ASRA Pain Medicine Anticoagulation PBLD - Regional Anesthesia and Pain Procedures in Anticoagulated Patients

A 78-year-old male with a 60-pack year smoking history presents to the emergency room after a fall with imaging confirmed hip fracture. He is visiting his family from out of state, his pulmonologist’s records are not available, and he was “stuck in the ER forever” before being transferred to your institution. He states his “lung doctor” was saying his tests showed severe COPD but he does not remember the numbers. He is on 4L home oxygen and multiple inhalers. He states he was put on sildenafil daily because his pulmonologist was worried about his heart as well. He also has a history of atrial fibrillation. He took both his warfarin and his inhalers.

Bedside transthoracic echocardiography showed moderate right ventricular dysfunction and elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressure. INR from the outside hospital was 3, INR recheck after arriving to this institution is 1.7. The orthopedic team is anxious to fix his hip fracture within 24 hours1.

Discussion Questions

Question 1: How do you provide anesthesia to this patient?

a. General anesthesia w/ ETT

b. Spinal anesthesia

Answer: This is a judgment call for each provider. Of note, a multi-center RCT compared general vs. spinal anesthesia for hip fracture surgery and found no difference in mortality at 60 days or a new inability to walk at 60 days. In addition, this trial also found no difference between anesthesia types in regards to rates of delirium and time to discharge 1,2. Therefore, for the general elderly population having their hip fracture repaired, there is no difference between spinal and general anesthesia.

Spinal anesthesia in those with COPD has been associated with lower morbidity, ventilator dependence, pneumonia, and unanticipated intubation as compared to general anesthesia.3 However, the ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines also state that the risk of spinal hematoma after neuraxial anesthesia varies with age and coagulopathy.4 Rates of spinal hematoma vary between 1 in 22,000 elderly women undergoing spinal anesthesia for hip fracture surgery to 1.38/10,000 for patients having epidural blockade for orthopedic surgery.4 ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines state to hold warfarin for five days prior to elective neuraxial procedure, and to consider reversal of anticoagulation with vitamin K, Prothrombin Complex Concentrate (PCC), or Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) for urgent reversal.4 While FFP might improve their INR further, it may take a variable amount of FFP with variable time and expose the patient to risks of transfusion.5,6,20

Choosing general anesthesia to avoid a bleeding complication is not without risk. As mentioned above, providing general anesthesia to those with COPD can lead to increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications.3 In addition to this risk, his pulmonary hypertension with RV dysfunction places the patient at risk of pulmonary HTN crisis and RV failure after induction of anesthesia.3,7 Hypercarbia and hypoxia are risk factors.7 Placing the patient on mechanical ventilation with PEEP can also lead to RV dysfunction/failure.7 Avoiding an endotracheal tube in this patient and instead choosing an LMA may be an alternative, but carries a higher risk of aspiration as well as more limitations in controlling the patient’s ventilation.

Question 2: Hypothetical - What is your anesthetic plan (general anesthesia vs. spinal anesthesia) if this patient were instead taking 5mg apixaban twice a day instead of warfarin? Their last dose of apixaban was yesterday prior to coming to the emergency room.

a. Proceed with general anesthesia

b. Wait 24 hours and perform spinal anesthesia

c. Check factor Xa activity level or Apixaban plasma level. Consider spinal if ≤0.1 IU/mL or <30ng/mL,

respectively with general anesthesia

Answer: This remains a judgement call for the provider, only if the patient had acceptable, drug-specific calibrated lab values. If the patient’s lab values are greater than the guideline’s recommendations, then the patient should have general anesthesia. Delaying the patient’s hip fracture another 24 hours is not recommended.1

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as apixaban or rivaroxaban, allow for similar stroke prevention efficacy (as compared to warfarin) without routine monitoring.22 Maier et al state that anti-Xa assays that are calibrated to heparin (or uncalibrated) cannot predict levels of medications such as DOACs.23 Anti-Xa levels can be used to assess DOAC activity; however, they must be specifically calibrated to each medication.4,23 The updated ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines on regional anesthesia for patients on anticoagulant medications suggests that a residual apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, etc. level <30mg/mL or a residual anti-Xa activity level ≤0.1 IU/mL is acceptable prior to neuraxial block, deep plexus, or peripheral block.4

