How I Do It: Ultrasound-Guided Quadratus Lumborum Block

Note: This article has been updated from its original publication in the ASRA News, Volume 15, Issue 4, pp. 34-40 (November, 2015). Revision date: February 6, 2022.

Introduction

Recently, the use of ultrasound for regional anesthesia has led to an up-surge in different interfascial plane blocks where the local anesthetics have been administered for effective surgical and postoperative pain management. Transversus abdominus plane (TAP) block is most studied or evaluated among all of these new procedures.

An ultrasound-guided approach as far posterior as the lateral border of the quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle has been described during a presentation by Dr. Blanco at the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy annual meeting in 2007 (unpublished work). In 2011, Carney et al.1 observed posterior spread of the contrast with the same approach technique and extension to the thoracic paravertebral space from the fifth thoracic vertebral level to the first lumbar vertebral level using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Subsequently, Børglum et al.2 described the transmuscular approach. With this approach, MRI studies showed the spread of local anesthetic cranially along the QL muscle reaching beyond the arcuate ligaments to the thoracic area.

QL blocks result in a wider sensory blockade compared to TAP block when performed using a similar volume of local anesthetic (T6-L1 for QL block vs. T10-T12 for the TAP block).2 Presumably, QL block also can involve the lateral cutaneous branches of the thoracoabdominal nerves (T6 to L1).3

The practice of QL block is gaining momentum; this article aims to describe the block technique and related, relevant sonoanatomy.

Indications for the use of quadratus lumborum block include:

- Exploratory laparotomy, large bowel resection, ileostomy, open/laparoscopic appendectomy, and cholecystectomy

- Cesarean section, total abdominal hysterectomy

- Open prostatectomy, renal transplant surgery, and nephrectomy

- Abdominoplasty and iliac crest bone graft

- Hip/orthopedic surgery

Midline incision requires bilateral blocks for adequate coverage.

Sonoanatomy

The QL muscle is part of the posterior abdominal wall dorsal to the iliopsoas muscle. It originates from the medial half of the iliac crest and inserts into the lower medial border of the 12th rib. It has four small tendineous insertions to the apices of the transverse processes of the upper four lumbar vertebrae. The ventral rami of the spinal nerve roots (including the subcostal and iliohypogastric nerves) pass between the QL and its anterior fascia. (Figure 1)

/elsharkawy_figure_1.jpg?sfvrsn=5997e4ed_2)

Figure 1. The Quadratus lumborum muscle in four views.

(a) QL muscle from the back covered by the erector spinae and latissmus dorsi muscles

(b) QL muscle from the back, ES, and LD muscles removed to show the origin and insertion of the QL muscle

(c) QL muscle from the front, on the left side the psoas muscle cut, showing the ventral rami of the spinal nerve roots pass in front of QL

(d) QL muscle cross section showing the surrounding muscles and its relation to the kidney

QL = quadratus lumborum; LD = latissmus dorsi; ES = erector spinae; TP = transverse process

When looking for the QL muscle with ultrasound, the tendons attached to the lumbar transverse process usually look like a small boat hooked to a stick, with the stick referring to tip of the transverse process, and water under the boat being the psoas muscle, which lies posterior to the QL. This view is typically seen when scanned at the level of a transverse process. When the ultrasound probe is between two adjacent processes, this view looks like the boat without the attached stick. The psoas muscle is usually hyperechoic at this level because of its intramuscular fibrous tendons. The QL muscle is surrounded by thick fibrous thoracolumbar fascia (TLF), usually hyperechoic. The transversalis fascia (TF) encases the transversus abdominis muscle and continues posterior medially, covering the anterior side of the investing fascia of the QL.

