Curb Your Enthusiasm: Should Gabapentinoids Be a Routine Component of Multimodal Analgesia?

Cite as: Farhat B, Ip V, Sondekoppam RV. Curb your enthusiasm: should gabapentinoids be a routine component of multimodal analgesia?ASRA Pain Medicine News 2022;47. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra050122.015

Introduction

The concept of multimodal analgesia (MMA), wherein a multitude of analgesic drugs and techniques are used to target different pain pathways, has become the gold standard for managing postoperative pain over the last three decades. The practice of MMA is very relevant both as an opioid-sparing technique and also for enhanced recovery initiatives following surgery.1,2 While a variety of drugs (acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, opioids, alpha 2 agonists) and techniques (regional anesthesia, local anesthetic infiltration) have both the neurophysiological and clinical evidence for practice, gabapentinoids have been heavily scrutinized over the past few years for limited clinical efficacy.3-10 In this article, we provide an overview of the clinical pharmacology and evidence regarding the benefits and harms of gabapentinoids for acute pain management.

Historical Perspective

Gabapentin and pregabalin, both analogues of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), were initially approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1993 and marketed for complex partial seizures. Since then, they have been approved for other conditions such as postherpetic neuralgia (gabapentin and pregabalin) and diabetic neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury (pregabalin).11,12 Apart from the approved indications, gabapentinoids have been utilized for a multitude of off-label indications such as acute postoperative pain, migraine, restless leg syndrome, and substance dependence. Gabapentin is the sixth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, and up to 95% of the prescriptions are for off-label indications.13 Some of the reasons for its increased popularity are its low cost, lack of control of utilization at the federal level, and, more importantly, its perceived lack of addiction potential and benign adverse effect profile compared to opioids.14,15 Enthusiasm for gabapentinoids for analgesia is not only shared by anesthesiologists in the perioperative setting but also within institutional care pathways, with the hope of accelerating patient discharge after surgery.

Can Gabapentinoids Help for Postoperative Pain?

Gabapentinoids are purported to exert their analgesic effect through multiple mechanisms. They depress the sensitivity of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord by binding to the α2 δ-subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel and inhibiting their opening. This decreases the influx of calcium ions across the cell membranes and prevents the release of excitatory neurotransmitters (substance P and calcitonin gene–related peptide). They inhibit inflammatory mediators by activating the descending inhibitory pathways (primarily noradrenergic and serotoninergic). They also work by targeting the affective component of pain and modulating transmission of pain signals in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.9,16

Pharmacokinetically, both pregabalin and gabapentin have several similarities but differ in their absorption profile and bioavailability (Table 1).17 An interesting factor affecting clinical effects is that gut absorption seems to be the rate-limiting step for the systemic availability of gabapentin. The number of transporters in the gastrointestinal mucosa varies considerably between patients, and they are saturable, resulting in different temporal courses of plasma concentration following similar doses. Given this uncertainty, a typical regimen of gabapentin in an outpatient setting usually employs a slow dose titration over weeks for patients to have the desired clinical effect and minimize the risk of side effects in those with rapid absorption. Such a strategy may not be feasible in the perioperative arena, and higher initial doses have been routinely employed for MMA.

Table 1: Similarities and Differences Between Gabapentin and Pregabalin Pharmacokinetics17

Recommended Versus Proposed Dosing Regimens

The recommended dosing regimen for approved pain conditions compared to the proposed dosing for acute pain management is quite contrasting. In adults with postherpetic neuralgia, the FDA recommends starting gabapentin as a single, 300-mg oral dose on Day 1, and this is increased gradually up to 900 mg/day by Day 3.11 This dose can subsequently be titrated up to a maximum of 1,800 mg/day (600 mg, three times a day) for pain relief, as using doses greater than 1,800 mg/day as an additional benefit was not demonstrated. Such dose titration may not be possible when utilizing perioperative single-dose gabapentin (300-1,200 mg). There have been attempts to find the ideal dosing, duration, and timing of gabapentin in the perioperative period to augment acute postoperative analgesia. An excellent review on the dosing regimens of gabapentinoids for acute postoperative pain by Schmidt et al. summarized the available clinical evidence at the time of publication.9 They concluded that while preoperative dosing was marginally better than starting gabapentinoids postoperatively, the continuation of postoperative dosing was crucial for opioid sparing and analgesic benefits. Different doses and durations ranging from 300-1,500 mg for gabapentin and 75-300 mg for pregabalin over a few days to up to 2 weeks have been utilized in multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating their benefits for postoperative pain, but better evidence on ideal dosing regimens and duration is needed.9,18 One attempt to elucidate the ideal dosing regimen was made in the same review by Schmidt et al.,9 which concluded that the optimal preoperative dose of gabapentin or pregabalin in patients at risk for poor postoperative pain control should be 1,200 mg or 300 mg, respectively, and that such a dose should be given at least 2 hours before surgery (ideally the night before surgery). The authors have many cautions regarding this recommendation. Such dosing issues clearly highlight the contrasting strategies used to manage pain.