The updated 2025 ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines for regional/neuraxial anesthesia do not recommend utilizing reversal agents (andexanet alfa, idarucizumab, PCC, or other) to reverse anticoagulation for neuraxial procedures in routine patients.4

The 2025 guidelines differentiate between low dose and high dose DOACs. The three-day hold period (72 hours) is recommended for patients on high dose apixaban (5mg BID or greater, 2.5mg twice a day in those <60kg or those with significantly reduced kidney function), rivaroxaban (15-20mg once a day, depending on kidney function), edoxaban (30-60mg once a day depending on patient size and kidney function), etc.4 Those with acceptable residual DOAC levels (<30ng/mL) or anti-Xa activity levels (≤0.1 IU/mL) are able to have neuraxial anesthesia or a deep plexus/peripheral block.4

The guidelines suggest different timing for patients on low dose apixaban (2.5mg twice a day) or rivaroxaban (10mg once a day, provided the patient’s CrCl is >15mL/min).4 Those on low dose apixaban are able to have regional anesthesia 36 hours after the last dose and 24 hours after the last low dose rivaroxaban dose (30 hours for patients whose CrCl is 15-30mL/min).4 There are no low dose guidelines for edoxaban.4 Acceptable lab values, detailed above, allow for regional anesthesia procedures earlier than the 24 or 36 hour mark.4

Question 3: What coagulation studies can help guide your neuraxial management in light of anticoagulation?

a. aPTT

b. PT / INR

c. Quantitative Viscoelastic Assay (such as thromboeslastography)

d. Anti-Xa Assay

Answer C is the best answer perioperatively. The role of PT, INR, and aPTT to assess hemostasis and guide blood product management have been called into question.7,8 For patients who have IV heparin regimens, aPTT is valuable to guide dosing.9 Various styles of quantitative viscoelastic assay (for example, thromboelastography) can provide a quantitative look at the kinetics of clot formation and can break down coagulopathy into its parts to guide blood product managemen.10 ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines state to check normal coagulation status after cessation of subcutaneous and IV heparin, in addition to holding the medication for a period of time.4 There are reports of using thromboelastography to assess a patient’s clotting kinetics prior to neuraxial anesthesia, but evidence is limited.11

There is no routine laboratory test for antiplatelet effects of aspirin.9,11 Platelet function assays (such as VASP and VerifyNow assay) are options to assess P2Y12 inhibitors such as clopidogrel.9,21 Anti-Xa assay can be used to assess rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban, etc.4 However, reliable interpretation of anti-Xa assays demands drug specific calibration.4,23 Anti-Xa can also be used to evaluate low molecular weight heparin;4 however, it is usually not assessed unless the patient is on high, therapeutic doses or if there is concern for prolonged activity.4

Thrombin time (TT) and dilute thrombin time (dTT) are recommended by the ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines to monitor dabigatran.4 ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines discuss the poor reliability of PT, INR, aPTT for dabigatran.4

Question 4: What are your warfarin anticoagulation reversal options for your patient?

a. Vitamin K

b. Fresh Frozen Plasma

c. Prothrombin Complex Concentrate

d. Idarucizumab

e. A and B

f. A, B, C

g. All of the above

For reversal of vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin, oral/IV vitamin K and blood products such as FFP and PCC are options. Recommendations from Garcia et al in 2012 discussed for those who are not bleeding and their INR > 4.0, oral vitamin K can reduce the INR within 24 hours.12 While the article uses the non-specific language of “IV vitamin K can work more quickly,” it also states IV vitamin K takes 24 hours for its effect to be fully realized.12 If reversal is required more urgently or the patient is clinically bleeding, FFP and PCC are options4,12 However, each unit of FFP adjusts the INR non linearly,20 and those with a large aberration may require >1500ml of FFP to sufficiently correct their coagulopathy.12,20. In situations where the patient may not tolerate that volume, or clinicians cannot wait for 1500ml to be infused, PCC is available for rapid reversal with a smaller volume.12

