POCUS Spotlight: Point-of-Care Ultrasound for the Obstetric Anesthesiologist

Cite as: Sheikh M, Cubillos J, Arzola C, et al. POCUS spotlight: point-of-care ultrasound for the obstetric anesthesiologist . ASRA Pain Medicine News 2026;51. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020126.011.

POCUS Spotlight

Introduction

Obstetric anesthesiologists increasingly use point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to provide rapid diagnosis at the point of care and, if indicated, timely treatment. POCUS can be both diagnostic (assessment of the optic nerve sheath, heart, lungs, gastric contents, and abdomen) and procedural (front-of-neck airway, regional blocks, neuraxial anesthesia, and vascular access). Pregnant patients are becoming increasingly complex due to comorbidities, such as congenital heart disease, hypertensive disorders, obesity, advanced maternal age, and placenta accreta spectrum. Complications secondary to cardiovascular conditions, postpartum hemorrhage, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are among the top preventable causes of maternal mortality. POCUS may be used to identify life-threatening conditions, such as hemorrhage, peripartum cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, and pneumothorax. In addition, it may be used to facilitate regional blocks, neuraxial analgesia, vascular access, and front-of-neck-airway access. POCUS can also guide decision-making when the NPO status is unclear. There are unique considerations for pregnant patients due to their altered anatomy and physiology. This review highlights POCUS applications that may be useful to obstetric anesthesiologists.

Optic Nerve

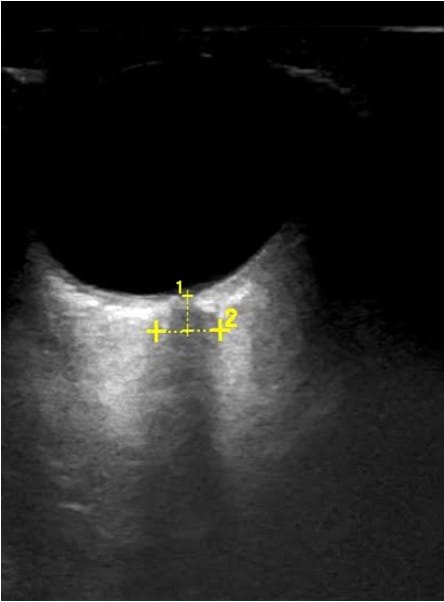

Optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) >5.8 mm has been shown to be associated with elevated intracranial pressure (>20 mmHg).1 To measure ONSD, the patient is placed in a semi-recumbent position, and a high-frequency linear probe is applied gently on the upper eyelid without excessive pressure (Figure 1).2 Measurements are taken 3mm behind the globe in both transverse and sagittal views (Figure 2). ONSD is calculated by taking the mean of the four values (two per eye). Though studies have indicated that ONSD may be increased in pregnant patients who have a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features, the clinical relevance of these findings is still under debate.3

Airway

In pregnancy, physiologic changes to the airway, including mucosal capillary engorgement, increase the incidence of difficult intubation (1 in 49) and failed intubation (1 in 808).4 With the advent of video laryngoscopy and improved laryngeal mask airways, hypoxemic arrest from failed intubation and ventilation is extremely rare. In the cannot intubate, cannot ventilate scenario, an emergent front-of-neck airway (FONA) is the final step in difficult airway algorithms.5

