Understanding Neuroplastic Pain: Clinical Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

Cite as: Gou C, Metzler J. Understanding neuroplastic pain: clinical implications for diagnosis and treatment. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2026;51. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020126.010.

Pain physicians are generally skilled at treating focal pain syndromes arising from identifiable pathologies, such as fractures, malignancies, or nerve compression. However, patients with pain that does not correspond to expected disease or injury patterns, or that does not respond to conventional therapies, remain a major challenge for both clinicians and patients. In these cases, there is a risk of discounting the patient’s experience. Developing a scientific framework for understanding such conditions is essential to broaden the differential diagnosis, improve diagnostic accuracy, and provide effective care.

It is intuitive to conceptualize pain as arising directly from tissue damage. This view is reinforced by daily experiences with injury and by biomedical models of pain diagnoses. However, multiple clinical and experimental observations demonstrate that pain and tissue damage can occur independently. A well-known case report described a construction worker who experienced severe pain when a nail penetrated his boot. His pain was so intense that he required narcotics and sedation until it was discovered that the nail had gone between his toes and not pierced his foot.1 Conversely, soldiers in battle have been observed to sustain significant injuries and yet report little or no pain in the moment.

This underscores the importance of distinguishing between nociception and pain:

- Nociception refers to activity in primary afferent neurons and their central projections, typically in response to noxious stimuli and tissue breakdown.

- Pain, according to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”2

Basic science confirms the separation between these phenomena. Nociceptor activation does not reliably predict the onset of pain,3 firing rate does not correlate with pain intensity,4 and the degree of tissue damage does not determine nociceptor activity.4,5

Clinically, it is useful to distinguish between:

- Secondary pain, arising from definable pathology such as fracture, malignancy, or nerve injury.

- Primary pain, persisting in the absence of ongoing tissue damage.

While secondary pain is generally amenable to established interventions, primary pain remains a significant therapeutic challenge.

Primary Pain Terminology

Primary pain has been described using several overlapping terms, including nociplastic pain, central sensitization, and neuroplastic pain. These concepts recognize altered central nervous system processing, particularly in the modulation and amplification of pain signals, and often describe a similar clinical phenotype characterized by widespread pain, hyperalgesia, and/or allodynia.

These terms differ in their emphasis on distinct aspects of pain biology. Nociplastic pain is the formal clinical descriptor for pain arising from altered nociception in the absence of clear evidence of ongoing tissue damage or somatosensory system disease.6 It was introduced by the IASP as a third mechanistic pain category, alongside nociceptive and neuropathic pain.6 Central sensitization refers to the underlying neurophysiological processes commonly observed in nociplastic pain states, including enhanced pain signal amplification and impaired endogenous pain inhibition across multiple levels of the nervous system.6 Neuroplastic pain highlights the role of maladaptive neural plasticity and emphasizes the structural and functional changes within the brain and spinal cord that contribute to the persistence of chronic pain. Given the role of neuroplasticity in both the development and reversal of primary pain, as described below, this article will use the term neuroplastic pain to refer to primary pain conditions.

Brain-Generated Sensations Demonstrated by the Rubber Hand Illusion

Pain, whether primary or secondary, is an output of the brain, evolved to warn and protect, but with primary pain, this system can become maladaptive, generating persistent pain without ongoing tissue damage.

