve is usually seen as a triangular hyperechoic structure coming off the humerus (Figure 3C). After raising a skin wheal using a local anesthetic, a 22G, 50 mm short bevel block needle is introduced in-plane (or out-of-plane), aiming to enter the fascial plane next to the radial nerve. If using a PNS, an evoked motor response constituting thumb and finger extension is obtained. After negative aspiration, a local anesthetic injection of 5 ml is made circumferentially (Figure 3D).

Yellow Arrowhead = nerve, White Arrowhead= bone

Ulnar Nerve: C8, T17-9

The ulnar nerve originates from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and descends medial to the brachial artery to emerge behind the medial epicondyle. It enters the forearm’s anterior (flexor) compartment to lie between flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus. This relationship helps identify the nerve. Figure 4A illustrates a schematic of its course and branches. For a mid-forearm level block, the patient is positioned supine, and the arm supinated (Figure 4B). A linear transducer is placed just above the wrist, on its medial aspect, to identify the ulnar artery. Proximal scanning shows that the ulnar nerve is usually seen as an oval hyperechoic structure immediately medial to the artery (Figure 4C). After raising a skin wheal using a local anesthetic, a 22G, 50 mm short bevel block needle is introduced in-plane (or out-of-plane) to enter the fascial plane next to the ulnar nerve. If using a PNS, an evoked motor response constituting thumb adduction and ring finger flexion is obtained. An injection of 3-5 ml of local anesthetic is made after negative aspiration to cover the nerve circumferentially (Figure 4D).

Yellow Arrowhead= nerve, White Arrowhead= bone

Median Nerve: C5, C6, C7, C8, and T17-9

The median nerve is formed by the lateral root of the median nerve (from the lateral cord) and the medial root of the median nerve (from the medial cord) of the brachial plexus. It passes lateral to the brachial artery in the arm, crossing it anteriorly to lie medial to it just above the elbow joint. In the forearm, the median nerve passes between the two heads of pronator teres and then travels between flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus. Figure 5A illustrates a schematic representation of the course and median nerve branches. For a mid-forearm block, the patient’s arm is positioned extended and supinated (Figure 5B). A linear transducer is placed on the ventral aspect of the mid-forearm where the median nerve is visible in the fascial plane between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus (Figure 5C). A 22 G, 50 mm short bevel block needle is introduced in-plane (or out-of-plane) and aimed at the fascial plane next to the median nerve. If using a PNS, an evoked motor response constituting finger flexion is obtained. A 5 ml local anesthetic injection is made after negative aspiration to cover the nerve circumferentially (Figure 5D).

Yellow Arrowhead= nerve, White Arrowhead= bone

Anatomical Variability

Both cadaveric dissections and radiological assessments confirm that all upper limb nerves demonstrate considerable anatomical variations in their course, branching and innervation.11 The median nerve exhibits communicating branches with the musculocutaneous and ulnar nerves. Variations at the elbow and surrounding structures can lead to nerve compression. A bifid median nerve is found in about 15.4% of individuals, affecting the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Various anastomoses between the median nerve and other nerves, such as the Martin-Gruber, Riché-Cannieu, and Berrettini anastomoses, are present in the hand region resulting in diverse clinical presentations during neurological assessment and iatrogenic injury risks during surgical procedures. The musculocutaneous nerve may exhibit variation in its course (11% of cases) and communication with the median nerve.

Sometimes, the musculocutaneous nerve may be absent, and the median nerve takes over its functions. Although the ulnar nerve originates from C8 and T1, it can occasionally receive innervation from C7. Extensive anastomosis with branches of the median nerve in the forearm has clinical implications, such as failure of blocks. Understanding these variations is crucial for accurate clinical assessment, surgical planning, avoiding nerve injuries during procedures, and achieving successful outcomes in surgical techniques and regional anesthesia blocks.

Conclusion

Ultrasound-guided blocks of distal nerves of the upper limb can rescue a partially effective brachial plexus block. Alternatively, they can be used alongside brachial plexus blocks to prolong analgesia in a specific nerve distribution selectively. They can also be used for motor-sparing functional hand surgery without a tourniquet. On their own, they can provide sensory analgesia (and avoid motor block) in select situations.

Clinical Pearls

- Occasionally the musculocutaneous nerve is not visualized at its typical location within the axillary area. It may lie adjacent to the median nerve, in such cases, leaving the neurovascular bundle more distally. Injection adjacent to the median nerve will block both nerves in this case.

- It is best to block the radial nerve before it divides into its branches (posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm, superficial and deep branches) to ensure complete coverage. Injection should not be too close to the spiral groove to avoid possible nerve damage.12

- Both the median and ulnar nerves are anisotropic. One needs to tilt the ultrasound probe in dorsal-ventral directions to ensure there are effectively visualized.

- Even though it is possible to perform the median or ulnar nerve blocks proximal to the elbow, we recommend performing them distally in the forearm because they lie in the same fascial plane, and performing them through a single insertion point may be possible.

- The ulnar nerve lies closer to the ulnar artery at the distal one-third of the forearm. It diverges away from the ulnar artery as seen on proximal scanning. We perform a mid-forearm level block to avoid proximity to the ulnar artery and an accidental vascular puncture.

References

- Maga JM, Cooper L, Gebhard RE. Outpatient regional anesthesia for upper extremity surgery update (2005 to present) distal to shoulder. Int Anesthesiol Clin 2012;50:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/AIA.0b013e31821a00a8

- Lin E, Choi J, Hadzic A. Peripheral nerve blocks for outpatient surgery: evidence-based indications. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2013;26:467–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0b013e328362baa4

- McCartney CJL, Xu D, Constantinescu C, et al. Ultrasound examination of peripheral nerves in the forearm. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007;32:434–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2007.02.011

- Foxall GL, Skinner D, Hardman JG, et al. Ultrasound anatomy of the radial nerve in the distal upper arm. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007;32:217–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2007.02.006

- Kathirgamanathan A, French J, Foxall GL, et al. Delineation of distal ulnar nerve anatomy using ultrasound in volunteers to identify an optimum approach for neural blockade. Eur J Anaesthesiol2009;26:43–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e328318c5b6

- Fredrickson MJ, Ting FSH, Chinchanwala S, et al. Concomitant infraclavicular plus distal median, radial, and ulnar nerve blockade accelerates upper extremity anaesthesia and improves block consistency compared with infraclavicular block alone. Br J Anaesth 2011;107:236–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer101

- Strandring S. Upper arm. In: Standring S, Gray H. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

- Strandring S. Forearm. In: Standring S, Gray H. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

- Strandring S. Wrist and hand. In: Standring S, Gray H. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2008.

- Maida E, Chiavaras MM, Jelsing EJ, et al. Sonographic visualization of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm: technique and validation using perineural injections in a cadaveric model. J Ultrasound Med 2017;36:1627–37. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.16.08027

- Schwabl C, Hörmann R, Strolz CJ, et al. Anatomical variants of the upper limb nerves: clinical and preoperative relevance. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2023;27:129–35. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1761952

- Latef TJ, Bilal M, Vetter M, et al. Injury of the radial nerve in the arm: a review. Cureus2018;10:e2199. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2199