How I Do It: Phrenic Sparing Shoulder Block

Cite as: Rayaz H, Newton J, Siu E. How I do it: phrenic sparing shoulder block. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2025;50. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110125.014.

How I Do It

Introduction

The interscalene nerve block is the mainstay of perioperative analgesia for shoulder surgery.1 It is effective as it covers nerve roots C5 and C6 of the brachial plexus that contribute to the innervation of the shoulder capsule, muscles, proximal humerus, scapula, and cutaneous sensation. However, performing this block often results in ipsilateral phrenic nerve blockade as the phrenic nerve, and the nerve root fascicles that contribute to it, are in proximity to the nerve roots targeted during the block. Most patients tolerate the resulting diaphragmatic hemiparesis, but the patient may experience a 30% decrease in vital capacity, which may not be tolerated by certain patient populations. This has led to the exploration of phrenic nerve-sparing blocks, such as the more selective suprascapular and axillary nerve blocks.2

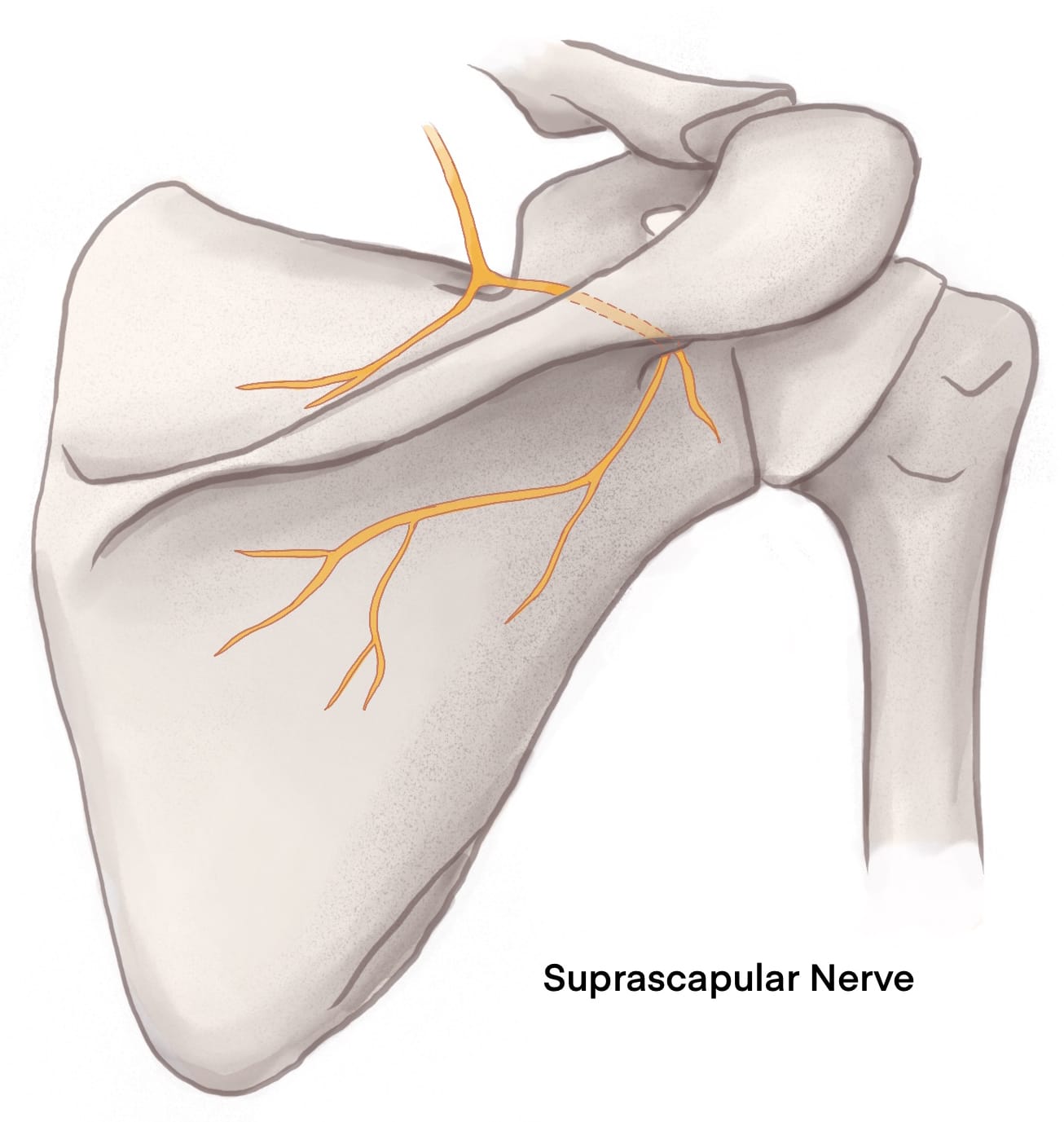

Anatomy

The suprascapular nerve (from C5 and C6 nerve roots) leaves the anterior neck area by running posteriorly to the suprascapular notch with the omohyoid muscle. From here, it traverses the superior transverse scapular ligament through the suprascapular notch, continuing to run deep to the supraspinatus to the spinoglenoid notch before moving towards the shoulder capsule.3

Then, there’s the anatomy behind the selective axillary nerve block. The term “selective” is used here to distinguish this block from the axillary brachial plexus block. The axillary nerve branches off the posterior cord of the brachial plexus, travels through the axilla, and then wraps around the humeral neck and continues to innervate the deltoid muscle, teres minor muscle, and superolateral cutaneous aspects of the shoulder.4

The subscapular, musculocutaneous, and lateral pectoral nerves are also involved in the innervation of the shoulder. These nerves, plus the axillary nerve, can be blocked with the infraclavicular brachial plexus block.5 The infraclavicular brachial plexus block does not pose a significant risk to blocking the phrenic nerve, so a combination of a suprascapular nerve block and an infraclavicular