How I Do It: Caudal Block

Cite as: Ponde V, Rath A, Kulkarni R. How I do it: caudal block. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2026;51. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra020126.009.

How I Do It

Introduction

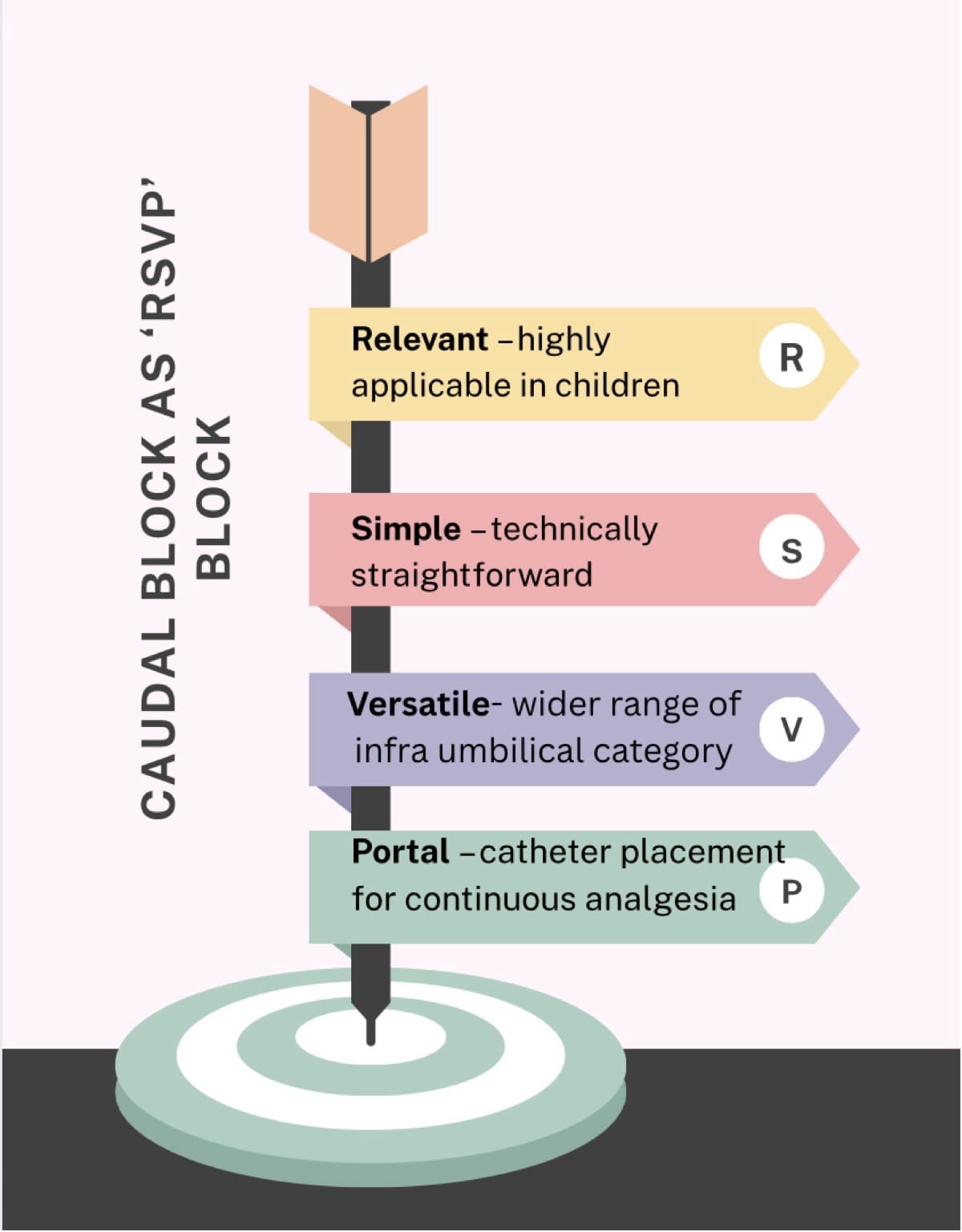

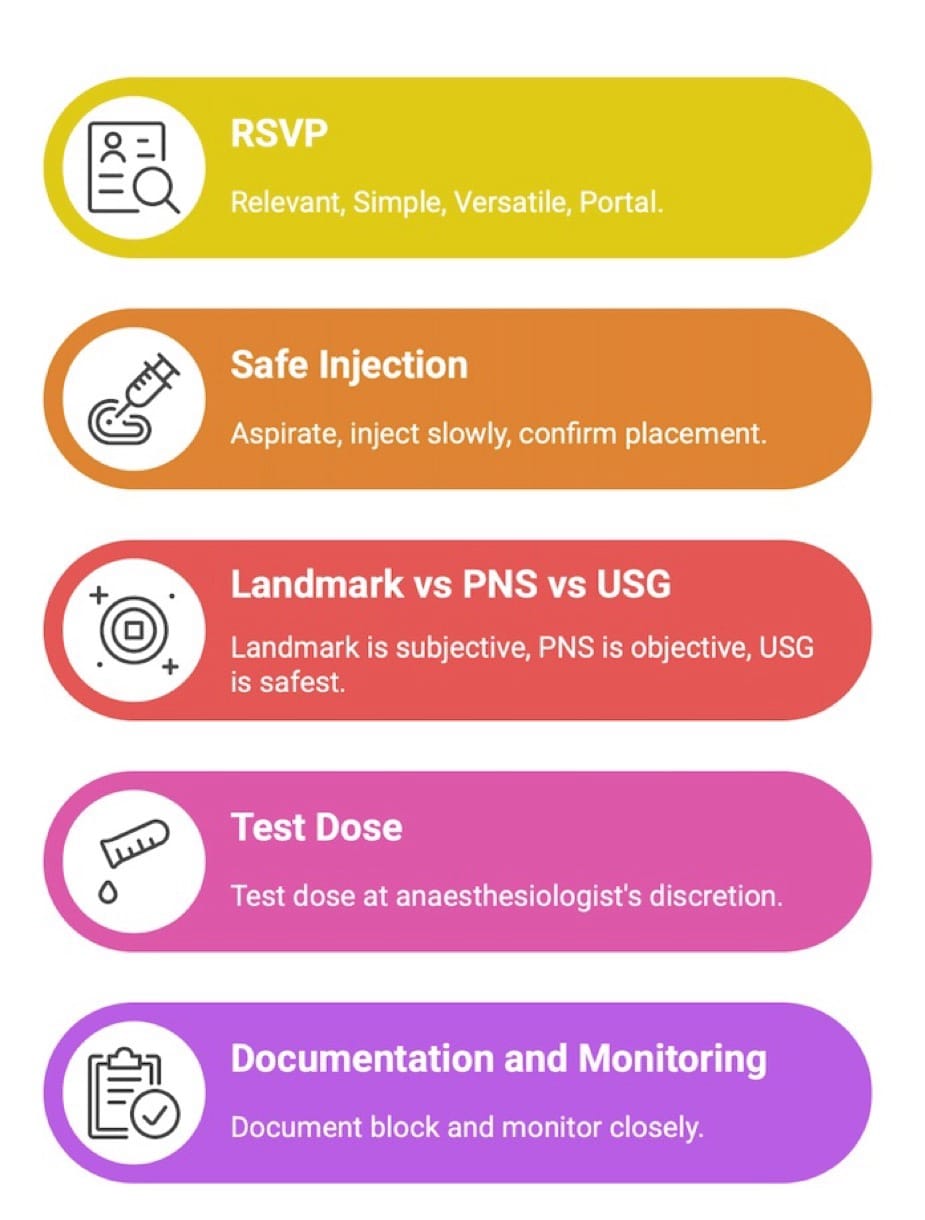

Caudal epidural block is one of the most widely practiced techniques in children and remains a cornerstone of pediatric regional anesthesia, providing reliable infra-umbilical analgesia with minimal systemic effects. In 1933, Meredith Campbell described caudal anesthesia for urologic surgical procedures in children.1 Understanding developmental anatomy and technique selection ensures optimal analgesia and minimizes complications, reaffirming caudal anesthesia as a time-tested, indispensable pediatric block. It can be remembered as a Relevant, Simple, Versatile, and Portal (RSVP block) (Figure 1)