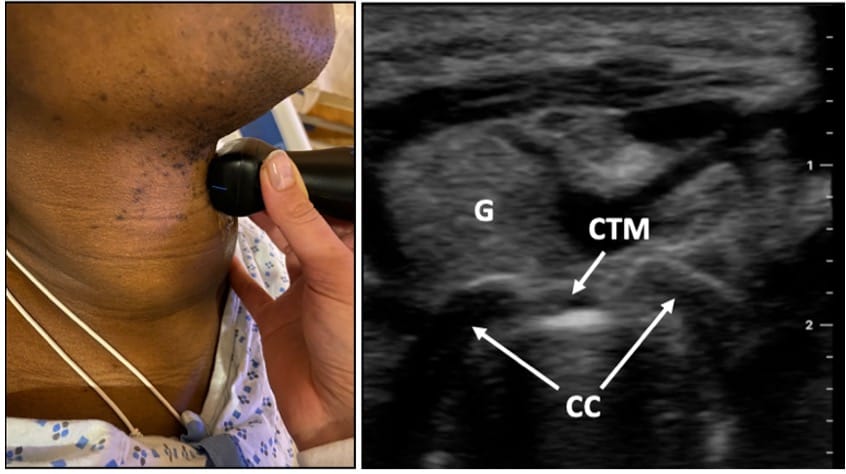

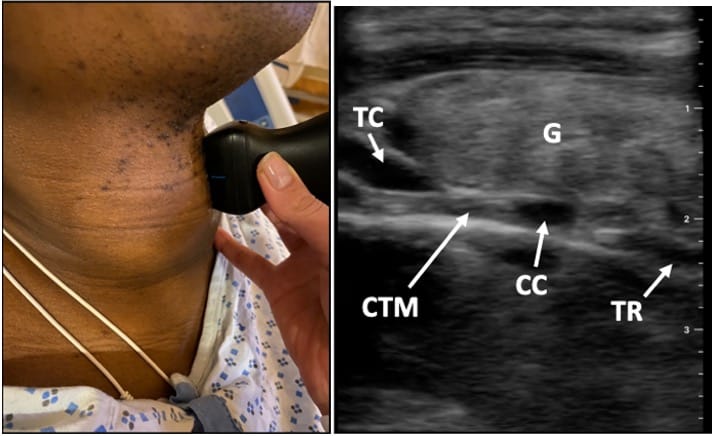

Ultrasound can reliably identify airway anatomy before possible emergent cricothyrotomy.6 The patient is placed in the supine position, and a linear, high-frequency probe is used to obtain images in the transverse and mid-sagittal planes (Figure 3).7 The hyperechoic cricothyroid membrane is located between hypoechoic thyroid and cricoid cartilages. In the mid-sagittal view, the thyroid and cricoid cartilages appear as dark, hypoechoic structures, with the cricothyroid membrane located between them (Figure 4). When scanning caudally in the mid-sagittal plane, tracheal rings appear as small, hypoechoic structures described as a “string of pearls” (Video 1). Thyroid masses, such as goiters or malignancies, can make intubation extremely difficult. Airway assessment with ultrasound may be useful to identify relevant anatomy in case emergent FONA becomes necessary.

CTM = cricothyroid membrane, CC = cricoid cartilage, G = goiter

TC = thyroid cartilage, CTM = cricothyroid membrane, CC = cricoid cartilage, TR = tracheal rings, G = goiter

POCUS may be used to identify life-threatening conditions, such as hemorrhage, peripartum cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, and pneumothorax.

Focused Cardiac Ultrasound (FCU)

Cardiovascular disorders are the leading cause of maternal mortality in developed countries.8.9 Improved survival rates in children born with congenital heart disease and increasing risk factors have created a steadily rising obstetric population with cardiac disease.10 Previous concerns about the availability of the correct ultrasound probe (phased array) are moot, as the obstetric curvilinear probe can also be used to perform FCU in >91% of patients.11,12

Pregnancy is an optimal state for performing FCU, owing to cephalad, anterior, and lateral displacement of the heart by the gravid uterus and frequent use of the left “tilt” position to relieve compression of the inferior vena cava, which is ideal for several echocardiographic views.13,14 FCU is also feasible under less ideal conditions, such as when performed by novices in the operating room with a patient under neuraxial blockade, in the supine position, and with sterile drapes that limit full access.15 FCU is noninvasive compared with transesophageal echocardiography and pulmonary artery catheterization, while allowing real-time assessment of cardiac chamber dimensions, biventricular systolic function, pericardial effusion, gross valvular dysfunction, and volume status.

During FCU, five standard views are used to rapidly assess cardiac function.16

Subcostal Four-Chamber and Inferior Vena Cava (IVC)

The subcostal four-chamber view can assess pericardial effusion, intracardiac masses, systolic function, and cardiac chamber dimensions (eg, right heart strain). By rotating the probe 90 degrees counterclockwise, we can visualize the IVC through the liver, measure its diameter, and assess variability with respiration to estimate central venous pressure (Video 2). The subcostal view requires considerable pressure underneath the xiphoid process, which can be uncomfortable in full-term pregnant patients.