Is there any evidence supporting the use of gabapentinoids in acute pain management?

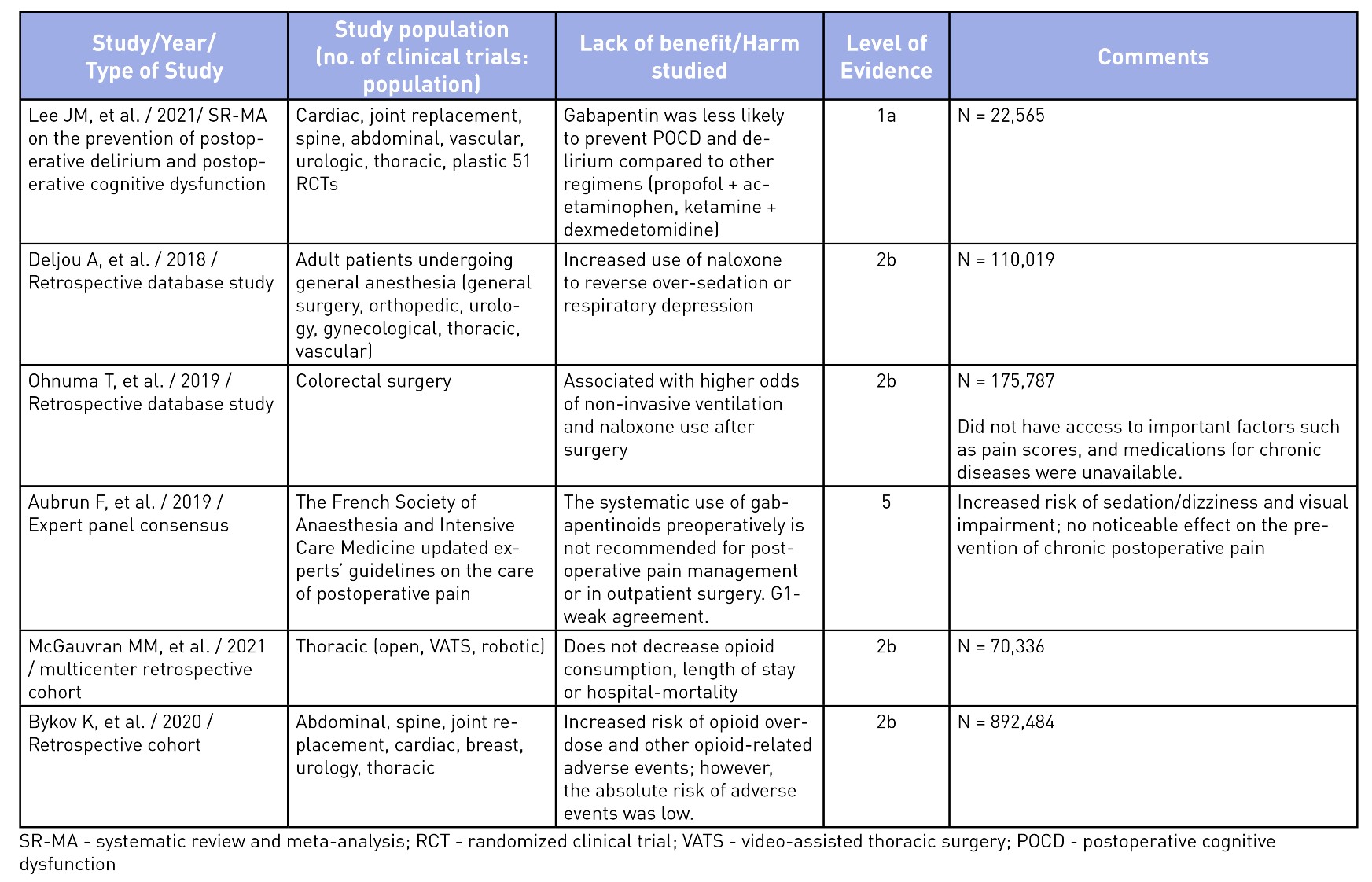

To elucidate the evidence for the use of gabapentinoids, an unstructured search was performed on Medline and the pertinent findings from seminal articles on analgesic benefits5,10,18-24 and harms25-30 have been summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The evidence of analgesic benefit has been weak and, at times, lacking for specific surgical populations such as total joint arthroplasties, obstetrical patients, or post-amputation pain control. Perhaps the highlighted benefits of gabapentinoids were initially founded on small-sample meta-analyses with minor benefits for an opioid-sparing effect. Larger meta-analysis have shown a recent decrease in enthusiasm toward its routine use.31 A similar sentiment has been explicitly stated in the French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine’s consensus guidelines, which states that gabapentinoids should not be used routinely for outpatient surgery.25 Other opioid-sparing modalities, such as acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesia, dexmedetomidine (alpha-2 agonists), ketamine (NMDA antagonists), and regional anesthesia, have better evidence for their incorporation into MMA regimens and should be considered.1 The mode of actions and evidence for the use of other MMA medications are beyond the scope of this article.