Protamine can rapidly reverse heparin, 1mg of protamine for each 100u of heparin. Studies have found thrombocytopenia and impaired platelet activity from protamine,13 and some authors have suggested a protamine-to-heparin ratio of 0.8:1 or titration to advanced clotting time (ACT).13 Those with diabetes who have exposure to protamine containing insulin (NPH formulation) and those with fish protein allergy are at higher risk of an adverse reaction to protamine.13 Hypotension, pulmonary hypertension, and anaphylaxis/anaphylactoid reactions are rare but possibly life threatening.13 Protamine for low molecular weight heparin only reverses its anti IIa activity and not its anti-Xa activity.4 Anti IIa and Xa activity can return three hours after protamine reversal of LMWH.4

Andexanet alfa is a recombinant Xa protein to reverse Xa inhibitors. It is approved to reverse apixaban and rivaroxaban.14 It is a bolus dose then infusion. In addition, PCC or recombinant factor VIIa are options for reversal of Xa inhibitors.4 Be warned that recombinant factor VIIa has risk of thrombotic events with its administration.4

Idarucizumab binds to and reverses dabigatran within minutes.4

Despite these options, ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines state that if there is time to wait for clearance of the medication, discontinuing the anticoagulant is a possible strategy.4

For patients who have a high risk of thromboembolism on warfarin therapy, bridging with IV unfractionated heparin or subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin are options.4

—-Case Progression—

Two days later, the patient is recovering from his hip fracture surgery and is working with physical therapy to improve his mobility. He is on a multi-modal oral and IV pain regimen, yet continues to have significant pain. While in the hospital, his anticoagulation is maintained with IV heparin.

Question 5: What is the best option for regional/neuraxial anesthesia for his pain control?

a. Lumbar epidural catheter

b. Ultrasound guided peripheral nerve catheter

c. Spinal cord stimulator

d. Escalation of his IV pain regimen with a PCA

Answer B is the best choice. While an epidural is also a potent option for pain control while minimizing opioids,15,16 an ultrasound guided peripheral nerve catheter can provide equivalent pain control while having a lower risk of bleeding.15,16 An epidural would require holding his IV heparin 4-6 hours and obtaining a blood test showing normal coagulation (such as an aPTT). Because a peripheral catheter is in a compressible area and bleeding is of less clinical significance (as compared to an epidural hematoma), the European Journal of Anesthesia guidelines do not recommend cessation of IV heparin if the patient is within their therapeutic range.16

Spinal cord stimulators are not indicated for acute pain. They also require a trial period to assess their efficacy prior to permanent implantation. In addition, they are recognized by a group of multiple pain societies as being higher risk for serious bleeding than other central neuraxial procedures.17

Escalation of his pain regimen with PCA is not incorrect, but a nerve catheter would be a superior choice. In a patient who has severe pulmonary disease limiting daily activities, minimizing opioids while maintaining pain control is a good principle. PCA opioid administration is equivalent to other opioid regimens in terms of sedation and respiratory depression side effects while providing improved VAS scores.18 Basal infusions, people other than the patient pushing the PCA button, mechanical error (“runaway pump”), or improper programming of the PCA can increase the risk of respiratory depression.19

— Case Progression —

One year later, the patient has developed failed back surgery syndrome unrelated to his hip fracture. He is discussing a spinal cord stimulator with you, as you provide both anesthesia services and chronic pain services to your physician group.

Question 6: True or False: The ASRA Pain Medicine Pain Management guidelines can be used to manage anticoagulation both acute epidural placement as well as stimulator placement.

a. True

b. False

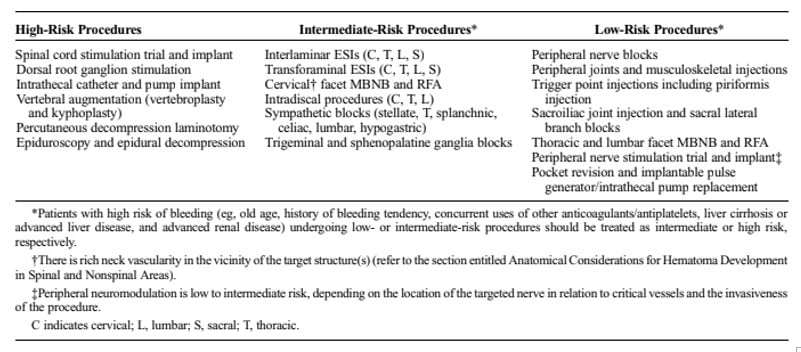

The correct answer is B. A multi-society group met and provided guidelines for other interventional spine procedures and placed a spinal cord stimulator trial and implant in a “high risk” category.17 Other high risk interventional pain procedures are detailed in Table 3. The article discusses that SCS lead placement requires larger gauge needles with a different bevel and stylet that can cause greater damage to any vessel in the epidural space.17 In addition, multiple lead insertion attempts may be required for appropriate neuromodulatory coverage, which could cause greater trauma to the epidural space.17