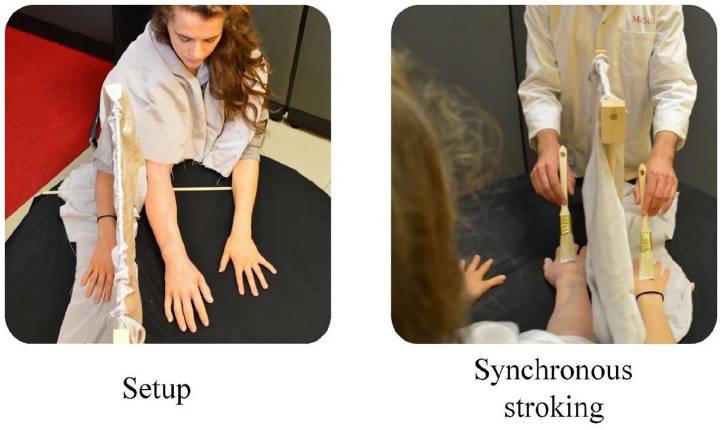

This power of the human brain to generate pain is illustrated by the rubber hand illusion,7,8 in which a participant’s hidden real hand and a visible rubber hand are stroked synchronously. After a period, stroking of the real hand ceases while the rubber hand continues; yet participants often report that their real hand still feels touched. This demonstrates how the brain integrates visual and tactile cues to create real —but inaccurate—sensory experiences.7,8 Similarly, in primary pain, the brain’s interpretation of threat or tissue damage can become decoupled from actual injury, producing real pain despite no ongoing nociceptive input. A video demonstration of the rubber hand illusion can be viewed online. 9

Left: experimental setup with a fake silicon arm between two real hands and the occluder. Right: participant view during synchronous stroking.

Neuroplastic pain often begins with acute injury and nociception. Emotional responses, such as fear, anxiety, and vigilance, are adaptive in the acute setting but may persist after tissue healing and become maladaptive. Through associative learning, fear and anxiety can become subconsciously linked with pain, creating a self-reinforcing loop (“neurons that fire together wire together”).

It is intuitive to conceptualize pain as arising directly from tissue damage. This view is reinforced by daily experiences with injury and by biomedical models of pain diagnoses.

Neuroimaging Evidence

Functional MRI provides compelling evidence of this process. Similar patterns of brain activity occur with thermal stimulation and during hypnotic suggestion.10 Patients with acute back pain demonstrate activity in nociceptive regions, whereas those with chronic back pain show activity confined to emotion-related circuitry.11 Longitudinal studies reveal that patients who recover from acute back pain exhibit diminished overall brain activity, whereas those who develop persistent pain show reduced activity in nociceptive regions and increased activity in emotional circuits.11 Moreover, studies comparing physical pain with social rejection have demonstrated overlapping neural networks, reinforcing the close relationship between pain and emotion.12

Clinical Application

Given the role of brain and emotion circuits in neuroplastic pain, patient education is critical. Patients’ understanding of the mechanisms sustaining their pain is central to recovery as the same neuroplasticity that perpetuates chronic pain can also be harnessed for healing.

The clinical task is to:

- Demonstrate how the mechanisms behind neuroplastic pain apply to the individual patient.

- Help patients decouple pain from fear and anxiety.

- Identify emotional triggers, past or ongoing, that perpetuate pain.

- Use graded exposure and build a sense of safety.

Therapeutic Approaches

Traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) remains widely used, focusing on maladaptive thought and behavior patterns and providing alternative coping strategies.

Emerging therapies target maladaptive subconscious brain processes. With these therapies, the brain is treated as the generator of pain. These therapies combine pain science education with exposure-based therapies that facilitate changing the response of the brain away from fear and toward messages of safety:

- Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT): In a randomized controlled trial of chronic back pain, 66% of participants receiving PRT reported being pain-free or nearly pain-free at 4 weeks, compared with 20% receiving a placebo and 10% receiving usual care.13 Benefits persisted at 1 year13 and 5 years,14 with functional MRI evidence of restored gray matter volume in the anterior cingulate cortex at 1 year.13 Notably, participants shifted their attributions of pain causation toward brain/psychological factors, from negligible at baseline to 40% after treatment.15

- Emotional Awareness and Expression Therapy: An emotion-focused, psychodynamic-informed therapy, it addresses unresolved trauma, stress, and interpersonal conflict, aiming to reduce fear-driven somatic symptoms.16 A recent study of elderly veterans showed a significant reduction in the brief pain inventory at 10 weeks and 6 months when compared to CBT.17

- Psychophysiologic Symptom Relief Therapy: A four-component program (pain education, graded physical activity, emotional expression, and stress reduction) shown to reduce disability more effectively than usual care or mindfulness-based stress reduction in nonspecific chronic back pain.18

Importantly, brain-based approaches are not entirely new to pain medicine. In complex regional pain syndrome, clinicians have long used Graded Motor Imagery, a stepwise rehabilitation strategy involving laterality recognition, motor imagery, and mirror therapy that targets cortical reorganization and maladaptive neuroplasticity, demonstrating that brain-directed treatments are already embedded in clinical practice.