Table 2: Summary of Seminal Articles on the Use of Gabapentinoids for Postoperative Pain Control

Table 3: Evidence of Harm or Lack of Non-Analgesic Benefits of Gabapentinoids

Are there any risks of increased adverse events with their routine use?

Well-documented, albeit often overlooked, adverse effects from gabapentinoids include dizziness, sedation, somnolence, ataxia, blurred vision, weight gain, abuse, respiratory depression, and fatigue.14,17,26,30,32 Of these, the latter two are significant, especially in the elderly population or those with concurrent use of opioids and other sedatives.14,26,30,32 Recent evidence does not support the benefit of gabapentinoids in reducing postoperative delirium, thus debunking this previously held myth regarding their non-analgesic benefit.28,32

Serious side effects have been reported in recent trials where the use of gabapentinoids have shown an increased odds of postoperative pulmonary complications (respiratory failure, pneumonia, reintubation, pulmonary edema, noninvasive ventilation, or invasive mechanical ventilation) and intensive care unit admission (up to six-fold greater) in patients undergoing thoracic surgery30 and at increased risk of opioid-related adverse events.24 While not particularly related to their perioperative use, the abuse of gabapentinoids has been increasingly reported in recent years, which can be of concern to prescribers.14 Given the plethora of possible adverse events, the American Geriatrics Society has listed gabapentin as a potentially inappropriate medication combination for older adults taking opioids due to an increased risk of opioid overdose and sedation-related adverse events.33 There are several questions that still remain unanswered regarding the relevance of gabapentinoids for acute postoperative pain. Is there a benefit of slow escalating dosing regimen started a few days to weeks ahead of the planned surgery? Is pregabalin better than gabapentin as it has reliable bioavailability with escalating doses and may translate to better analgesic benefits? Is there a role for gabapentinoids in specific surgical populations such as spine surgery, amputations, and joint surgeries where postoperative pain is significant? Can they be of benefit in patients with hyperalgesia or in those with pain hypersensitivity states? While we await better evidence on the safety and efficacy in specific surgical populations, routine use of gabapentinoids is no longer acceptable in patients at risk of serious adverse events (extremes of age, high risk behavior, polypharmacy). We believe that the appropriate use of gabapentinoids should be based on a risk/benefit assessment on a case-by-case basis, using the lowest effective dose, titrated gradually.34 It should be noted that a reduced dose regimen should be used for patients with renal impairment, since both gabapentin and pregabalin are primarily excreted renally without undergoing metabolism.

Conclusion

The increasing demand and prescribing of gabapentinoids for its use in acute pain management has paralleled its off-label uses in other specialties in medicine. Recent evidence from systematic reviews with large sample sizes demonstrated a rather different landscape for gabapentinoids in its perioperative use. With little clinical benefits and potentially significant adverse effects that cannot be ignored, especially in the elderly population, its use for perioperative acute pain management is questionable. The current evidence does not support routine perioperative use of gabapentinoids for acute postoperative pain management, especially in same-day surgical patients. This is due to their minimal analgesic benefits along with increasing evidence regarding adverse effects or abuse. Perhaps it is time we curb our enthusiasm on the off-label use of gabapentinoids while we await better quality evidence on specific postoperative pain scenarios.

Bassam Farhat, MD, is a regional anesthesia and acute pain fellow in the department of Anesthesia at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

Vivian Ip, MB, ChB, FRCA, is an associate clinical professor in the department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Rakesh V. Sondekoppam, MBBS, MD, is a clinical associate professor in the department of Anesthesia at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

References

- Helander EM, Menard BL, Harmon CM et al. Multimodal analgesia, current concepts, and acute pain considerations. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2017;21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-017-0607-y

- Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL. Postoperative multimodal analgesia pain management with nonopioid analgesics and techniques: a review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:691-7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0898

- Carley ME, Chaparro LE, Choiniere M, et al. Pharmacotherapy for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery in adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2021;135:304-25. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003837

- Clarke H, Bonin RP, Orser BA, et al. The prevention of chronic postsurgical pain using gabapentin and pregabalin: a combined systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2012;115:428-42. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318249d36e

- Dahl JB, Mathiesen O, Møiniche S. 'Protective premedication': an option with gabapentin and related drugs? A review of gabapentin and pregabalin in in the treatment of post-operative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:1130-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00484.x