These interventional spine procedure guidelines recommended similar hold times for clopidogrel (five days), IV heparin (six hours), LMWH (12 or 24 hours, depending on dose), new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) (five half lives, depending on the agent), dabigatran (five half lives).17 It recommended a longer period between a high risk procedure and restarting IV heparin (24 hours). It also stated “consideration should be given” to an ASA or NSAID hold for high-risk procedures, based on each patient.17

Table from Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, Rauck R, Huntoon MA. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 Apr;43(3):225-262. DOI: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000700. PMID: 29278603.

Bibliography

- Welford P, Jones CS, Davies G, et al. The association between surgical fixation of hip fractures within 24 hours and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(7):1176-86.

- Neuman MD, Feng R, Carson JL, et al. Spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia for hip surgery in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(22):2025-35.

- Hausman MS Jr, Jewell ES, Engoren M. Regional versus general anesthesia in surgical patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: does avoiding general anesthesia reduce the risk of postoperative complications? Anesth Analg. 2015;120(6):1405-12.

- Kopp SL, Vandermeulen E, McBane RD, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (fifth edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2025 Jan 29. doi:10.1136/rapm-2024-105766.

- Yazer MH. The how’s and why’s of evidence based plasma therapy. Korean J Hematol. 2010;45(3):152-7.

- Holland LL, Foster TM, Marlar RA, et al. Fresh frozen plasma is ineffective for correcting minimally elevated international normalized ratios. Transfusion. 2005;45(7):1234-5.

- Pilkington SA, Taboada D, Martinez G. Pulmonary hypertension and its management in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(1):56-70.

- Haas T, Fries D, Tanaka KA, et al. Usefulness of standard plasma coagulation tests in the management of perioperative coagulopathic bleeding: is there any evidence? Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(2):217-24.

- Kaushal M, Rubin RE, Kaye AD, et al. Anticoagulation and neuraxial/peripheral anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(2):e21-39.

- Wikkelsø A, Wetterslev J, Møller AM, et al. Thromboelastography (TEG) or rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to monitor haemostatic treatment in bleeding patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(4):519-31.

- Bauer ME, Arendt K, Beilin Y, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Interdisciplinary Consensus Statement on neuraxial procedures in obstetric patients with thrombocytopenia. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(6):1531-44.

- Garcia DA, Crowther MA. Reversal of warfarin: case-based practice recommendations. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2944-7.

- Boer C, Meesters MI, Veerhoek D, et al. Anticoagulant and side-effects of protamine in cardiac surgery: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(5):914-27.

- Reed M, Tadi P, Nicolas D, et al. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Rawal N. Current issues in postoperative pain management. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33(3):160-71.

- Kietaibl S, Ferrandis R, Godier A, et al. Regional anaesthesia in patients on antithrombotic drugs: Joint ESAIC/ESRA guidelines. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2022;39(2):100-32.

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, et al. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications (second edition): guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(3):225-62.

- McNicol ED, Ferguson MC, Hudcova J. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus non-patient controlled opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(6):CD003348.

- Pastino A, Lakra A. Patient-Controlled Analgesia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- O’Brien M, Hayes B. INR reduction with FFP - how low can you go? Academic Life in Emergency Medicine. Available from: https://www.aliem.com/inr-reduction-ffp/

- Benzon H, Jabri R, Van Zundert T. Neuraxial anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks in patients on anticoagulants. NYSORA Topics. Available from: https://www.nysora.com/topics/foundations-of-regional-anesthesia/patient-management/neuraxial-anesthesia-peripheral-nerve-blocks-patients-anticoagulants/

- Eikelboom JW, Quinlan DJ, Hirsh J, et al. Laboratory monitoring of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(5):566-74. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0364

- Maier CL, Sniecinski RM. Anticoagulation monitoring for perioperative physicians. Anesthesiology. 2021;135(4):738-48. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003903. Erratum in: Anesthesiology. 2022;136(1):252.

s. B, a 62-year-old female with recent IV Drug Use (IVDU) and Opioid Use Disorder (on chronic methadone managed by a clinic), CAD s/p CABG, HFrEF (EF 48%), COPD presented to the hospital with acute on chronic abdominal pain found to have perforated gallbladder s/p open cholecystectomy.

