Supraclavicular Block

Authors

Brandon Michael Togioka, MD

Resident Physician

Christopher L Wu, MD

Professor

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Baltimore, MD

Introduction

Regional anesthesia for upper extremity surgery has many advantages over traditional general anesthesia with systemic opioids. Among these advantages are more effective postoperative analgesia, decreased requirements for systemic opioids and the potential complications associated with their use, and an ability to avoid instrumenting the airway.[1] If performed by experienced operators it can provide successful surgical anesthesia in a high majority of cases (94.2–94.7%) with a very low complication rate.[2-4]

The supraclavicular block, first described by Kulenkampf, provides a consistent homogenous blockade of the entire upper extremity without preferentially sparing the cephalad (musculocutaneous) or caudad (ulnar) nerves of the brachial plexus.[5] The popularity of the supraclavicular approach to block the brachial plexus substantially increased with the introduction of ultrasound technology as it greatly reduced the incidence of pneumothorax. Prior to the introduction of ultrasound, the pneumothorax rate was reported between 0.6% and 5%.[6] This rate is now very low as evidenced by the lack of any reported pneumothoracies in four publications with a combined patient population of 2,590.[2][4][6-7] Thus, the ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block will be described below.

It should be noted that some clinicians prefer to use nerve stimulation as an adjunct to ultrasound-guided nerve blockade. This technique has been shown to have limited utility.[8] Positive motor response to nerve stimulation has not been shown to increase the success rate of a block and in one study 90% of patients without a motor response still had a successful block, which was defined as one that sufficed as sole anesthetic.[8]

Indications

The brachial plexus is often blocked at the supraclavicular level for procedures that will require anesthesia from the mid-humeral level down to the hand.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to placing a supraclavicular block include patient refusal, infection at the proposed site of needle insertion, severe allergy to local anesthetics and patients with severe respiratory compromise in whom diaphragmatic hemiparesis could be fatal. Some relative contraindications include uncooperative patients, patients with coagulopathies, preexisting neurologic deficits in the distribution of the brachial plexus, and patients with abnormal anatomy.

Anatomy

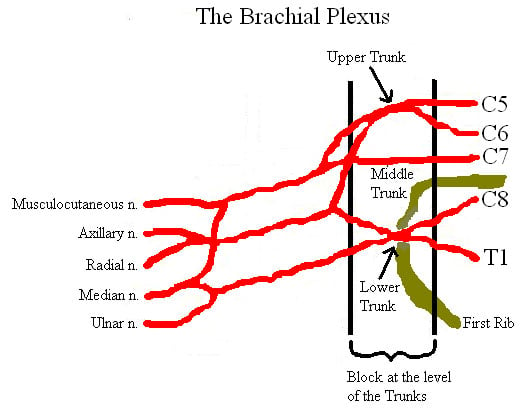

The brachial plexus comes off of spinal cord as the ventral (anterior) rami of nerve roots C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1. As these roots course distally they rearrange to form trunks, divisions, cords, and lastly branches in sequential order. The supraclavicular approach to blocking the brachial plexus is thought to occur at the level of the nerve trunks or divisions. The brachial plexus is most compact at the level of the trunks and so injecting local anesthetics here gives the greatest likelihood of blocking all the branches of the brachial plexus.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the brachial plexus and its branches

The brachial plexus and subclavian artery course under the clavicle and above the first rib. Once the subclavian artery is located, the clinician should look laterally and posteriorly to locate the trunks and divisions of the brachial plexus. At this level it is easy to inadvertently give the patient a pneumothorax as the pleura is located just under the first rib or usually 1 to 2 cm inferior to the brachial plexus.

Technical Considerations

Patient Position

Position the patient supine with arm placed by their side with their head turned such that their face is looking away from the arm to be blocked.