- Go BC, Go CC, Chorath K, Moreira A, Rajasekaran K. Multimodal analgesia in head and neck free flap reconstruction: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;1945998211032910. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211032910

- Huang F, Yang Z, Su Z, Gao X. The analgesic evaluation of gabapentin for arthroscopy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100(20):e25740. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000025740

- Rasmussen ML, Mathiesen O, Dierking G, et al. Multimodal analgesia with gabapentin, ketamine and dexamethasone in combination with paracetamol and ketorolac after hip arthroplasty: a preliminary study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010;27(4):324-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e328331c71d

- Schmidt PC, Ruchelli G, Mackey SC, Carroll IR. Perioperative gabapentinoids: choice of agent, dose, timing, and effects on chronic postsurgical pain. Anesthesiology 2013;119(5):1215-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a9a896

- Tiippana EM, Hamunen K, Kontinen VK, Kalso E. Do surgical patients benefit from perioperative gabapentin/pregabalin? A systematic review of efficacy and safety. Anesth Analg 2007;104(6):1545-56. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000261517.27532.80

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Neurontin® (gabapentin) Capsules, Neurontin (gabapentin) Tablets, Neurontin (gabapentin) Oral Solution. Published 3/1/2011. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/020235s036,020882s022,021129s022lbl.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2022.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Lyrica medication guide, 5/2018. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021446s035,022488s013lbl.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2022.

- GoodRx. Top 10 Prescription Medications in the U.S. (November 2021). Available at: https://www.goodrx.com/drug-guide. Accessed April 5, 2022.

- Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR. Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin. Drugs 2017; 77(4):403-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0700-x

- Peckham AM, Evoy KE, Och L, et al. Gabapentin for off-label use: evidence-based or cause for concern? Subst Abuse 2018;12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221818801311

- Chincholkar, M. Analgesic mechanisms of gabapentinoids and effects in experimental pain models: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth 2018;120(6):1315-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.02.066

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet 2010;49(10):661-9. https://doi.org/10.2165/11536200-000000000-00000

- Verret M, Lauzier F, Zarychanski R, et al. Perioperative use of gabapentinoids for the management of postoperative acute pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2020;133(2):265-79. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003428

- Felder L, Saccone G, Scuotto S, et al. Perioperative gabapentin and post cesarean pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;233:98-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.11.026

- Mao Y, Wu L, Ding W.The efficacy of preoperative gabapentin in spinal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician 2017;20(7):649-61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1231-4

- Hannon CP, Fillingham YA, Browne JA, et al. The efficacy and safety of gabapentinoids in total joint arthroplasty: systematic review and direct meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2020;35(10):2730-8.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.05.033

- Jiang Y, Li J, Lin H, et al. The efficacy of gabapentin in reducing pain intensity and morphine consumption after breast cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(38):e11581. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000011581

- Kang J, Zhao Z, Lv J, et al. The efficacy of perioperative gabapentin for the treatment of postoperative pain following total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2020;15(1):332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01849-6

- Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Kramp S, et al. A randomized study of the effects of gabapentin on postamputation pain. Anesthesiology 2006;105(5):1008-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200611000-00023

- Aubrun F, Nouette-Gaulain K, Fletcher D, et al. Revision of expert panel's guidelines on postoperative pain management. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2019;38(4):405-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2019.02.011

- Bykov K, Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Vine SM, Patorno E. Association of gabapentinoids with the risk of opioid-related adverse events in surgical patients in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2031647. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31647

- Deljou A, Hedrick SJ, Portner ER, et al. Pattern of perioperative gabapentinoid use and risk for postoperative naloxone administration. Br J Anaesth 2018;120(4):798-806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.113

- Lee JM, Cho YJ, Ahn EJ, Choi GJ, Kang H. Pharmacological strategies to prevent postoperative delirium: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul) 2021;16(1):28-48. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.20079

- McGauvran MM, Ohnuma T, Rahunathan K, et al. Association between gabapentinoids and postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing thoracic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021; 8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2021.10.003

- Ohnuma T, Krishnamoorthy V, Ellis A, et al. Association ‘between gabapentinoids on the day of colorectal surgery and adverse postoperative respiratory outcomes. Ann Surg 2019;270(6):e65-e7. https://doi.org/0.1097/SLA.0000000000003317

- Kharasch E, Clark J, Kheterpal S. Perioperative gabapentinoids: deflating the bubble. Anesthesiology 2020;133(2):251-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003394

- Gupta A, Joshi P, Bhattacharya G, et al. Is there evidence for using anticonvulsants in the prevention and/or treatment of delirium among older adults? Int Psychogeriatr 2021;24:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221000235

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

- Kumar AH, Habib AS. The role of gabapentinoids in acute and chronic pain after surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2019;32(5):629-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000767