brachial plexus block would cover much of the shoulder. The downside is that this approach would block much of the arm distal to the shoulder. Also, the suprascapular and selective axillary nerve block combination is quite successful without affecting the arm distal to the shoulder, coming close to even if not fully reaching interscalene levels of postoperative pain control.6 The rest of this article will focus on this suprascapular and selective axillary nerve block combination as the infraclavicular brachial plexus block has been well described elsewhere.6

The posterior approach to the suprascapular nerve block may be preferred to avoid the phrenic nerve completely. There is an anterior approach to the suprascapular nerve block that is still essentially at the level of the supraclavicular block and can thus risk spread to the phrenic nerve.6

By becoming proficient in utilizing this combination of nerve blocks, this option can be offered to higher-risk pulmonary patients for perioperative analgesia.

Patient Selection

Patient selection is important because phrenic sparing blocks are good analgesic blocks but still not quite as good as the interscalene block in the immediate postoperative period.8 By deciding to pursue these blocks over an interscalene approach to brachial plexus blockade, one must weigh the potentially decreased analgesic benefit against the risk of phrenic nerve blockade. If the patient can tolerate phrenic nerve blockade, administering an interscalene block would be advisable.

When evaluating a patient for an interscalene block, assess the baseline respiratory status. If the patient requires supplemental oxygen for normal daily activities, for example, consider phrenic-sparing blocks. There may also be a concern that if these blocks are not as effective as an interscalene block, there is the risk of giving a patient with compromised pulmonary function a higher dose of opioids in the immediate postoperative setting (compared to patients receiving interscalene nerve blocks). This comes down to clinical decision-making and the patient's condition, which can be a difficult judgment call. Phrenic-sparing blocks may be the best option in this case because phrenic nerve paralysis from an interscalene block could result in undesired sequelae, such as urgent or prolonged intubation, unplanned hospital admission, etc.