Apical Four-Chamber

In apical four-chamber view (A4CH), we assess for biventricular function, left and right ventricular size, pericardial effusion, and valvular abnormalities (Video 3). The A4CH is ideal when a patient is in the left lateral position with the left arm up to open the rib spaces. The probe is placed at the point of maximal impulse, or as traditionally taught, at the sixth intercostal space; the view is obtained at higher intercostal spaces in advanced gestational ages. Left ventricular ejection fraction can be visually estimated or quantified using simple metrics, such as fractional shortening, fractional area change, or mitral annular plane systolic excursion. Right ventricular function can be assessed by fractional area change +/- tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion. Because FCU is primarily performed in the acute setting, where an obstetric anesthesiologist may have limited time, it is a targeted diagnostic exam aimed at ruling out obvious severe pathology, with limited need for quantitative assessments or calculations.

Parasternal Long Axis

Parasternal long axis (PLAX) is the preferred view in pregnancy as increased intra-abdominal pressure pushes the heart upwards into the chest. The probe marker points to the patient’s right shoulder. We begin scanning at the third intercostal space at the left sternal border and move one intercostal space up or down to optimize the view. In PLAX, we can assess cardiac dimensions, systolic function, aortic root dilation, and mitral and aortic valvular abnormalities (Video 4). The descending aorta is an important landmark. If hypoechoic, dark fluid is seen anterior to the aorta, it is a pericardial effusion. If it is posterior to the aorta, it is a pleural effusion. LVFS can be calculated using M-mode and measuring the change in left ventricular (LV) diameter between systole and diastole.

Parasternal Short Axis

To obtain the parasternal short-axis (PSAX) view, one should optimize the PLAX view and center the LV on the screen, then rotate 90 degrees from the PLAX position, pointing the indicator toward the patient’s left shoulder. In PSAX, we can estimate the patient’s volume status, systolic function, contractility, LV and right ventricular dimensions (Video 5).

The basic views can be combined with fetal heart rate assessment as part of the rapid obstetric screening echocardiography scan.13

Lung

The physiologic changes of pregnancy can increase the risk of pulmonary edema, especially in the third trimester and postpartum, due to increased blood volume and autotransfusion, with approximately 500 ml of blood returning to the heart during uterine involution.

Specific considerations for lung ultrasound include cephalad displacement of the diaphragm and possible difficult image acquisition in the left hemithorax due to upward displacement of the heart. Because of gravity, pneumothorax is best identified in non-dependent lung regions, whereas interstitial pulmonary edema and pleural effusions are best identified in dependent, basal lung regions. A high-frequency linear probe should be used to assess lung sliding when a pneumothorax is suspected. The low-frequency, or curvilinear, probes should be chosen for interstitial edema, pleural effusion, and evaluation of lung tissue.17 Pleural scanning is a part of FCU and is useful to identify effusions (Video 6). Pleural effusion will appear as a hypoechoic, dark fluid.

Bright, hyperechoic, laser-like projections are called B-lines. One or two per window can be normal in dependent regions. More than 3 in multiple lung windows is abnormal and a sign of fluid accumulation in the lung (Video 7).

In one study, 2.7% of healthy, term parturients undergoing unplanned intrapartum cesarean delivery were found to have pulmonary interstitial syndrome (PIS).18 Furthermore, PIS was found to be present in 24% of patients with late-onset preeclampsia with severe features.3 Lung ultrasound is an important application to guide fluid management in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, parturients with sepsis, and postpartum hemorrhage.

Focused Assessment With Sonography In Trauma (FAST)

The focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was initially conceived more than 25 years ago as a bedside sonographic evaluation protocol to detect free fluid in the abdominal cavity in trauma patients in an efficient and standardized manner, thereby limiting the need for peritoneal lavage (Videos 8 & 9). Over time, its use has gradually expanded beyond trauma in emergency services to include critical care and postoperative settings, such as the immediate postsurgical period in the recovery room.