The TLF consists of both aponeurotic and fascial connective tissue. Its most important function is providing a retinaculum for paraspinal musculature in the lumbar region. It consists of three-layers: anterior, middle, and posterior. Using this three-layer model, the QL is situated anterior to the middle layer, separated from the psoas muscle by the anterior layer. The posterior and middle layers of the TLF fuse laterally to form the lateral raphe, which is a weave of connective tissue that joins with the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The middle layer of the TLF is multilayered (intermuscular septum) and medially attaches to the transverse processes of the vertebra.5-6 (Figure 2)

/elsharkawy_figure_2.jpg?sfvrsn=8f4cccc3_2)

Figure 2. The different layers of the thoracolumbar fascia.

In the thoracic and lumbar regions, the thoracic and lumbar paravertebral spaces of the fascial layers are continuous. This continuity occurs dorsal to the diaphragm through the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments and the aortic hiatus. This might be the presumed mechanism of spread of injectate cranially up to the thoracic paravertebral space and caudally.7 (Figure 3)

/elsharkawy_figure_3.jpg?sfvrsn=cdc2f765_2)

Figure 3. Sagittal section showing the fascial relations of the lower thoracic subendothoracic paravertebral space and the retroperitoneal space.

A number of vital structures are susceptible to possible injury and can make these blocks challenging; adequate care must be taken to understand their relative anatomy.

Kidney: Caution must be taken to avoid kidney injury. The lower pole of the kidney, which lies anterior to the QL muscle, will only be separated from the QL muscle by perinephric fat, the posterior layer of renal fascia, and the anterior layer of thoracolumbar fascia. (Figure 2)

Blood vessels: The four lumbar arteries arise from the aorta; they course posterior to the psoas major muscle. The abdominal branches of the lumbar arteries run laterally behind the QL muscle and then forward between the abdominal muscles. (Figure 4)

Peritoneum and bowels: Anterior to the anterior layer of the TLF, is a variable amount of fatty tissue, which forms a bed for the kidneys and the ascending and descending colon.

/elsharkawy_figure_4.jpg?sfvrsn=ac014ddc_2)

Figure 4: Cross-section of the QL muscle and its relation to the entral rami of the spinal nerve roots (yellow) and the abdominal branches of the lumbar arteries (red).

QL = quadratus lumborum

Patient Positioning and Equipment Selection

The lateral decubitus position is preferred over the supine position as it gives more exposure to the neuro axial structures and more stability in handling the ultrasound probe and needle. Additionally, patients are often more comfortable in this position. If possible, the hip is abducted and laterally flexed toward the same side of the block to contract the QL muscle. After sterile prepping and draping, low frequency (2-6 MHz) curved array ultrasound transducer is preferred to provide adequate penetration and visualize the three lateral abdominal muscle layers, the QL muscle, and the anatomy of the adjoining lumbar paravertebral area. This also may be a better option when a transmuscular approach is intended. The orientation marker is directed laterally for a transverse scan.

It is possible to perform the QL block in the supine position; however, visualization of the lumbar paravertebral area may be impaired.

Suggested Scanning Techniques for the Procedure

With the patient positioned in the lateral position, scanning is usually started at the mid-axillary line between the iliac crest and subcostal margin, moving the probe posteriorly until tapering of the three abdominal muscle layers and appearance of fascia transversalis and QL muscle is observed. The fascia transversalis usually appears as a hyperechoic layer, which forms a safe landmark to separate the muscle layers from the peri-nephric fat and the abdominal contents below the level of the lower pole of the kidney. Sometimes the bowel, kidney, and perinephric fat movements with breathing can be visualized underneath, making it helpful to make it a more definite landmark. (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Cross-section with the ultrasound probe location (a). Ultrasound image of the lateral abdominal wall (b).

QL = quadratus lumborum; ES = erector spinae; LD = latissimus dorsi; TP = transverse process; ATLF = anterior thoracolumbar fascia; MTLF = middle thoracolumbar fascia; EO = external oblique; IO = internal oblique; TA = transversus abdominus; PVS = paravertebral space.