Diagnosis of Neuroplastic Pain

A thorough history and physical examination remain central. Secondary pain must first be excluded, and imaging should be used judiciously and carefully explained to avoid confounding incidental findings (eg, “normal abnormalities” such as degenerative disc disease19).

Key diagnostic queries include:

- Onset and duration: Does the course correspond to the expected course of tissue healing?

- Distribution: Does pain location fit structural pathology?

- Provocation: Do aggravating factors reflect plausible tissue stress?

Some positive diagnostic clues for neuroplastic pain include:

- Pain persists, worsens, or recurs after tissue healing.

- Pain involves one side of the body, face, or torso.

- Pain is spreading to multiple regions.

- Pain is triggered by attention or discussion of pain.

- Pain is exacerbated by emotional stress.

Management Principles

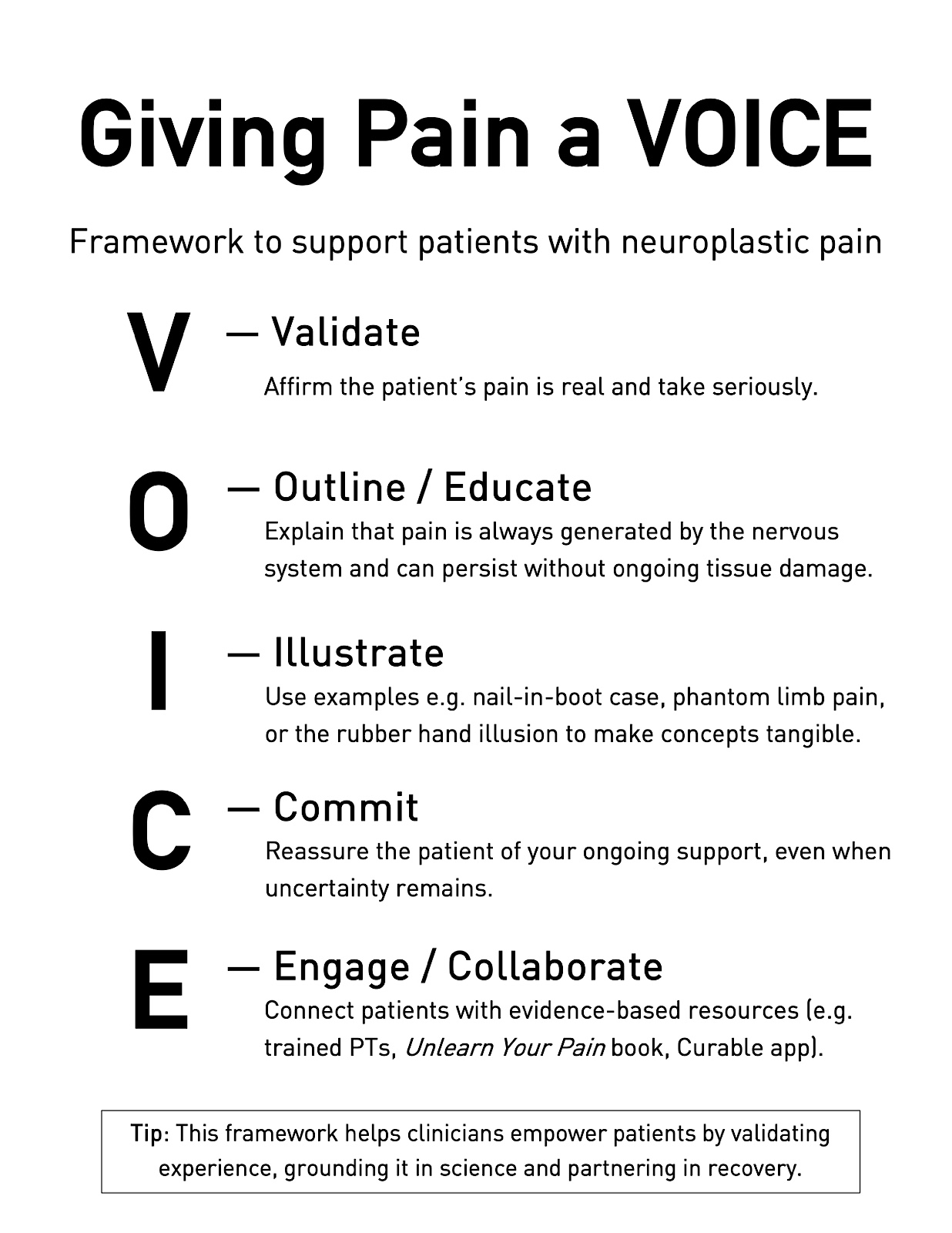

Once a diagnosis of neuroplastic pain is made, the clinician should:

