Differentiating Brachial Plexopathy from Radiculopathy: A Problem-Based Learning Discussion

A 79-year-old male with a four-year history of persistent right arm pain was evaluated in the Pain Medicine Department. The pain started after a reverse shoulder arthroplasty and was reported as dull, throbbing, numbing, and shock-like, ranging from 5 to 8/10 on the visual analog scale (VAS). The pain was most severe at night, improved with rest, worsened with activity, and prevented him from performing his activities of daily living. He is a retired Navy aviator and had some trauma related to his military training.

In his medical history, he has diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, all well-controlled. He underwent previous surgical attempts for pain control, which included ulnar nerve release at the wrist and elbow (2017), anterior cervical discectomy and fusion C3-6 (2019), and wrist arthrodesis (2021), but none provided pain relief. He had attempted various conservative treatments, including physical therapy, desensitization techniques, and medical therapies such as gabapentin, pregabalin, and nortriptyline. Additionally, he underwent a temporary peripheral nerve stimulator implant of the ulnar nerve and received an ulnar nerve block, both without pain benefit.

On physical exam, the patient reported localized pain in the right superior lateral shoulder and scapular region radiating to the arm and digits (4th and 5th) in a C8-T1 distribution with associated numbness and paresthesia. The patient also demonstrated allodynia in the distribution of the axillary nerve and the ulnar nerve. He was areflexic with weakness and atrophy in the C8 and T1 innervated hand muscles and had limited range of motion in the right shoulder.

Questions

1. This patient mentioned a previous diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. What is cervical radiculopathy, its risk factors, and differential diagnoses?

Cervical radiculopathy (CR) is a nerve root dysfunction due to either compressive (cervical spondylitis and/or disc herniation) or non-degenerative causes (infections, injury, and neoplasia). It usually manifests as neck and arm pain, accompanied by disrupted sensation, motor strength, or reflex arc changes.1 Although CR is related to a single nerve root, it does not always follow a classic dermatome or myotome. Age is an important risk factor for cervical radiculopathy due to age-related degenerative changes, but previous trauma, prior lumbar radiculopathy, white race, and smoking have also been described as risk factors.2 Cervical radiculopathies can present with symptoms similar to peripheral mononeuropathies, such as tunnel carpal syndrome and ulnar entrapment. When a patient presents with neck and shoulder pain, myelopathy, brachial plexopathy (BP), shoulder impingement, and rotator cuff tears should also be considered. Cardiac pain, shingles, spinal abscess, meningitis, and malignancies are other differential diagnoses.1-3

2. During the physical exam, what tests and maneuvers can be performed to distinguish cervical radiculopathy from brachial plexopathy?

Symptoms of CR and BP can overlap with each other, and one of the difficulties when assessing pain is that it is a subjective symptom. Deep tendon reflexes, muscle strength, sensation, and range of motion should be assessed during the physical exam.1,2,4,5 Certain provocative tests, when positive, would favor a diagnosis of CR. Here is a brief review of them:

Upper limb neurodynamic test: consists of a series of passive movements in a specific order to provide progressive nerve tension. This test has variants for median, ulnar, and radial nerves. Considered as positive when pain is reported.

Spurling’s test: head compression with the patient placed in cervical extension combined with ipsilateral flexion. Considered as positive when pain into the ipsilateral/affected extremity is reproduced.

Shoulder abduction test: patient places the hand above the head in a sitting position. Considered as positive when pain is relieved.

Traction-distraction test: place the patient in supine position and apply axial traction force to the patient’s neck. Considered as positive with symptom improvement after traction and return of symptoms with the release of traction (distraction).

These tests have demonstrated a specificity range of 0.69 to 1.0.3,4 However, test execution may vary among examiners and thus can be related to a high risk of bias and different thresholds. This would explain the wide sensitivity range (0.38 - 0.97) with Spurling’s test. In clinical practice, clustering physical tests and complementary examinations could be a good alternative for increasing the likelihood of a diagnostic hypothesis.4

3. The patient’s magnetic resonance imaging reported normal appearance of the brachial plexus bilaterally. What other exam can be performed to characterize his condition better, and what would be the main differences between radiculopathy and plexopathy findings?