Equipment

- Sterile gown, gloves, cap, mask

- Standard ASA monitors with intravenous access

- Oxygen by nasal cannula

- 2% chlorhexidine skin preps

- 25 G, 3.8 cm needle for local anesthesia

- Local anesthetic with 1:200,000 epinephrine

- High Frequency 10-15 MHz linear probe

- Drugs for sedation such as midazolam and fentanyl, if desired

- 22 G, 5 cm insulated simulating needle, if desired

Medications

- 5 cml Fentanyl and 5 mL Midazolam for sedation (likely not all will be used)

- Local anesthetics

- Mepivacaine/Lidocaine 1 to 1.5% will provide 2–3 hours of surgical anesthesia without epinephrine and 3–5 hours with epinephrine

- Bupivacaine/Ropivacaine 0.25 to 0.5% will provide 4–6 hours of surgical anesthesia without epinephrine and 8–12 hours with it

Ultrasound Guided Technique

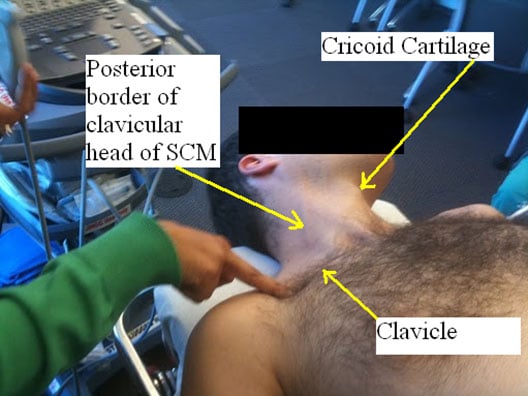

Palpate the posterior border of the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the level of the cricoid cartilage (C6).

Figure 2. Surface anatomical landmarks for supraclavicular block

Now lightly sweep your fingers laterally until they fall into the interscalene groove.

Figure 3. Palpation of the interscalene groove

Follow the interscalene groove to a point about 1 cm above the clavicle—this is the site for needle insertion. After skin sterilization place the ultrasound probe over the supraclavicular fossa parallel to the clavicle and perpendicular to the skin.

Figure 4. Ultrasound probe placed above the clavicle in the supraclavicular fossa

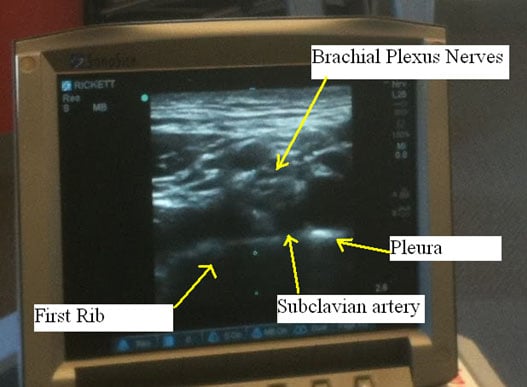

Adjust the ultrasound machine to give a depth of view of approximately 2 to 3 cm. This will give a transverse view of the subclavian artery and brachial plexus and show several hypoechoic (tissue that does not reflect ultrasound waves and is thus dark on the screen) structures under ultrasound. Look first for the round pulsating hypoechoic subclavian artery just medial and superior to the first rib. Immediately lateral to the subclavian artery and superior to the first rib one will see a bunch of hypoechoic oval structures which are the trunks or divisions of the brachial plexus. Also locate the pleura immediately inferior to the first rib. It is important to identify the pleura by finding an echogenic (bright) line immediately inferior to the first rib that moves with respiration.

Figure 5. Ultrasound showing the brachial plexus and neighboring structures (subclavian artery, first rib and pleura)

At this point it is important to note the skin-to-brachial plexus and skin-to-pleura distance on the ultrasound monitor. Keep these distances in mind to avoid giving the patient a pneumothorax.