On POD #1 states that pain is localized to the R-side and describes both incisional pain and deep R-sided visceral intrabdominal pain. States that pain is constant and worsens with movement. Vitals are stable. Physical exam is notable for ~7-inch incision in the RUQ of the abdomen with mild tenderness to palpation. No abdominal guarding or rebound.

Discussion Questions:

1. What type of multimodal analgesia can we offer this patient?

Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) on methadone maintenance treatment may experience episodes of acute pain related to injury, illness, or in the case of our patient, postoperative incisional and visceral pain. For these individuals, the daily methadone dose prescribed for the treatment of OUD is to be continued alongside aggressive multimodal analgesia (MMA) which might include non-opioid analgesics, regional anesthesia techniques, non-opioid infusions (e.g. ketamine, lidocaine), clonidine, gabapentinoids, skeletal muscle relaxants, physical modalities (e.g., cold, heat, or splinting), integrative therapies, and psychosocial or behavioral management strategies.1 Special consideration should be given to relevant factors that may influence the selection of multimodal analgesic options such as the presence of heart failure and use of COX-2 or non-selective NSAIDs in our patient, for example.2,3 Emphasis should be placed on maximizing the use of nonpharmacologic modalities and nonopioid agents. Should non-opioid strategies fail to adequately control the patient’s pain, MMA should be continued while opioids are initiated to reduce total opioid requirement.4

2. Does the methadone dose prescribed for the treatment of OUD provide analgesia for the patient?

While methadone can be effective in treating both OUD and acute pain, its typical duration of analgesic action is only about four to eight hours. Further, in the context of increased pain severity, it is unlikely that the patient's once daily maintenance dose of methadone intended to treat their OUD will be adequate to treat their postoperative acute pain.5

Managing acute pain in patients with OUD on methadone maintenance treatment involves the continuation and single administration of the patient’s established daily methadone dose while optimizing the utilization of non-opioid multimodal analgesia for pain control throughout the day. Of note, in some instances, methadone can be divided into three equal doses administered every eight hours in order to maximize analgesic benefit with a plan to resume baseline single-dose administration prior to discharge.1

Any changes to the patient’s methadone dose or care plan should be discussed with the patient, including when it might be prudent to order supplemental opioids. At discharge, it is important to consult the patient’s licensed opioid treatment program to ensure that a solid plan has been established to help facilitate a safe return to baseline.

3. Does use of opioid use inpatient to treat pain result in increased risk of relapse for OUD?

Patients with OUD may face several challenges in the immediate postoperative period and risk of relapse during this time is not limited to inpatient opioid consumption alone. Physiologically, previous studies have demonstrated that individuals with a history of prolonged opioid maintenance have long term differences in pain sensitivity.7 This is one of the reasons why pain control in this patient population is more challenging than opioid-naïve patients. While providers and patients alike may worry about balancing inadequate pain relief, triggering opioid withdrawal and the risk of relapse, adequate pain treatment is essential as undertreated pain can drive poor health outcomes including in hospital drug use, stigma, mistrust of the health care system and patient directed discharges.8 To minimize the risk of relapse, all non-opioid analgesia should be maximized including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, gabapentinoids, alpha 2 receptor agonists, dexamethasone, and ketamine or lidocaine infusions (as outlined in question 1). Anxiolytic therapies—both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic—may prove beneficial as the anxiety surrounding surgery and hospitalization can present as a significant stressor and lead to cravings or relapse. Additionally, the use of regional anesthesia after some orthopedic surgeries has also been shown to decrease the amount of opioids consumed 0-24 hours postoperatively which may further reduce the risk of relapse.9 Therefore, regional anesthesia should be offered to patients postoperatively as an important component of multimodal analgesia. Lastly, OUD medications including buprenorphine or methadone can be lifesaving. Hospitalization and acute illness can be an opportunity to initiate OUD medications,11 and a new study demonstrates that these medications can also decrease the risk of overdose after surgery.10 In summary, the risk of relapse postoperatively is high, and causes are multifactorial including inadequately treated pain, psychosocial stressors, and prolonged use of prescription opioids postoperatively. Patients with OUD should also have close follow-up with an addiction specialist or chronic pain provider upon discharge.