More recently, the FAST exam has been gradually incorporated into the perioperative care of obstetric patients under the acronym Focused Assessment with Sonography in Obstetrics (FASO).19 It has been proposed that FASO should include, in addition to the FAST exam classically described areas, a systematic assessment of the uterine cavity with the option of measuring the IVC as an indirect indicator of volume status.20 Rincón and colleagues published an interesting clinical case demonstrating its utility in the obstetric perioperative context, especially when the reason for hemodynamic instability is unclear.19 Early detection of free fluid in these cases allows for a faster response and intervention, such as surgical reintervention, activation of massive transfusion protocols, or ordering additional diagnostic imaging. For FASO to be optimally utilized, it must be integrated into a structured framework, such as the proposed I-AIM approach (Indication, Acquisition, Interpretation, and Medical Decision-making), which helps ensure that ultrasound findings translate directly into timely clinical decisions.21

Although the FAST exam was established for the management of polytrauma patients, its adaptation to the care of pregnant patients is expanding and growing with emerging applications in obstetric anesthesia practice.21 In addition to detecting hemoperitoneum, peripartum ultrasound has the potential to differentiate causes of hemorrhage, such as retained placenta, abnormally adherent placenta, uterine rupture, and uterine inversion.22,23 Expertise in these types of studies is clearly within the domain of obstetricians at present, but that does not mean they should not be considered as part of the FASO exam. In studies of low-risk populations, reference values for postpartum uterine dimensions have been established, and the occasional presence of small amounts of physiologic free fluid in the pelvis has been described; these findings are key to avoiding overdiagnosis and unnecessary procedures.20 For this reason, it is suggested that both ultrasound evaluation and subsequent clinical decision-making be carried out jointly with a multidisciplinary approach of the peripartum care team, where different levels of expertise are complementary and educational, supporting the development of a precise, rapid, and repeatable diagnostic technique for decision-making in early recognition, timely intervention, and management of postpartum hemorrhage to improve maternal outcomes.

Gastric

Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents represents a significant and potentially catastrophic complication in the perioperative setting, and it remains a leading cause of perioperative morbidity and mortality. While the incidence in general anesthesia is 1:4,000 in all elective surgeries, it increases significantly in the obstetric population to 1:700 general anesthetics due to physiological changes (decreased gastric pH, increased abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus, and progesterone-mediated relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter).24 Gastric POCUS addresses this critical concern by providing a rapid, noninvasive, bedside method for assessing the volume and nature of gastric contents.25-28 This tool is vital in obstetrics, where expedited procedures and complex physiology demand objective, real-time risk assessment, enhancing patient safety and mitigating severe complications associated with high morbidity and mortality.24

Traditional NPO guidelines, while foundational,26 fail to accurately reflect gastric status in complex patient populations because of physiological conditions that delay gastric emptying.29 Although most studies show favorable conditions before elective cesarean delivery, some studies do not always guarantee an empty stomach.29 Gastric emptying for solids is delayed during labor; women in labor who have eaten solids in the last 8 hours are highly likely to still harbor high-risk contents.29 POCUS overcomes these limitations by offering objective, visual evidence of gastric status, which generalized time-based fasting cannot reliably ascertain.27

The technique targets the gastric antrum in an epigastric parasagittal plane.27 Assessment uses the qualitative Perlas grading (Grade 0: empty, Grade 1 and 2: evidence of clear fluids; Grade 3: solids/thick fluid), followed by quantitative measurement of the antral cross-sectional area (CSA) if clear fluid is present (Videos 10, 11, & 12).29,30 High aspiration risk is defined by gastric volume > 1.5 mL/kg.27 Unlike non-pregnant adults, the protocol for pregnant women in the second and third trimesters necessitates scanning in the right lateral semi-recumbent and semi-recumbent positions.32 This change in positioning is crucial to avoid the detrimental effect of supine aortocaval compression from the gravid uterus, which otherwise can obscure the gastric antrum. A high-risk finding corresponds to an antral CSA cutoff of >9.6 cm2 (10 cm2) in this position.33,34