How I Do It: Phrenic Sparing Shoulder Blocks

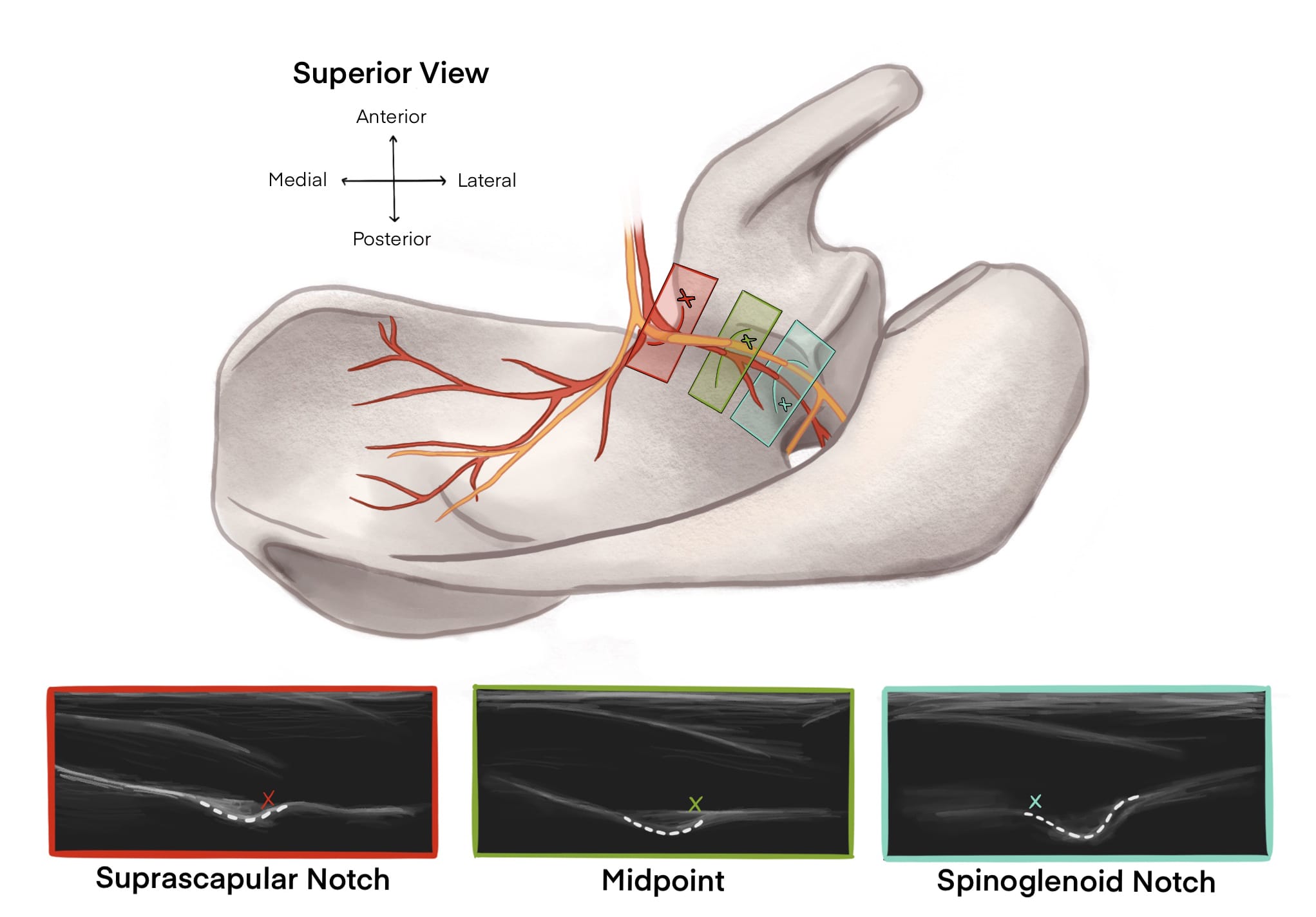

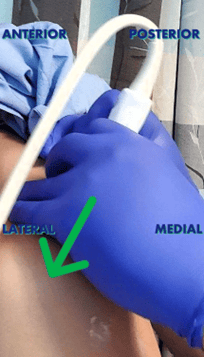

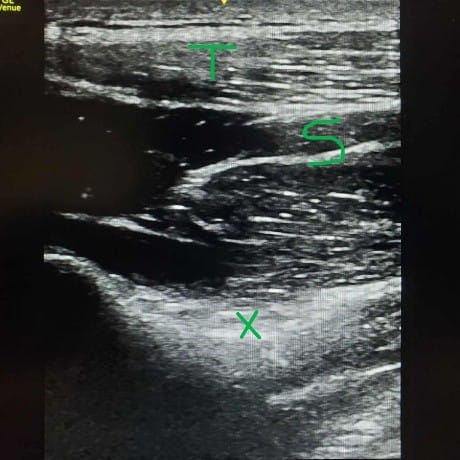

For the posterior suprascapular nerve block, ask patients to sit up on the side of the bed, reach across their chests, and put their hands on their contralateral shoulder. This position pushes out the scapula posterolaterally. The ultrasound probe is positioned just anterior to the spine of the scapula and scanned in a medial to lateral direction (still following along with the spine of the scapula) to locate the spinoglenoid notch that contains the suprascapular nerve and artery. If the probe is angled too far anteriorly, the suprascapular notch with the suprascapular nerve and artery traversing the superior transverse scapular ligament will be visualized. While the block can be done here, it is risky to do so. The chest wall is just anterior to this location, and the risk of a potential pneumothorax in patients with severe pulmonary disease would be problematic. Instead, maintain a steep angle with the probe “looking down” into the patient. This allows the operator to visualize the relatively posterior and inferior spinoglenoid notch, which is a safer but still effective injection site. Insert the needle in-plane, medial-to-lateral. After the suprascapular artery has been identified on color and successfully avoided, inject 10ml of local anesthetic next to the suprascapular nerve.9 Keep in mind that this is a nerve with motor as well as sensory function, so be careful about how close the needle is to the nerve. A nerve stimulator can be used in conjunction with ultrasound to identify nerves that are difficult to visualize on ultrasound. Look for muscle twitch in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles if using a nerve stimulator. The needle can land on bone medial to the nerve, spread local anesthetic deep into the supraspinatus muscle towards the nerve, and still achieve a successful block.10