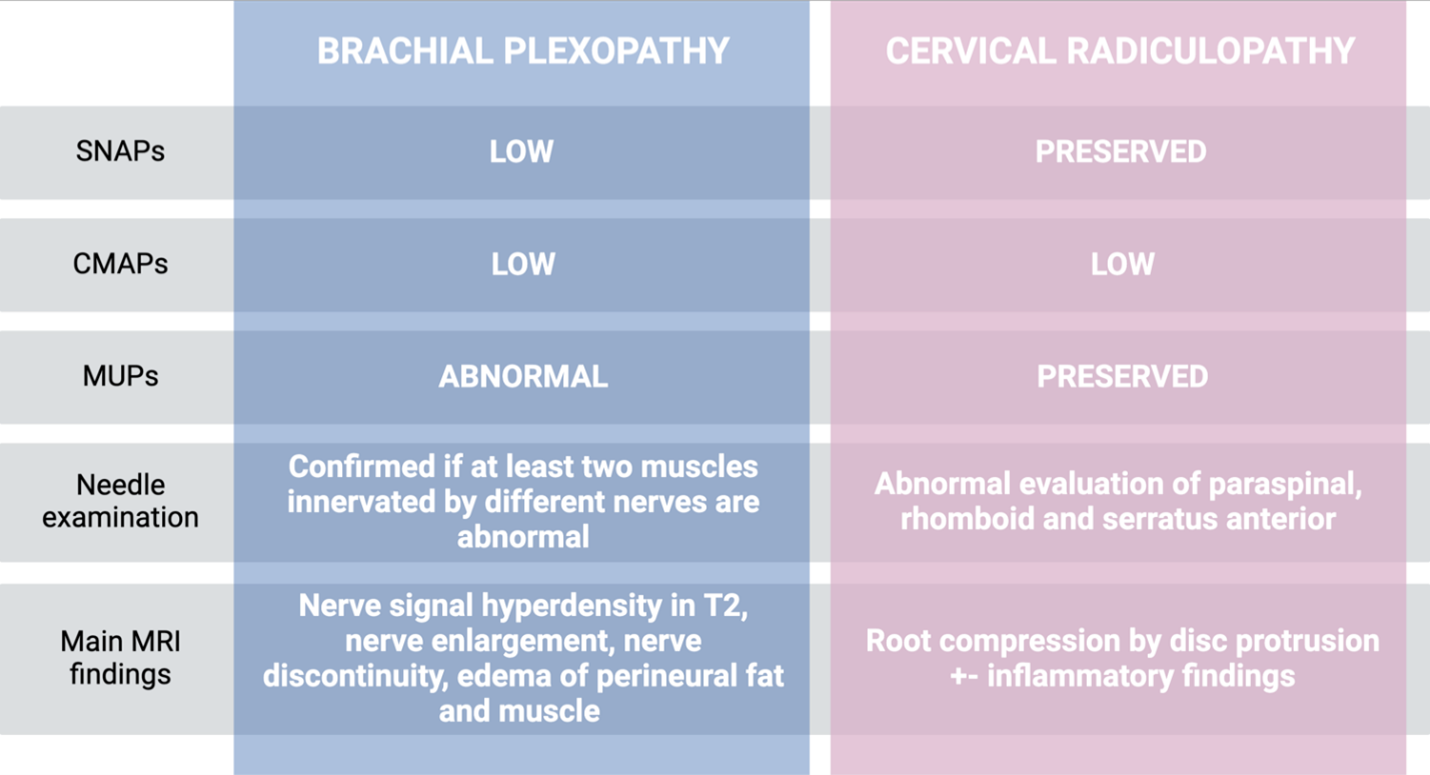

Normal imaging of the brachial plexus does not exclude injury or insult to the plexus. Electrodiagnostic studies are valuable tools for differentiating radiculopathies from plexopathies.6-10 These tests can provide evidence to help localize the lesion, identify affected segments, differentiate axonal loss from demyelination, define the severity of the nerve damage, and assess for evidence of reinnervation. Table 1 describes the main electrodiagnostic and MRI findings in both BP and CR.11 It is important to highlight that the findings may vary over time as the injury becomes more chronic, and early tests (performed within the first two to six weeks after symptom onset or injury) may be normal. Thus, performing these tests at least two weeks after injury is recommended.6,7,12 Electrodiagnostic exams can also be normal when symptoms are limited to sensory or pain without weakness.

In nerve conduction studies (NCS), sensory nerve action potentials (SNAP) are crucial in this differentiation because CRs are usually preganglionic and would present with preserved distal SNAPs. On the contrary, because BP affects distant fibers, they present with low distal SNAPs due to Wallerian degeneration of sensory axons. Low amplitude compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) are usually present in both CR and BP, but slow velocity and conduction blocks may suggest BPs, indicating demyelination.13,1

In electromyography (EMG), both CR and BP can present with fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves. However, adding cervical paraspinal muscles,6,13,14 rhomboid, and serratus anterior7 evaluation to the test increases its sensitivity because of their proximity to the nerve root. These muscles are usually affected in radiculopathies and spared in most plexopathies (excluding root avulsions), which can also present with abnormal motor unit potentials (MUP), indicating reinnervation.6,7 Our patient’s EMG evidenced a neurogenic process localized to the upper trunk of the brachial plexus and severe right ulnar neuropathy with slowed conduction velocities

4. The patient was diagnosed with brachial plexopathy, more specifically, brachial plexus avulsion injury. What is brachial plexopathy, and what are the current initial treatment options for this condition? How do they differ from cervical radiculopathy treatment?