4. Is there an increased risk of respiratory depression if a patient is given more opioids on top of their maintenance methadone dose?

Patients receiving chronic methadone therapy for opioid use disorder (OUD) have developed significant tolerance to the respiratory and central nervous system (CNS) depressant effects of opioids. This tolerance is a protective factor against severe respiratory depression when additional opioids are administered for acute pain. Furthermore, acute pain itself serves as a physiological antagonist to opioid-induced respiratory depression, as evidenced by studies showing minimal respiratory complications when opioids are added in the context of acute pain. While the theoretical risk of additive respiratory depression exists, it has not been clinically substantiated, even in settings requiring higher opioid doses for pain relief. Tolerance to respiratory depression has been described as occurring rapidly, within a period of days, further supporting the recommendation that clinicians can feel comfortable adding short-acting opioid analgesics to a stable methadone regimen for a patient with a history of OUD.12

5. Given that this patient is taking chronic methadone, how do we treat acute on chronic pain?

Effective acute pain management in patients on maintenance methadone therapy necessitates a dual approach: addressing baseline opioid dependence and managing the acute pain with additional analgesics. Methadone’s analgesic effect lasts only four to eight hours, far shorter than its withdrawal-suppressing effects, leaving these patients vulnerable to inadequate pain control. Additionally, opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia—heightened pain sensitivity caused by long-term opioid use—require that these patients receive higher and more frequent doses of opioid analgesics compared to opioid-naïve individuals. To mitigate these challenges, the maintenance methadone dose should be continued, verified through the prescribing clinic or physician, and supplemented with short-acting opioids administered on a scheduled basis rather than as-needed. This ensures continuous pain relief while minimizing withdrawal symptoms and hyperalgesia. To optimize outcomes, pain management strategies should prioritize multimodal analgesia, including non-opioid medications like acetaminophen or NSAIDs, and adjuvant therapies such as tricyclic antidepressants. Avoid mixed agonist-antagonist opioids to prevent withdrawal. Furthermore, physicians must complete this medicine reconciliation to communicate between the inpatient and outpatient teams to ensure that the outpatient team is aware that the patient is receiving prescribed alternative opioid analgesics in the acute care setting. This communication reduces the risk that the outpatient methadone clinic suspects misuse if alternative opioids are noted on urine drug screens.12

6. Is Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) safe and effective for opioid tolerant patients?

PCA can be a safe and effective pain management strategy for opioid-tolerant patients when properly managed. These patients often have higher opioid requirements due to tolerance, and PCA allows them to self-administer analgesia within prescribed limits, reducing delays in pain relief. Additionally, PCA minimizes staff bias and variability in administering analgesia. However, careful considerations are necessary, particularly regarding the use of a basal rate, which should generally be avoided or used cautiously in opioid-naïve patients. While basal dosing may benefit opioid-tolerant patients when combined with demand dosing, it is typically reserved for those with terminal cancer pain and is not recommended for patients with OUD due to the increased risk of overdose and respiratory depression. Dosing parameters should start with higher initial demand doses and shorter lockout intervals to account for tolerance, with adjustments based on patient response and side effects. Close monitoring is essential to detect sedation, respiratory depression, or other opioid-related side effects, especially in patients with comorbidities such as COPD and HFrEF.13,14

a. How do you safely wean PCAs and transition to an oral regimen?

