Upper Extremity Nerve Blocks: A Problem-Based Learning Discussion

Learning Objectives

- Identify the four major upper extremity (UE) blocks and their anatomical landmarks.

- Predict anesthetic coverage and diagnose block failure based on brachial plexus anatomy.

- List the coverage, side effects, and potential complications of each regional anesthesia technique (axillary, interscalene, supraclavicular, infraclavicular nerve blocks, and bier blocks).

- Explain how risks common to UE blocks vary by block location.

- Determine which upper extremity blocks are appropriate for a given clinical scenario based on pertinent surgical and medical considerations.

- Demonstrate this knowledge through application in clinical scenarios.

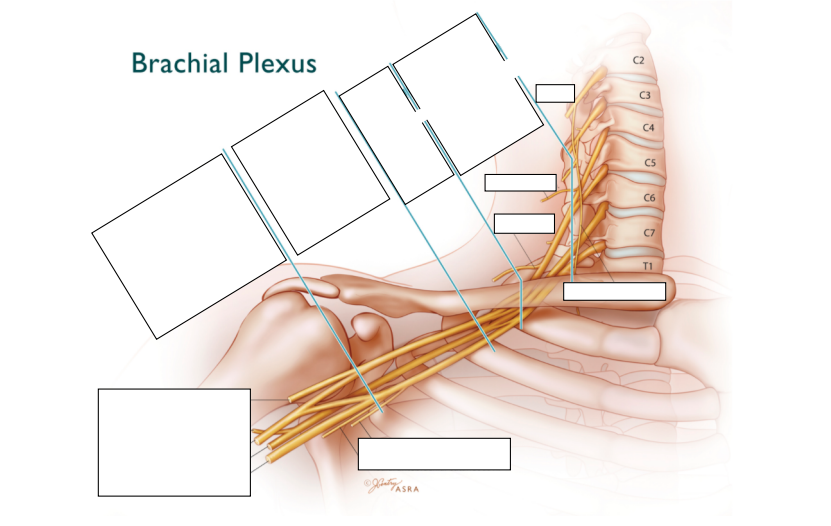

Can you name the cords of the brachial plexus and which terminating nerves each cord produces? Draw the brachial plexus anatomy and main terminating nerves.

Case 1

A 55-year-old male presents for open reduction internal fixation surgery for a left distal radius Colles fracture. His past medical history (PMH) is significant for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity (BMI 44). Physical exam reveals macroglossia, a beard, increased neck circumference, short thyromental distance, and a mallampati score of 3. The surgeon always requests general anesthesia (GA) and post-anesthesia care unit pro re nata blocks to avoid delays.

What in this patient’s history would help you decide between regional anesthesia vs. GA?

- The patient’s physical exam raises concerns for a possible difficult airway. While there is some argument for securing a potentially difficult airway preemptively, maintaining spontaneous ventilation would be the safest option for this patient. His physical exam also suggests he would be a poor candidate for narcotic-based postop analgesia.

Which block would you choose? What are some considerations that will determine the choice of an upper extremity block?

- This surgical site is distal and involves the radial, ulnar, and median nerves. An interscalene block commonly spares C8-T1 and would leave the ulnar and parts of the median nerve uncovered. Supraclavicular and infraclavicular blocks would cover the site but still carry a meaningful risk of ulnar nerve-sparing. An axillary nerve block would ensure coverage of all three nerve branches.

- The patient’s history and physical exam can also influence our ability to position and conduct an ultrasound-guided nerve block. This patient is large and might have difficulty positioning his arm due to his fracture, which may make getting a good infraclavicular view difficult. While the risk of phrenic nerve involvement is less common with supraclavicular blocks than interscalene blocks, the risk should still be taken into consideration as this patient would likely develop ventilation and oxygenation issues if phrenic nerve palsy were to occur. An axillary nerve block would avoid these risks but would preclude placement of a catheter.

Would the intercostobrachial nerve be covered by one of these brachial plexus blocks?

- The intercostal brachial nerve is not part of the brachial plexus and would not be covered by any of these blocks. It comes off the T2 intercostal nerve as a lateral branch. It travels from the chest wall to the bottom of the axilla to innervate the medial and axillary portions of the arm.

Would an intercostal brachial nerve block also be required for this surgery? Why might communication with the surgery team be important in determining if this block is also required?