Scanning also can be performed beginning posteriorly 4-5 cm lateral to the lumbar spinous process at the L3-4 level or higher. At this level, the transverse process of lumbar vertebrae, erector spinae muscle, psoas major muscle, and QL can be identified as a shamrock’s sign, as described by Børglum et al.8 (Figure 6)

/elsharkawy_figure_6.jpg?sfvrsn=5a6377a2_2)

Figure 6: Scanning technique to identify QL, psoas and ES muscles at the level of transverse process (top left, transverse process view) and between two transverse processes (bottom left, intertransverse process view) with correlating ultrasound images on the right.

AP = articular process; IF = intervertebral foramen; QL = quadratus lumborum; SS = sacrospinalis; TP = transverse process.

As described previously in the sonoanatomy section of this article, the outline of the QL can be seen in two different views: the oblique transverse view at the level of transverse process and at inter-transverse process view. The advantage of the inter-transverse view is the complete visualization of the psoas muscle by avoiding the acoustic shadow of the transverse process. The transducer may need to be slightly tilted medially to produce both of the above-mentioned views. The procedure can be done using either of these two views; however, it is suggested that doing the procedure with the transverse process in view may be better with the bone as an easy identifiable landmark making. It is also advisable to double check the other anatomical landmarks such as tapering transversus abdominis muscle, transverse process or lamina of the concerned vertebra, and vital organs like kidney and peritoneal folding, while scanning by moving the transducer from posterior to anterior and vice versa before finalizing the point of insertion of the needle.