After numbing the skin in the area of proposed needle insertion, insert your blocking needle along the lateral end of the ultrasound probe. Advance the needle along the long axis of the ultrasound probe in a lateral to medial direction watching it in real time as the needle approaches the brachial plexus. Continue to observe the depth of needle insertion keeping in mind the skin-to-brachial plexus and skin-to-pleura distances previously calculated. This is one block where continuous visualization of the needle tip is critical to avoid a pneumothorax given the close proximity of the brachial plexus to the apex of the lung.

If the needle tip is not clearly in view injecting small amounts of 5% dextrose can be useful. If the solution is injected but hydrodissection is not seen one must worry that the needle may be intravascular. Often clinicians will aim for the “pocket” formed by the first rib inferiorly and the subclavian artery both medial and superiorly. Injecting most of the local anesthetic in this area will help to ensure that the inferior trunk is anesthetized to provide anesthesia to the distal arm. If simultaneously using a nerve stimulator, aim for hand motor stimulation around 0.5 mA. One study found that a stimulating current of 0.2 mA or less is reliable to detect intraneural placement of the needle while a current between 0.2 mA and 0.5 mA could not rule out intraneural position.[9] Once the needle is in proper position start to inject local anesthetic and watch for hydro dissection around the target nerves. Most clinicians use a volume between 25 and 40 mL of local anesthetic for this block. The effective volume in 50% of patients has been shown to be 23 mL while the effective volume in 95% of patients has been shown to be 42 mL.[10]

This approach is promoted by some as safer than the traditional lateral-to-medial approach because the inserted needle is pointing away from the subclavian artery and pleura. The difficulty in using this approach is that the subclavian artery can get in the way of blocking those “pocket” nerves to the distal arm.

With this approach the ultrasound probe is held in a more anterior-to-posterior angle than the traditional lateral-to-medial approach. It has the potential to provide better visualization of the brachial plexus as the plexus is located both lateral and posterior to the subclavian artery.

Clinical Pearls

- Given the close proximity of the brachial plexus to the lung at the supraclavicular level it is advisable to never advance the needle tip unless it is fully in view on the ultrasound image.

- Small arteries can appear hypoechoic and may be mistaken as the nerves of the brachial plexus. Use color Doppler to differentiate vascular structures from nerve structures.

- Using a smaller (5 cm) blocking needle can decrease the likelihood of inadvertent pleural puncture causing a pneumothorax.

Special Considerations

- Success rates with this block have been shown to be higher in patients with diabetes.[11] Some proposed explanations for this phenomenon have included: higher sensitivity of diabetic nerve fibers to local anesthetics and preexisting neuropathy associated with decreased sensation.

- Success rates have been shown to be lower in patients with a body mass index greater than 30 even when difficulty is anticipated and the block is performed by more senior physicians.[7]

- This block has been shown to be effective in children and to be able to be safely performed without causing pneumothorax in children 5 years of age or older.[12]

- Adjuncts such as midazolam and dexamethasone have been shown to shorten time to onset, prolong the duration of sensory and motor blockade, and improve postoperative analgesia when combined with local anesthetics for block of the brachial plexus.[13-15]

Complications

- Though now rare when ultrasound is used, the potential complication of a pneumothorax continues to be associated with the supraclavicular block. A study of 510 consecutive ultrasound guided supraclavicular blocks by operators of different skill levels showed no cases of clinically significant pneumothoraces were found.[2]

- Diaphragmatic hemiparesis occurs in approximately 50 to 67% of patients after this block.[16] This occurs because the phrenic nerve (C3-C5) lies in close proximity to the brachial plexus. Studies have shown that obese and other patients with compromised pulmonary reserve are most likely to poorly tolerate a transient phrenic nerve paralysis.[1] Though this complication is accepted by many clinicians as unavoidable some studies have shown that it can be avoided using ultrasound visualization and lower volumes of local anesthetic (20 mL).[16-17]

- The inferior trunk (ulnar nerve) can be missed when employing a supraclavicular approach to blocking the brachial plexus 30% of the time.[18]