- The intercostal brachial nerve is an important component of cuff pain. While some argue that an intercostal brachial nerve block is unnecessary and/or ineffective at blocking tourniquet pain, it is commonly employed to mitigate this discomfort. Communicating with the surgical team to determine if they will need a tourniquet for the distal arm procedure is therefore important for block planning. Subcutaneous infiltration in the medial or axillary floor of the upper arm is the most common way to block the intercostobrachial nerve although infiltration within the PECS II plane or just above the second rib will also effectively block the nerve.

Case 2

A 79-year-old female presents for a left shoulder arthroplasty for which she will be admitted. She has a past medical history significant for right diaphragmatic paralysis s/p surgical resection of a bronchogenic carcinoma involving the phrenic nerve five years ago. The surgical team requests a block for the primary anesthetic and postoperative pain control.

Would you choose to block this patient? If so, which block would you choose?

- Given the patient’s diaphragmatic paralysis on the right, an interscalene block cannot be safely performed in this patient since it would most likely cause phrenic nerve paralysis on the left. Additional risks of an interscalene block include vascular damage, intravascular injection (especially into the vertebral artery), and epidural spread (although these are rare with ultrasound-guided blocks).

If the surgeon asked if you could perform the block in a way that mitigated the risk of phrenic nerve block, what would you say?

- Decreasing the concentration of the local anesthetic and the volume may reduce this risk but cannot eliminate it. Leaving a catheter in place and using shorter-acting anesthetics would provide a way to rescue phrenic nerve involvement, either by allowing the block to wear off or washing it out with saline, but subsequent phrenic nerve blockade has to be assumed when placing an interscalene block. A cervical erector spinae plane block could be considered for post-op analgesia but would not provide surgical anesthesia.

If the patient instead has nerve compression causing right vocal cord paralysis, could a block be conducted for this surgical procedure?

- The exact incidence of ipsilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve secondary to interscalene block is unknown. However, it is less likely than phrenic nerve block. Nevertheless, clinicians must weigh the risks and benefits in a patient who already has cord paralysis.

Case 3

A 55-year-old male with end-stage renal disease presents for surgical placement of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF). Other medical history is significant for obesity, hypertension, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

What considerations should you take into account when deciding your anesthetic choice?

- Have a discussion with the surgical team regarding the use of a regional technique with sedation versus the use of a general anesthetic. In the clinical scenario above, the benefits of using a regional technique include increased local blood vessel diameter, increased blood flow, and postoperative fistula patency, which result in an increased opportunity for a successful AVF creation with long-term patency. This is in addition to avoidance of hemodynamic instability.

- The location of the AVF will determine the choice of block. Options include supraclavicular block, infraclavicular block, and axillary block.

- If the patient’s COPD is severe with home oxygen use, a lower block should be considered to avoid phrenic nerve involvement. If the patient is on blood thinners for his atrial fibrillation, an axillary block should be considered for ease of compression should vascular damage occur.

Under what circumstances in this scenario would you consider a supraclavicular block or infraclavicular block?

- Supraclavicular block targets the trunks and/or divisions of the brachial plexus, providing coverage to the entire upper extremity distal to the shoulder. Infraclavicular blocks target the cords of the brachial plexus and has similar coverage. The axillary block targets the branches of the brachial plexus. In the above scenario, the location of the AVF should be considered when planning your regional technique.

- In a supraclavicular block, the location of the needle puncture is at the midpoint of the clavicle, just cephalic posterior to the subclavian artery. Given this location, there is a concern for phrenic nerve injury and pneumothorax (right>left as apex of lung is greater on right). This is particularly concerning in patients with lung pathology and obesity, where rescue breathing may be more difficult. An infraclavicular block has the advantage of having a reduced risk of inadvertently blocking the phrenic nerve but can be difficult to visualize and target in obese patients. Axillary nerve blocks provide easy visualization and provide dependable coverage although identifying and targeting each individual branch (especially the musculocutaneous) can be time-consuming. (Single injections next to the artery are reasonably effective but have become less common with ultrasound use.)

What additional block may be added to either a supraclavicular or infraclavicular approach to aid in coverage of the medial aspect of the upper arm? When would this be most relevant?

- The intercostobrachial nerve covers the medial aspect of the upper arm. For AVF creation above the elbow, this block may be added for better anesthetic coverage.