POCUS is indicated when a patient's fasting status is uncertain or in physiological states known to delay gastric emptying.30 Gastric emptying is observed to be decreased in the first trimester and in labor; the use of systemic opioids further delays it. Conversely, epidural analgesia increases gastric emptying, although it does not return to baseline.25 This tool is essential for stratifying aspiration risk in labor and before urgent procedures, especially since standard fasting is unreliable in this complex patient population.29

Objective data from POCUS directly influence surgical timing and the choice of anesthetic technique.30 It allows providers to move beyond the universal assumption of a "full stomach," which is especially important in obstetrics. A low-risk assessment may permit a safer or less invasive airway approach, while a high-risk finding necessitates full aspiration precautions, such as rapid sequence induction if general anesthesia is planned.30 The objective data ensures that the safest anesthetic choices are made, enhancing patient safety and optimizing perioperative efficiency.

Research demonstrates good inter-rater reliability for qualitative assessment in the obstetric population, but it is inherently operator-dependent, necessitating specialized training.30 Technical challenges specific to pregnancy include increased scanning depth and displacement of the stomach by the gravid uterus.31,32 Furthermore, findings can be unreliable in patients with abnormal underlying gastric anatomy, such as those who have undergone previous gastric resection or have a large hiatal hernia.27 Despite these limitations, the tool’s ability to reliably visualize stomach contents and estimate volume makes it a powerful safety advancement.27

Gastric POCUS fundamentally reshapes obstetric risk assessment by providing objective, real-time data to address the physiological complexities and unpredictable nature of gastric emptying in pregnant patients. This individualized risk stratification is crucial for determining the safest anesthetic and airway management techniques, ultimately enhancing patient safety and improving perioperative outcomes in a demanding obstetric setting.

Neuraxial

Anesthesiologists accurately identify the correct vertebral interspace in only 29% of cases.35 Carvalho and colleagues marked the intercristal line and subsequently identified the interspace with ultrasound, finding that the palpated line was above L4-5 in all patients and up to three interspaces higher. This increases the risk for spinal cord trauma as the conus medullaris of the spinal cord terminates below L1 in several patients. Studies have demonstrated that preprocedural neuraxial ultrasound can reduce the number of needle passes and attempts for epidurals and spinals. A systematic review of 31 RCTs and 1 meta-analysis found that neuraxial ultrasound can identify a given lumbar intervertebral space more accurately than landmark palpation alone.36 There is excellent correlation between ultrasound-measured depth and needle insertion depth to the epidural or intrathecal space, with a mean difference of 3 mm. There is also a reduction in the risk of traumatic procedures.