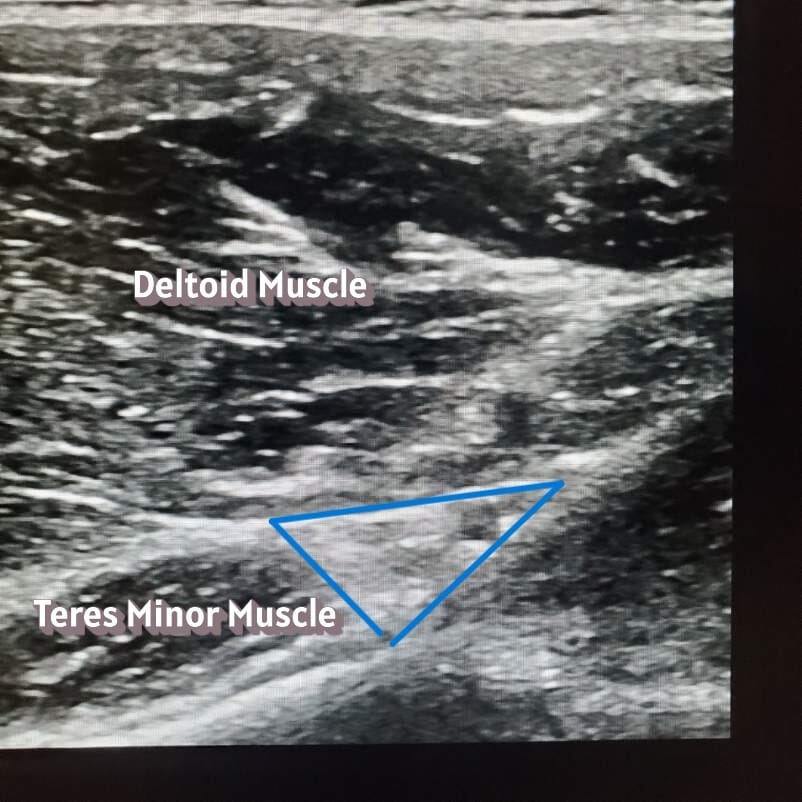

Now on to the selective axillary nerve block. Keep patients in the same sitting position, but now have them let go of the contralateral shoulder and relax their arm by their side. Place the probe in the sagittal position on the posterolateral side of the humeral head. After locating the head of the humerus, scan caudad to the transition between the humeral metaphysis and diaphysis. As the straight line of diaphysis now curves into the metaphysis, put the color setting on the ultrasound machine and identify the posterior circumflex humeral artery and the small axillary nerve running in the fascial compartment between teres minor and the deltoid muscles.11 Just like in the approach to the suprascapular nerve, a nerve stimulator can help to identify an axillary nerve that is difficult to visualize on ultrasound. Look for a deltoid and/or teres minor twitch if using a nerve stimulator. Place 10 ml of local anesthetic into or deep to the fascial compartment containing the axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery. The nerve is not always visible, so identifying the bony, muscle, fascial, and arterial landmarks is important. Injecting into or deep into the fascial compartment containing the nerve is sufficient to block this nerve. The injection doesn’t need to be immediately adjacent to the nerve. If the nerve isn’t visualized, it’s advisable to inject deep into the fascial compartment where the shaft of the humerus transitions to the head of the humerus to avoid nerve injury.

Conclusion

You can look forward to having a relatively comfortable patient whose pulmonary function is at or close to baseline postoperatively. By becoming proficient in utilizing this combination of nerve blocks, this option can be offered to higher-risk pulmonary patients for perioperative analgesia.12

References

- Kokatnur L, Rudrappa M. Diaphragmatic palsy. Diseases 2018;6(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases6010016

- Feigl GC, Litz RJ, Marhofer P. Anatomy of the brachial plexus and its implications for daily clinical practice: regional anesthesia is applied anatomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2020;45(8):620-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-101435

- Wang J, Halling B, Hult D,et al. Suprascapular nerve anatomy and its implication for approaches to peripheral nerve stimulation of its sensory branching: a morphometric cadaveric study. Surg Radiol Anat2025;47(1):181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-025-03692-y

- Gurushantappa PK, Kuppasad S. Anatomy of axillary nerve and its clinical importance: a cadaveric study. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9(3):AC13-7. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/12349.5680

- Aszmann OC, Dellon AL, Birely BT, et al. Innervation of the human shoulder joint and its implications for surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;(330):202-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-199609000-00027

- Diwan S, Sathe D, Sabnis A, et al. Pathway from anterior suprascapular nerve block to the phrenic nerve: a cadaveric dye study. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2025;20(2):175-82. https://doi.org/10.17085/apm.24142

- Sandhu NS, Capan LM. Ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth2002;89(2):254-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aef186

- Hussain N, Goldar G, Ragina N, et al. Suprascapular and interscalene nerve block for shoulder surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2017;127(6):998-1013. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001894

- Peng PW, Wiley MJ, Liang J, et al. Ultrasound-guided suprascapular nerve block: a correlation with fluoroscopic and cadaveric findings. Can J Anaesth 2010;57(2):143-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-009-9234-3

- Girón-Arango L, Perlas A. Surgical anesthesia for proximal arm surgery in the awake patient. Reg Anesth Pain Med 202;46(5):446-51. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-101929

- Saravanan R, Nivedita K, Karthik K. Selective suprascapular and axillary nerve (SSAX) block - a diaphragm sparing regional anesthetic technique for shoulder surgeries: a case series. Saudi J Anaesth2022;16(4):457-9. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.sja_782_21

- Neuts A, Stessel B, Wouters PF, et al. Selective suprascapular and axillary nerve block versus interscalene plexus block for pain control after arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a noninferiority randomized parallel-controlled clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018;43(7):738-44. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000777