A supraclavicular block is placed preoperatively with special attention given to targeting the “corner pocket” to avoid ulnar sparing. The patient reports their arm is heavy and numb as you roll back to the OR. As the surgeons begin the procedure for AVF creation in the snuff box, the patient reports sharp pain to the incision. What is wrong and what can you do?

- Radial nerve-sparing is not typical when placing supraclavicular nerve blocks but can occur when the local anesthetic spread is insufficient, and the superficial aspects of the trunks/divisions are not supplemented.

- Distal nerve branches can be quickly supplemented with low volumes of anesthetic under ultrasound guidance to rescue insufficient blocks. After coursing through the radial groove, the radial nerve travels anterior to the lateral epicondyle through the cubital fossa. Since it can split into its deep and superficial branches early after emerging from the cubital fossa, it is often prudent to find and block the nerve near the elbow. The ulnar and median nerves can similarly be blocked in the event of partial block failure by locating them at or distal to the elbow.

Case 4

A 60-year-old female presents for carpal tunnel release under regional anesthesia. Her PMH is notable for median nerve dysfunction in her hand, type II diabetes, and a history of shoulder arthroplasty. She says she received a nerve block for her arthroplasty and found the sensation of having a “dead arm” profoundly unsettling. She says it provoked her anxiety and requests that you do not perform a nerve block. The surgeon does not feel comfortable with just using local.

Other than GA, what else could you offer?

- Intravenous regional anesthesia (Bier block) is a technique that provides surgical anesthesia for fast procedures (expected to be less than one hour) without targeting individual nerves. It also is notable for being quickly reversible after the procedure is concluded.

As you consent this patient, what risks are you considering?

- While Bier blocks negate the risk of individual nerve injury, phrenic nerve involvement, pneumothorax, bleeding that’s associated with other upper extremity nerve blocks, the risk of local anesthetic toxicity (LAST), and block failure need to be carefully considered.

How is a Bier block placed and managed? What are the most important steps?

- An IV is placed in the patient's surgical hand. The patient’s arm is exsanguinated with an Esmarch bandage after which the axillary nerve is compressed and a double-cuffed tourniquet’s proximal cuff is inflated either at the bicep or forearm. 30-50 cc of 0.5% lidocaine is then injected into the IV which is subsequently removed. (Additives may be used to provide postoperative analgesia.)

- The surgery begins once the lidocaine has diffused into the tissue. After 30-40 minutes, or when the patient complains of tourniquet pain, the distal tourniquet cuff is inflated and the proximal is deflated.

- No matter how short the procedure is, the tourniquet should not be deflated for 30-40 minutes after local anesthetic injection to avoid symptoms of LAST. Some additionally argue for a quick tourniquet deflation and re-inflation when the surgery is over to keep any remaining intravascular local anesthetic from entering the circulation all at once.

After placing the block, the surgeon begins the procedure, but the patient’s arm still is not numb. What may have gone wrong?

- Bier blocks set up quickly, however it does take some time for the distal nerves to become anesthetized. If the block does fail, it is most commonly because the arm was not adequately exsanguinated and the local anesthetic is in the blood, not the tissue.

The surgery is successful but on deflating the cuff, the patient begins to complain of tingling in her lips. As you try to assess for other symptoms of LAST, she becomes agitated and says she is having a panic attack. What is wrong, how did it happen, and what do you do?

- LAST symptoms are dependent on local anesthetic concentration and begin with peripheral symptoms, classically tingling of the lips. This can evolve into neurologic symptoms including ringing in the ears, disinhibition, and seizures. Cardiac toxicity usually requires higher intravascular concentrations and commonly occurs after this prodrome, although all these symptoms can come in rapid succession.

- LAST symptoms after a Bier block typically occur when the tourniquet is taken down while a significant portion of the local anesthetic remains intravascular (has not been absorbed into the tissue). Tourniquet failure, early termination of surgery, or accidental deflation can all lead to symptoms of LAST.

- The treatment for LAST is intralipid and regional anesthesia should never be attempted if it is not immediately available.

Further Reading

- Neal JM, Gerancher JC, Hebl JR, et al. Upper extremity regional anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding, 2008 [published correction appears in Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010 Jul-Aug;35(4):407]. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(2):134-170.

- Collins A, Gray A. Peripheral Nerve Blocks. In: Stoelting RK, Miller RD. Basics of Anesthesia. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingston; 2000.

- Chan CW, Peng PW. Suprascapular nerve block: a narrative review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2011;36(4):358-373.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top