Description of the Technique - The Needling Phase

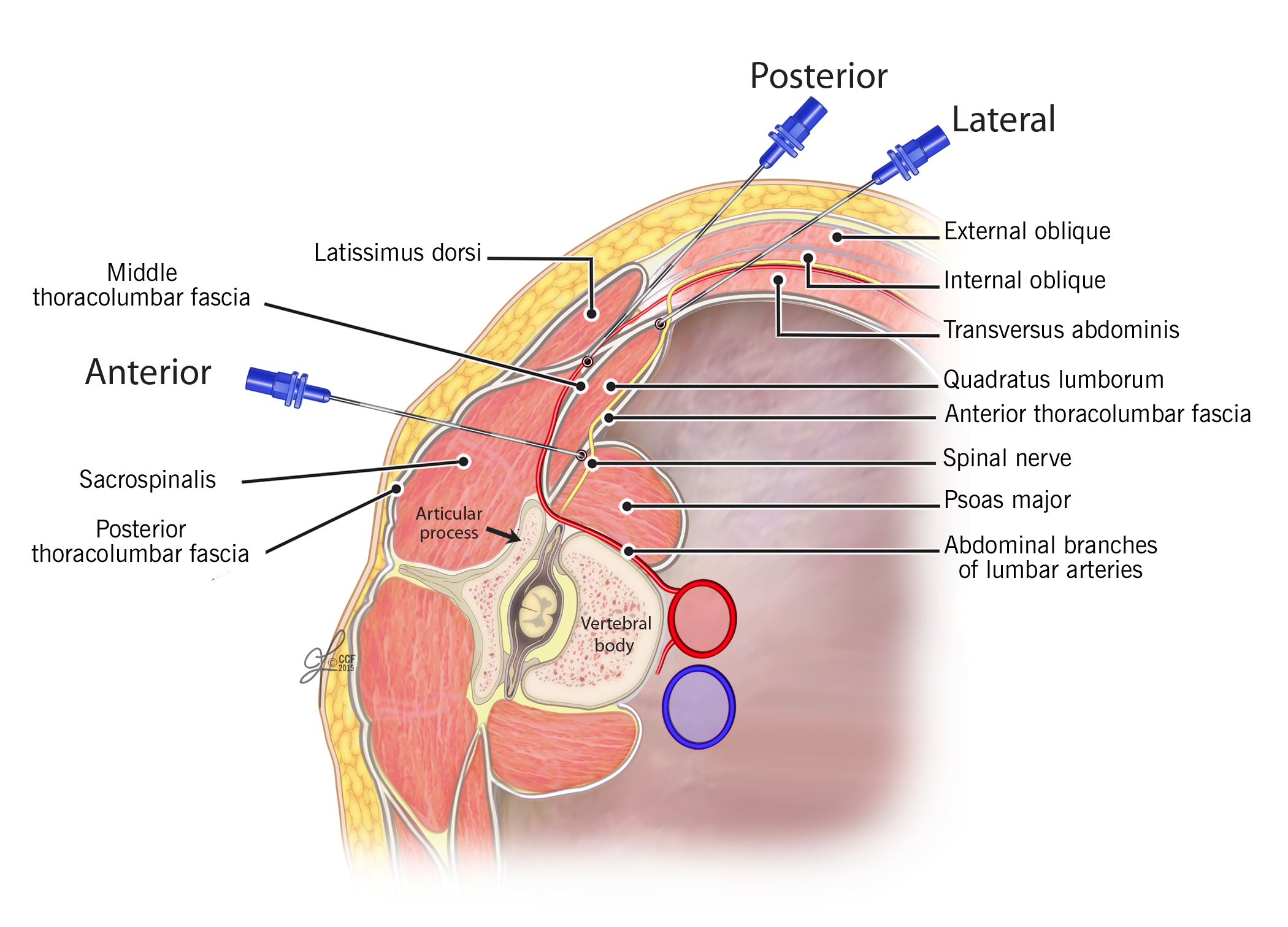

The QL block can be performed using three different approaches (Figure 7):

- The needle can be directed from anterior to posterior towards the junction of tapered abdominal muscle layers and QL muscle; local anesthetic will then be deposited in the anterolateral border of QL muscle at the junction with the transversalis fascia, outside the anterior layer of the TLF and superficial to the fascia transversalis. (Potential space medial to the abdominal wall muscles and lateral to QL muscle). (Lateral QL block, previously known as type 1)

- The needle can be advanced same as the first technique; however, local anesthetic can be deposited posterior to the QL muscle, between the QL muscle and the erector spinae, latissmus dorsi muscle, and serratus posterior inferior muscle outside the middle layer of the TLF. (Posterior QL block, previously known as type 2)

- Alternatively, the needle can be advanced from posterior to anterior through erector spinae muscle and QL (called as transmuscular approach by Børglum et al)2 to deposit the local anesthetic at the space between the fascial layers of the QL and psoas major muscles. The same results also can be achieved by directing the needle from anterior to posterior through the QL muscle. (Anterior QL block, previously known as type 3) Another option is with the subcostal oblique anterior approach; the needle insertion is caudal to the transducer, and the trajectory is in-plane, caudal–lateral to cranial–medial. The point of injection of local anesthetic lies in the tissue plane between the quadratus lumborum and psoas muscles. (Figure 9)

Figure 7. Illustrates the trajectory of needle for all three approaches of QL block (QLB1, QLB2, and QLB3).

Figure 8. Anterior quadratus lumborum block: subcostal approach. Parasagittal oblique transducer and caudal-to-cranial needle trajectory are shown. The external image and ultrasound images show the ultrasound probe position with an arrow indicating the needle trajectory.

ES,

erector spinae; PM, psoas major; QL, quadratus lumborum.

Which Type Is Better?

Limited data are available comparing the safety and efficacy of three types of QL block at this time. The optimal positioning of the needle tip and spread of the local anesthetic and their relative effects still needs to be investigated in larger studies.

Dose and Volume of Local Anesthetic

This “tissue/fascial plane” block requires a larger volume of local anesthetic to obtain a reliable block similar to other blocks of its kind. Volumes of 20-30 ml are usually recommended. The dose of local anesthetic is based on the size of the patient to ensure the maximum safe dose is not exceeded, especially with bilateral blocks. The block onset time depends on a number of factors including, but not limited to, vascularity of the area, the exact tissue plane where the local anesthetic was injected, type, and concentration of local anesthetic used. However, ultrasound-guided QL blocks seem to take a longer time for onset of effect compared to thoracic paravertebral block.8

Complications

Other than complications associated with any other peripheral nerve block procedures, complications related to this block are mainly due to faulty technical performance and lack of understanding of tissue plane anatomy. These might lead to inadvertent puncture of intra-abdominal structures like the kidneys, liver, and spleen. Extra caution should be taken especially for the right-sided block because the right kidney is slightly lower and smaller than the left seen under ultrasound.