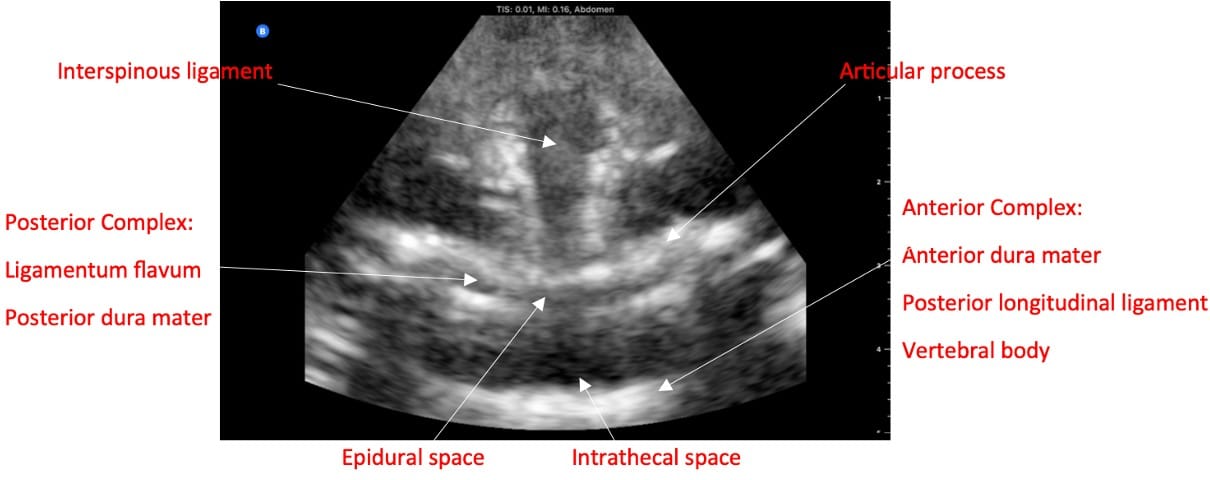

If the clinician does not have access to a dedicated ultrasound, they can use the obstetric ultrasound, which has the curvilinear probe.37 In the paramedian sagittal view, the sacrum appears as a flat, hyperechoic structure. The lamina and interspaces are visualized by scanning in a cephalad direction (Video 13). In transverse view, note that when the probe is on a spinous process, a dark acoustic shadow is present.38 Once scanning within an interspace and with possible tilting of the probe, one can visualize the ligaments, articular processes, and sometimes transverse processes (Figure 5). Ligamentum flavum and posterior dura mater often appear as a single hyperechoic line called the posterior complex. The dark band anterior to the posterior complex is the intrathecal space, as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) will appear dark. In front of the CSF is the anterior dura, the posterior longitudinal ligament, and the vertebral body, collectively called the anterior complex. In obese parturients, pressure is required to visualize the ligaments, so the depth to the epidural space may be underestimated.

Conclusion

It is essential for obstetric anesthesiologists to learn both diagnostic and procedural POCUS applications to provide the highest level of care to an increasingly complex obstetric population. By mastering these techniques, obstetric anesthesiologists have the potential to significantly reduce maternal morbidity and mortality.

References

- Amini A, Kariman H, Arhami Dolatabadi A, et al. Use of the sonographic diameter of optic nerve sheath to estimate intra-cranial pressure. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:236-9. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.ajem.2012.06.025

- Mehra C, Chakraborty A, Dikshit A. POCUS spotlight: point-of-care ultrasound of the eyes. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2024;49. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra050124.012

- Ortner CM, Krishnamoorthy V, Neethling E, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound abnormalities in late-onset severe preeclampsia: prevalence and association with serum albumin and brain natriuretic peptide. Anesth Analg 2019;128(6):1208-16. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000003759

- Reale SC, Bauer ME, Klumpner TT, et al. Multicenter perioperative outcomes group collaborators. Frequency and risk factors for difficult intubation in women undergoing general anesthesia for cesarean delivery: a multicenter retrospective cohort analysis. Anesthesiology 2022;136(5):697-708. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004173

- Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM, Popat M, et al. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association; Difficult Airway Society. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 2015;70(11):1286-306. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae

- Kristensen MS, Teoh WH, Rudolph SS. Ultrasonographic identification of the cricothyroid membrane: best evidence, techniques, and clinical impact. Br J Anaesth 2016;117 Suppl 1:i39-i48. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew176

- Kolli S, Singh M. POCUS spotlight: airway ultrasound. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2021;46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.52211/asra080121.046

- Knight MNM, Tuffnell D, Shakespeare J, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2013-2015. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/maternal-report-2021/MBRRACE-UK_Maternal_Report_2021_-_FINAL_-_WEB_VERSION.pdf. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford. Published November 2021. Accessed Month Day, Year.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. CDC Maternal Mortality Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-data/index.html. Published December 18, 2025. Accessed Month Day, Year.

- Connolly HM. Pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2005;7:305-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-005-0053-z

- Squires L, Conti D, Martinez E,et al. Curvilinear versus phased array transducers for peripartum focused cardiac ultrasound: a non-inferiority comparative crossover study. Abstract at SOAP Annual meeting, May 2024, Denver, CO, USA.