Transitioning from PCA to an oral regimen requires a structured approach. The first step is assessing the patient’s pain control and functional status, ensuring that pain is manageable with PCA demand doses alone and confirming the patient’s ability to tolerate oral intake. Next, calculate the total daily opioid requirement and convert it to an appropriate short-acting oral opioid while incorporating a cross-tolerance reduction of approximately 25-50%. Provide a short-acting opioid for breakthrough pain, typically 10-15% of the total daily dose, ensuring adequate pain relief while minimizing the risk of overuse. According to the 2022 CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain, extended-release and long-acting opioids should generally be reserved for cancer-related pain and are not recommended for patients with OUD due to the increased risk of misuse and overdose. If an extended-release opioid is considered for non-cancer pain, it should be done with careful justification, close monitoring, and a clear plan for tapering. Gradual weaning from PCA is recommended, ensuring that the patient transitions safely to oral medication. During this process, frequent monitoring to assess pain and sedation levels every one to two hours for the first 24-48 hours is crucial, as patients are at the highest risk of hypoventilation and nocturnal hypoxemia during this period. These recommendations align with the CDC guidelines, which emphasize cautious opioid prescribing, risk mitigation strategies, and individualized patient-centered approaches to pain management.15

To optimize pain control, multimodal analgesia should be the foundation of therapy, with non-opioid medications serving as the mainstay of treatment. Acetaminophen, NSAIDs (if not contraindicated), and adjuvants such as gabapentinoids should be prioritized to provide effective baseline analgesia. Opioids should be used as adjuncts for breakthrough pain rather than as the primary modality, helping to enhance pain relief while minimizing opioid-related side effects and risks. By following these steps, health care providers can safely transition patients from PCA to oral analgesia, ensuring effective and comprehensive pain management.13,14

7. What are the ethical considerations and challenges in managing pain for patients with a history of intravenous drug use, and how can health care providers address potential biases to ensure equitable care?

When managing pain in patients with a history of intravenous drug use, several ethical principles come into play. Autonomy requires respecting the patient’s right to pain relief and honoring their established treatment plans, such as chronic methadone therapy. Beneficence emphasizes the need to provide optimal pain management to enhance recovery and minimize suffering, while nonmaleficence urges providers to carefully balance effective pain control against the risks of exacerbating a substance use disorder or inducing overdose. Justice demands that health care providers deliver equitable care without bias or discrimination, ensuring that all patients receive appropriate treatment regardless of their history.

Despite these guiding principles, health care providers often face hesitations when managing pain in this population. Concerns about drug misuse or diversion may lead to reluctance in prescribing opioids, driven by fear that such treatments could worsen the patient’s addiction. Stigma and bias further contribute to the under-treatment of pain, as misconceptions about individuals with a history of drug use influence clinical decision-making. Additionally, determining appropriate opioid doses for a tolerant patient can be challenging, as providers must avoid both under-dosing and the risks associated with overdose or withdrawal. Regulatory pressures, including heightened scrutiny of opioid prescriptions, also compound hesitations, making some providers wary of prescribing adequate pain medications.

To address these challenges, health care providers can take several steps. Education is essential to help providers balance addiction management with ethical pain treatment. Evidence-based guidelines for managing pain in patients with OUD offer a structured approach to care. Engaging addiction specialists and pain management teams fosters a collaborative, multidisciplinary strategy. Open communication with the patient builds trust, allowing providers to discuss care goals, pain expectations, and safe opioid use. Finally, tools like prescription drug monitoring programs and naloxone education can help mitigate risks and support safer prescribing practices. By combining ethical principles with practical strategies, providers can ensure that patients with a history of intravenous drug use receive compassionate, equitable, and effective pain management.16,17,18 s

8. What community resources should we connect patients with upon hospital discharge?

Community resources play a crucial role in the management of OUD providing patients with support beyond clinical settings. Physicians should connect patients with medication-assisted treatment (MAT) programs, such as those that provide buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone, which are evidence-based approaches proven to reduce opioid cravings and prevent relapse.19 Unfortunately, only a small percentage of people eligible for MAT in the United States participate in treatment, and MAT programs often have patient retention issues.20

Physicians should become familiar with harm reduction services, including syringe exchange programs and naloxone distribution, which are essential for minimizing the risks associated with opioid use while maintaining patient safety.21 Peer support groups, such as Narcotics Anonymous or SMART Recovery, provide patients with social support, self-empowerment, and accountability which are vital for overcoming a substance use disorder.22 Additionally, social service agencies that address housing, employment, and food insecurity can help stabilize patients’ lives and reduce relapse triggers.

Physicians should collaborate with multidisciplinary teams within their help system, including case managers, social workers, and community health workers, to ensure patients have access to these resources. Evidence shows that comprehensive, community-based approaches improve long-term outcomes for individuals with OUD.