Transient femoral nerve palsy after anterior QL block has been reported. In bilateral blocks with high-volume local anesthetic, systemic toxicity should be considered.

QL Block in the Anticoagulated Patient

The risks of bleeding complications are not known, and there are no specific recommendations. Due to the vascularity of the area, retroperitoneal spread of hematoma, proximity of the transmuscular approach to the paravertebral area, and the lumbar plexus, ASRA Pain Medicine guidelines should be considered in patients on anticoagulants who are receiving QL block either as a single shot or catheter. The risks versus benefits should be carefully considered.

Clinical Pearls

- Approximately, 2-3 cm lateral to the transverse process, the QL muscle usually thickens along with the thoracodorsal fascia, which appears thicker and relatively easier to be identified.

- Abduction and lateral flexion of the hip towards the same side of the muscle (the side to be blocked) allows ultrasound to more easily detect the QL muscle.

- During scanning, if the lower pole of the kidney, lower lobe of the liver, or spleen are visualized, the transducer needs to be moved more posterior and inferior.

- Use of color doppler is recommended before insertion of the needle during any approach to detect the abdominal branches of the lumbar arteries or any other vascular structure on the intended path of the needle.

- Other than the tactile feedback (pops) when encountering different fascial planes, visual confirmation using ultrasound and hydrodissection should be used appropriately due to complexity of the anatomical planes during performance of these blocks.

Conclusion

The available limited literature and experiences demonstrate that the QL block has the potential to produce sensory blockade and analgesia along lower thoracic and lumbar regions and can potentially be an alternative analgesic modality for selected abdominal surgeries. In addition to the characteristics of a TAP block, QL blocks have the potential to provide some visceral analgesia considering the spread to paravertebral space.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the contribution of Dr R. Blanco and Dr Vafi Salmasi to the work presented in this article and images.

All images are taken with permission from Cleveland Clinic art photography department.

Hesham Elsharkawy, MD, MBA, MSc, FASA, is an associate professor of anesthesiology at Case Western University in Cleveland, OH. He is also an anesthesiologist at MetroHealth Pain and Healing Center and the Outcomes Research Consortium at Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Carney J, Finnerty O, Rauf J, et al. Studies on the spread of local anaesthetic solution in transversus abdominis plane blocks. Anaesthesia 2011; 66:1023-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06855.x

- Børglum J, Jensen K, Moriggl B, et al. Ultrasound-guided transmuscular quadratus lumborum blockade. BJA: British J Anesth. 2013;111(Suppl.). https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/el_9919

- Elsharkawy H, El-Boghdadly K, Barrington M. Quadratus lumborum block: anatomical concepts, mechanisms, and techniques. Anesthesiology 2019; 130:322–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002524

- Uppal V, Retter S, Kehoe E, McKeen DM. Quadratus lumborum block for postoperative analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2020;67:1557-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01793-3.

- Skandalakis JE, Colborn GL, Weidman TA, et al. The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. Athens, Greece: Paschalidis Medical Publication Ltd.; 2004.

- Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, et al. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. J Anat. 2012;221:507–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x

- Karmakar MK, Gin T, Ho AM. Ipsilateral thoraco‐lumbar anaesthesia and paravertebral spread after low thoracic paravertebral injection. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:312–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/87.2.312

- Elsharkawy H, El-Boghdadly K, Barrington M. Quadratus lumborum block: anatomical concepts, mechanisms, and techniques. Anesthesiology 2019;130(2):322-35. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002524

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top