- Algodi M, Wolfe DS, Taub CC. The utility of maternal point of care ultrasound on labor and delivery wards. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2022;9(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd9010029

- Dennis AT. Transthoracic echocardiography in obstetric anaesthesia and obstetric critical illness. Int J Obstet Anesth 2011;20(2):160-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.11.007

- Jain D, Grejs AM, Bhavsar R, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound is feasible in parturients: a prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2017;61:1105-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12956

- Ortner CM, Sheikh M, Athar MW, et al. Feasibility of focused cardiac ultrasound performed by trainees during cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2024;139(2):332-8. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000006747

- Sjaus A, Kalagara H. POCUS spotlight: focused cardiac ultrasonography. ASRA Pain Medicine News. 2021;46. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra080121.047

- Manson W, Hogg R. How I do it: lung ultrasound. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2022;47. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020122.005

- Macias P, Wilson JG, Austin NS, et al. Point-of-care lung ultrasound pattern in healthy parturients: prevalence of pulmonary interstitial syndrome following vaginal delivery, elective and unplanned intrapartum cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg 2021;133(3):739-46. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005464

- Rincón C, Cubillos J, Arzola C. Postpartum hemorrhage emergency management using focused assessment with sonography for obstetrics (FASO): a case report. POCUS J 2019;4(2):17-19.

- Oba T, Hasegawa J, Arakaki T, et al. Reference values of focused assessment with sonography for obstetrics (FASO) in low-risk population. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29(24):4024-8. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1130820

- Manson WC, Kirksey M, Boublik J, et al. Focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) for the regional anesthesiologist and pain specialist. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2019;44(5):540-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2018-100312

- Oba T, Hasegawa J, Sekizawa A. Postpartum ultrasound: postpartum assessment using ultrasonography. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29(24):4029-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1223034

- Mappa I, Patrizi L, Maruotti GM, et al. The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of postpartum hemorrhage. J Clin Ultrasound 2023;51(6):362-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.23343

- Howle R, Sultan P, Shah R, et al. Gastric point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. Int J Obstet Anesthesia 2020; 44:24-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2020.05.005

- Lawson J, Howle R, Popivanov P, et al. Gastric emptying in pregnancy and its clinical implications: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth 2025; 134:124-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.09.005

- Rüggeberg A, Meybohm P, Nickel EA. Preoperative fasting and the risk of pulmonary aspiration—a narrative review of historical concepts, physiological effects, and new perspectives. BJA Open2024;10:100282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjao.2024.100282

- El-Boghdadly K, Wojcikiewicz T, Perlas A. Perioperative point-of-care gastric ultrasound. BJA Educ 2019; 19:219-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.03.003

- Baettig SJ, Filipovic MG, Hebeisen M, et al. Pre-operative gastric ultrasound in patients at risk of pulmonary aspiration: a prospective observational cohort study. Anaesthesia 2023;78:1327-37. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.16117

- Haskins SC, Bronshteyn YS, Ledbetter L, et al. ASRA pain medicine narrative review and expert practice recommendations for gastric point-of-care ultrasound to assess aspiration risk in medically complex patients undergoing regional anesthesia and pain procedures. Reg Anesth Pain Med2025:rapm-2024-106346. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2024-106346

- Perlas A, Putte PV de, Houwe PV, et al.I-AIM framework for point-of-care gastric ultrasound. Br J Anaesth 2016; 116:7-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev113

- Arzola C, Cubillos J, Perlas A, et al. Interrater reliability of qualitative ultrasound assessment of gastric content in the third trimester of pregnancy. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113:1018-23. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu257

- Perlas A, Arzola C, Putte PV de. Point-of-care gastric ultrasound and aspiration risk assessment: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth 2018;65:437-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-1031-9

- Arzola C, Perlas A, Siddiqui NT, et al. Bedside gastric ultrasonography in term pregnant women before elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesia Analg 2015; 121:752-8. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000000818

- Perlas A, Arzola C, Portela N, et al. Gastric volume and antral area in the fasting state: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Anesthesiology 2024; 140:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004914

- Margarido CB, Mikhael R, Arzola C, et al. The intercristal line determined by palpation is not a reliable anatomical landmark for neuraxial anesthesia. Can J Anaesth 2011;58(3):262-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-022-03045-8

- Perlas A, Chaparro LE, Chin KJ. Lumbar neuraxial ultrasound for spinal and epidural anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016;41(2):251-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000184

- Kolli S, Narouze S, Kalagara H. How I do it: neuraxial ultrasound. ASRA Pain Medicine News2021;46. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110121.068

- Talati C, Carvalho, JCA. Spinal ultrasound for neuraxial anesthesia placement. Obstetric Anesthesiology 2019;24-29. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316155479.006