References:

- Wakeman S, Zeballos J. (2024). Management of acute pain in patients with opioid use disorder. UpToDate. Retrieved December 22nd, 2024 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-acute-pain-in-patients-with-opioid-use-disorder

- Goodlin, S. J., Wingate, S., Albert, N. M., Pressler, S. J., Houser, J., Kwon, J., Chiong, J., Storey, C. P., Quill, T., Teerlink, J. R., & PAIN-HF Investigators (2012). Investigating pain in heart failure patients: the pain assessment, incidence, and nature in heart failure (PAIN-HF) study. Journal of cardiac failure, 18(10), 776–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.07.007

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain - United States, 2022. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports, 71(3), 1–95. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Buys M. (2024). Use of opioids for acute pain in hospitalized patients. UpToDate. Retrieved December 22nd, 2024 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/use-of-opioids-for-acute-pain-in-hospitalized-patients

- Durrani, M., & Bansal, K. (2024). Methadone. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved December 22nd, 2024 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562216/

- Ward, Emine Nalan, et al. “Opioid Use Disorders: Perioperative Management of a Special Population.” Anesthesia and Analgesia, vol. 127, no. 2, Aug. 2018, p. 539. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003477.

- Wachholtz, Amy, and Gerardo Gonzalez. “Co-Morbid Pain and Opioid Addiction: Long Term Effect of Opioid Maintenance on Acute Pain.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 145, Dec. 2014, pp. 143–49. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.010.

- Simon, Rachel, et al. “Understanding Why Patients with Substance Use Disorders Leave the Hospital against Medical Advice: A Qualitative Study.” Substance Abuse, vol. 41, no. 4, 2020, pp. 519–25. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1671942.

- Cunningham, Daniel J., et al. “Regional Anesthesia Decreases Inpatient But Not Outpatient Opioid Demand in Ankle and Distal Tibia Fracture Surgery.” Foot & Ankle Specialist, vol. 17, no. 5, Oct. 2024, pp. 486–500. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/19386400221088453.

- “Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Associated with Decreased Risk of Overdose after Surgery, Suggests First-of-Its-Kind Study of over 4 Million Surgeries.” American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), 14 Oct. 2023, www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/10/opioid-use-disorder-treatment.

- Wakeman SE, Rich JD, Rich JD, Wakeman SE. Treating Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical Settings. 1st Edition 2021. Springer International Publishing AG; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-80818-1

- Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Jan 17;144(2):127-34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00010. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2006 Mar 21;144(6):460. PMID: 16418412; PMCID: PMC1892816.

- Pastino A, Lakra A. Patient-Controlled Analgesia. [Updated 2023 Jan 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551610/

- Mayoral Rojals V, Charaja M, De Leon Casasola O, Montero A, Narvaez Tamayo MA, Varrassi G. New Insights Into the Pharmacological Management of Postoperative Pain: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2022 Mar 10;14(3):e23037. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23037. PMID: 35419225; PMCID: PMC8994615.

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep 2022;71(No. RR-3):1–95. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Kotalik J. Controlling pain and reducing misuse of opioids: ethical considerations. Can Fam Physician. 2012 Apr;58(4):381-5, e190-5. PMID: 22611604; PMCID: PMC3325448.

- Cheetham A, Picco L, Barnett A, Lubman DI, Nielsen S. The Impact of Stigma on People with Opioid Use Disorder, Opioid Treatment, and Policy. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2022 Jan 25;13:1-12. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S304566. PMID: 35115860; PMCID: PMC8800858.

- St Marie B, Broglio K. Managing Pain in the Setting of Opioid Use Disorder. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020 Feb;21(1):26-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.08.003. Epub 2019 Oct 21. PMID: 31648905; PMCID: PMC6980723.

- Leshner AI, Mancher M, eds. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. National Academies Press; 2019.

- Chan B, Gean E, Arkhipova-Jenkins I, et al. Retention strategies for medications for opioid use disorder in adults: a rapid evidence review. J Addict Med. 2021;15(1):74-84. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000739

- Aspinall, E. J. et al (2014). Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol, 43(1), 235- 248. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt243

- Ries RK, Miller, SC, Fiellin, DA, Saitz, R (Eds.) Principles of Addiction Medicine, Fourth Edition. American Society of Addiction Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2009.