Brachial plexopathy consists of damage to the brachial plexus and usually affects more than one nerve root. Symptoms will vary according to the injury mechanism and the degree of damage of the roots involved, but patients may present with muscle weakness, tingling sensation, neuropathic pain, and disability.10 Mild lesions may benefit from conservative treatment with rest, acute pain management, and physical therapy, recovering within months. However, more severe cases are treated with rehabilitation to prevent motion limitations by muscle atrophy or contractures, deformities, and disability. This is a multimodal approach with physical and occupational therapy, pain management (tricyclic anti-depressives, gabapentin or pregabalin, trials with opioids), and electric stimulation.5,9,15 First-line treatment in CR is similar to the initial approach in BP and includes physical therapy, cervical traction, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, opioids, and oral steroids in short courses.2,3,12

5. The patient’s pain did not respond to any conservative measure. What would you recommend next?

Surgical management in BP can be either immediate or delayed, depending on the injury mechanism and response to conservative treatment. The purpose is to regain useful or critical motor function such as tenodesis or pincer grasp through different techniques of nerve repairs and grafts, and muscle and tendon transfers. However, it has little effect on neuropathic pain secondary to root avulsion because of the complete tear from the spinal cord. Therefore, neuromodulation tools like spinal cord stimulators are valuable alternatives for refractory neuropathic pain.5,9,15

Persistent pain secondary to cervical radiculopathy may benefit from epidural steroid and local anesthetics injections and selective nerve root blocks. These minimally invasive interventions have shown effectiveness in providing pain relief over months and can be repeated depending on the dose administered, with significantly less risk of complications when compared to surgery.12,16 Still, around 25% of patients will undergo surgical treatment, with anterior cervical discectomy fusion as the gold standard procedure.2,16

After diagnosing brachial plexus avulsion, the patient underwent high-frequency (10 kHz) spinal cord stimulation trial and showed considerable improvement with 90% of pain relief during the trial. He ultimately underwent successful implant and at most recent follow-up reported that the pain no longer interfered with his sleep and had little interference with his activities. His average pain score showed consistent decrease. Importantly, had the diagnosis been made earlier in the patient’s treatment course, he may have been spared a number of surgeries that ultimately did not improve his symptoms.

Table 1: Main Electrodiagnostic and MRI Findings in Both BP and CR

References

1. Corey DL, Comeau D. Cervical radiculopathy. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98(4):791-xii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2014.04.001.

2. Woods BI, Hilibrand AS. Cervical radiculopathy: epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(5):E251-E259. https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0000000000000284.

4. Thoomes EJ, van Geest S, van der Windt DA, et al. Value of physical tests in diagnosing cervical radiculopathy: a systematic review. Spine J. 2018;18(1):179-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2017.08.241.

5. Smania N, Berto G, La Marchina E, et al. Rehabilitation of brachial plexus injuries in adults and children. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012;48(3):483-506.

6. Rubin DI. Brachial and lumbosacral plexopathies: A review. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2020;5:173-193. Published 2020 Aug 13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnp.2020.07.005.

7. Dhawan PS. Electrodiagnostic assessment of plexopathies. Neurol Clin. 2021;39(4):997-1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2021.06.006.

8.Gilcrease-Garcia BM, Deshmukh SD, Parsons MS. Anatomy, imaging, and pathologic conditions of the brachial plexus. Radiographics. 2020;40(6):1686-1714. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2020200012.

9. Noland SS, Bishop AT, Spinner RJ, Shin AY. Adult traumatic brachial plexus injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(19):705-716. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00433

0. Belviso I, Palermi S, Sacco AM, et al. Brachial plexus injuries in sport medicine: clinical evaluation, diagnostic approaches, treatment options, and rehabilitative interventions. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020;5(2):22. Published 2020 Mar 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk5020022.

11. Chhabra A, Thawait GK, Soldatos T, et al. High-resolution 3T MR neurography of the brachial plexus and its branches, with emphasis on 3D imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(3):486-497. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3287.

12. Manchikanti L, Knezevic NN, Navani A, et al. Epidural interventions in the management of chronic spinal pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) comprehensive evidence-based guidelines. Pain Physician. 2021;24(S1):S27-S208.

13. Dillingham TR, Annaswamy TM, Plastaras CT. Evaluation of persons with suspected lumbosacral and cervical radiculopathy: Electrodiagnostic assessment and implications for treatment and outcomes (Part I). Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(4):462-473. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26997.

14. Dillingham TR, Annaswamy TM, Plastaras CT. Evaluation of persons with suspected lumbosacral and cervical radiculopathy: Electrodiagnostic assessment and implications for treatment and outcomes (Part II). Muscle Nerve. 2020;62(4):474-484. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.27008.

15. Huang H, Chen S, Wu L, et al. Therapeutic strategies for brachial plexus injury. Folia Neuropathol. 2021;59(4):393-402. https://doi.org/10.5114/fn.2021.111996.

16. Mustafa R, Kissoon NR. Approach to radiculopathy. Semin Neurol. 2021;41(6):760-770. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1726363.