- Validate the patients’ experience and affirm that their pain is real.

- Outline/Educate that pain is always generated by the nervous system.

- Illustrate with examples such as the nail-in-boot case, phantom limb pain, or the rubber hand illusion.

- Commit to supporting the patient, even in the face of uncertainty.

- Engage with evidence-based resources (eg, pain science-trained physical therapists, Unlearn Your Pain, Curable app, etc.).

Conclusion

Neuroplastic pain reflects maladaptive reorganization of neural circuits, in which fear, anxiety, and emotion circuits sustain pain independent of tissue injury. Evidence from neuroimaging and clinical trials supports brain-based mechanisms and demonstrates the effectiveness of emerging psychotherapeutic interventions. Effective management hinges on recognition, patient education, and engagement with pain science–based resources.

Permission

Figure 1: Reproduced from Thériault (2022) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

References

- Fisher JP, Hassan DT, O’Connor N. Minerva. BMJ 1995;310(6971):70. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6971.70

- IASP News. Washington, DC: International Association for the Study of Pain. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain. Published July 16, 2020. Accessed October 9, 2025.

- Wall PD, McMahon SB. The relationship of perceived pain to afferent nerve impulses. Trends Neurosci 1986;9(6):254-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(86)90070-6

- Melzack R, Rose G, McGinty D. Skin sensitivity to thermal stimuli. Exp Neurol 1962;6(3):300–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4886(62)90045-6

- Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain Pain Supercharged. Adelaide, Australia: NOI Group Publications; 2017.

- Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, et al. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2098-2110. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00392-5

- Botvinick M, Cohen J. Rubber hands “feel” touch that eyes see. Nature 1998;391(6669):756.https://doi.org/10.1038/35784

- Thériault R, Landry M, Raz A. The rubber hand illusion: top-down attention modulates embodiment. Q J Exp Psychol2022;75(6):1125-38. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470218221078858

- Rubber Arm Experiment. YouTube. https://youtu.be/xdxlT68ygt8. Published March 15, 2025. Accessed October 9, 2025.

- Derbyshire SWG, Whalley MG, Stenger VA, Oakley DA. Cerebral activation during hypnotically induced and imagined pain. Neuroimage 2004;23(1):392-401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.04.033

- Hashmi JA, Baliki MN, Huang L, et al. Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits. Brain 2013;136(9):2751-68. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt211

- Lumley MA, Stanton AL, et al. Pain and emotion: a biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol2011;67(9):942-68. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20816

- Ashar YK, Gordon A, Schubiner H, et al. Effect of pain reprocessing therapy vs placebo and usual care for patients with chronic back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79(1):13-23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2669

- Ashar YK, Gordon A, Schubiner H, et al. Pain reprocessing therapy vs placebo and usual care for patients with chronic back pain: 5-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2025;82(10):1049-51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.1844

- Ashar YK, Gordon A, Schubiner H, et al. Reattribution to mind-brain processes and recovery from chronic back pain: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6(9):e2333846. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.33846

- Maroti D, Frisch S, Lumley MA. To feel is to heal: introduction to emotional awareness and expression therapy. Schmerz 2025;39(4):256-62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-025-00878-6

- Yarns BC, Lumley MA, Cassidy J, et al. Emotional awareness and expression therapy vs cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain in older veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7(6):e2415842. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15842

- Donnino MW et al. Psychophysiologic symptom relief therapy for chronic back pain: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Pain Rep 2021;6(3):e959. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000959

- Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, et al. Systematic literature review of imaging features of spinal degeneration in asymptomatic populations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36(4):811-16. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4173