- The supraclavicular approach to block the brachial plexus has been shown to be associated with a higher rate of Horner’s syndrome than the infraclavicular or axillary approach. This rate was reported at 37.5% in one study.[19]

- One of the most feared complication from any brachial plexus block is local anesthetic-induced cardiovascular collapse. This can occur from direct intravascular injection or simply high rates of vascular uptake. Intravenous intralipid infusion has shown utility in successful resuscitation of these patients.[20]

Summary

The supraclavicular block is a safe and simple technique for providing surgical or postoperative analgesia of the entire upper extremity from the level of the mid-humerus down to the hand. The introduction of ultrasound technology has greatly increased the popularity of the supraclavicular block as the ultrasound can be used to identify the brachial plexus, guide the needle into the plexus sheath, and evaluate the spread of local anesthetic while visually observing other important structures so as to avoid significant pneumothoraces and intravascular injection.

References

- Erickson JM, Louis DS, Naughton NN. Symptomatic phrenic nerve palsy after supraclavicular block in an obese man. Orthopedics 2009;32:386.

- Perlas A, Lobo G, Lo N, et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block: outcome of 510 consecutive cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:171-6.

- Tsui BC, Doyle K, Chu K, et al. Case series: ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block using a curvilinear probe in 104 day-case hand surgery patients. Can J Anaesth 2009;56:46-51.

- Williams SR, Chouinard P, Arcand G, et al. Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicular block. 2003, Anesth Analg 2003;97:1518-23.

- Lanz E, Theiss D, Jankovic D. The extent of blockade following various techniques of brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg 1983;62:55-8.

- Kapral S, Krafft P, Eibenberger K, et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach for regional anesthesia of the brachial plexus. Anesth Analg 1994;78:507-13.

- Franco CD, Gloss FJ, Vornov G, et al. Supraclavicular block in the obese population: an analysis of 2020 blocks. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1252-4.

- Beach ML, Sites BD, Gallagher JD. Use of a nerve stimulator does not improve the efficacy of ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks. J Clin Anesth 2006;18:580-4.

- Bigeleisen PE, Moayeri N, Groen GJ. Extraneural versus intraneural stimulation thresholds during ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block. Anesthesiology 2009;110:1235-43.

- Duggan E, El Beheiry H, Perlas A, et al. Minimum effective volume of local anesthetic for ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:215-8.

- Gebhard RE, Nielsen KC, Pietrobon R, et al. Diabetes mellitus, independent of body mass index, is associated with a "higher success" rate for supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:404-7.

- De Jose Maria B, Banus E, Navarro Egea M, et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular vs infraclavicular brachial plexus blocks in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2008;18:838-44.

- Jarbo K, Batra YK, Panda NB. Brachial plexus block with midazolam and bupivacaine improves analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2005;52:822-6

- Laiq N, Khan MN, Arif M, et al. Midazolam with bupivacaine for improving analgesia quality in brachial plexus block for upper limb surgeries. Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2008;18;674-8

- Shrestha BR, Maharjan SK, Tabedar S. Supraclavicular brachial plexus block with and without dexamethasone - a comparative study. Kathmandu Univ Med J, 2003;1:158-60.

- Renes SH, Spoormans HH, Gielen MJ, et al. Hemidiaphragmatic paresis can be avoided in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:595-9.

- Cornish PB, Leaper CJ, Nelson G, et al. Avoidance of phrenic nerve paresis during continuous supraclavicular regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2007;62:354-8.

- Fredrickson MJ. Speed of onset of 'coner pocket supraclavicular' and infraclavicular ultrasound guided brachial plexus block: a randomized observer-blinded comparison. Anaesthesia 2009;64:738-44.

- Tran de QH, Russo G, Munoz L, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary brachial plexus blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:366-71.

- Warren JA, Thoma RB, Georgescu A, et al. Intravenous lipid infusion in the successful resuscitation of local anesthetic-induced cardiovascular collapse after supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Anesth Analg 2008;106:1578-80.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top