This article focuses on the caudal epidural block in its various modalities:

- Anatomical nuances and age-related changes

- Generations of techniques

- Practical troubleshooting for each

- Drug dosages and adjuvants

- Safety pearls and complications

Anatomy of the Caudal Space

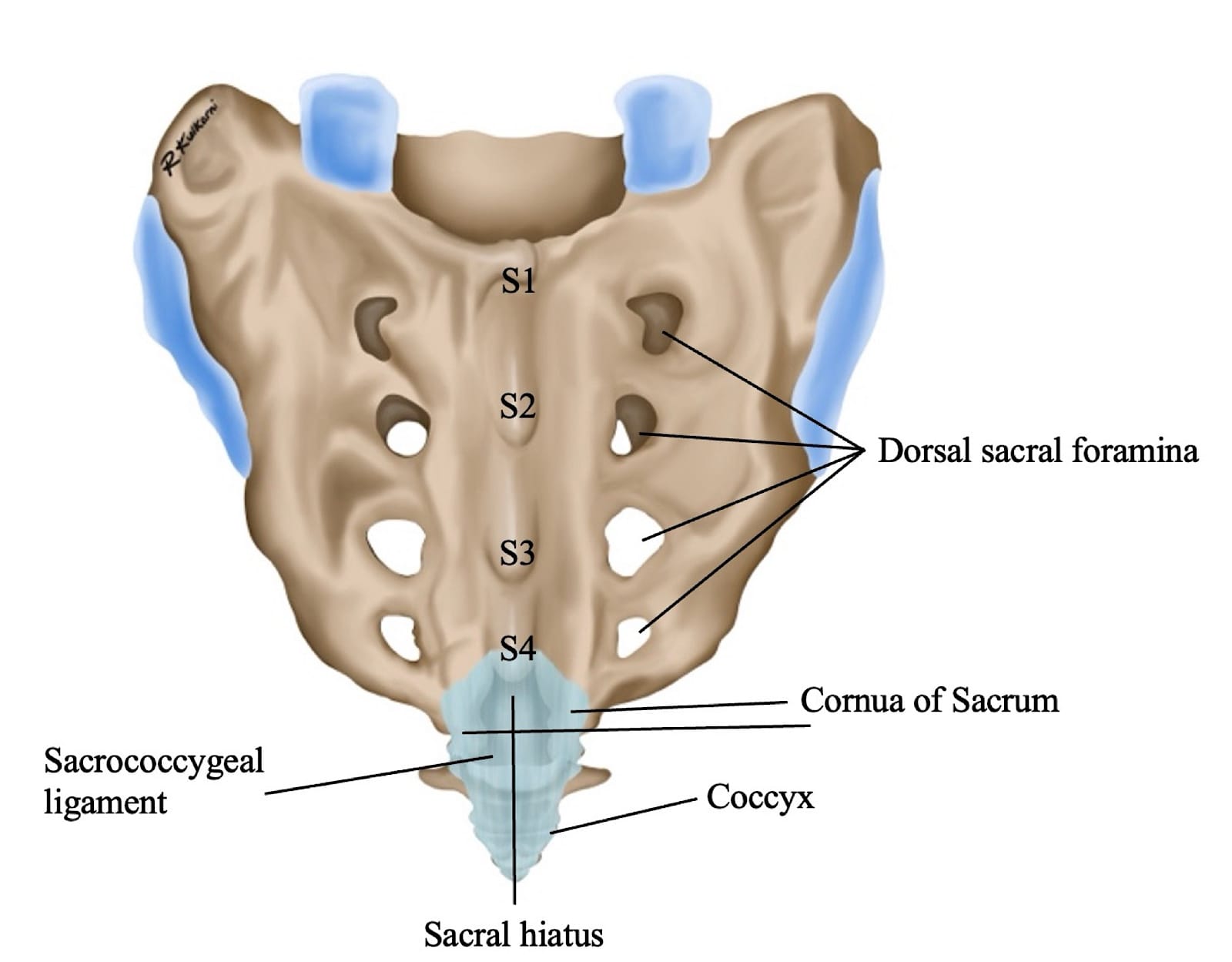

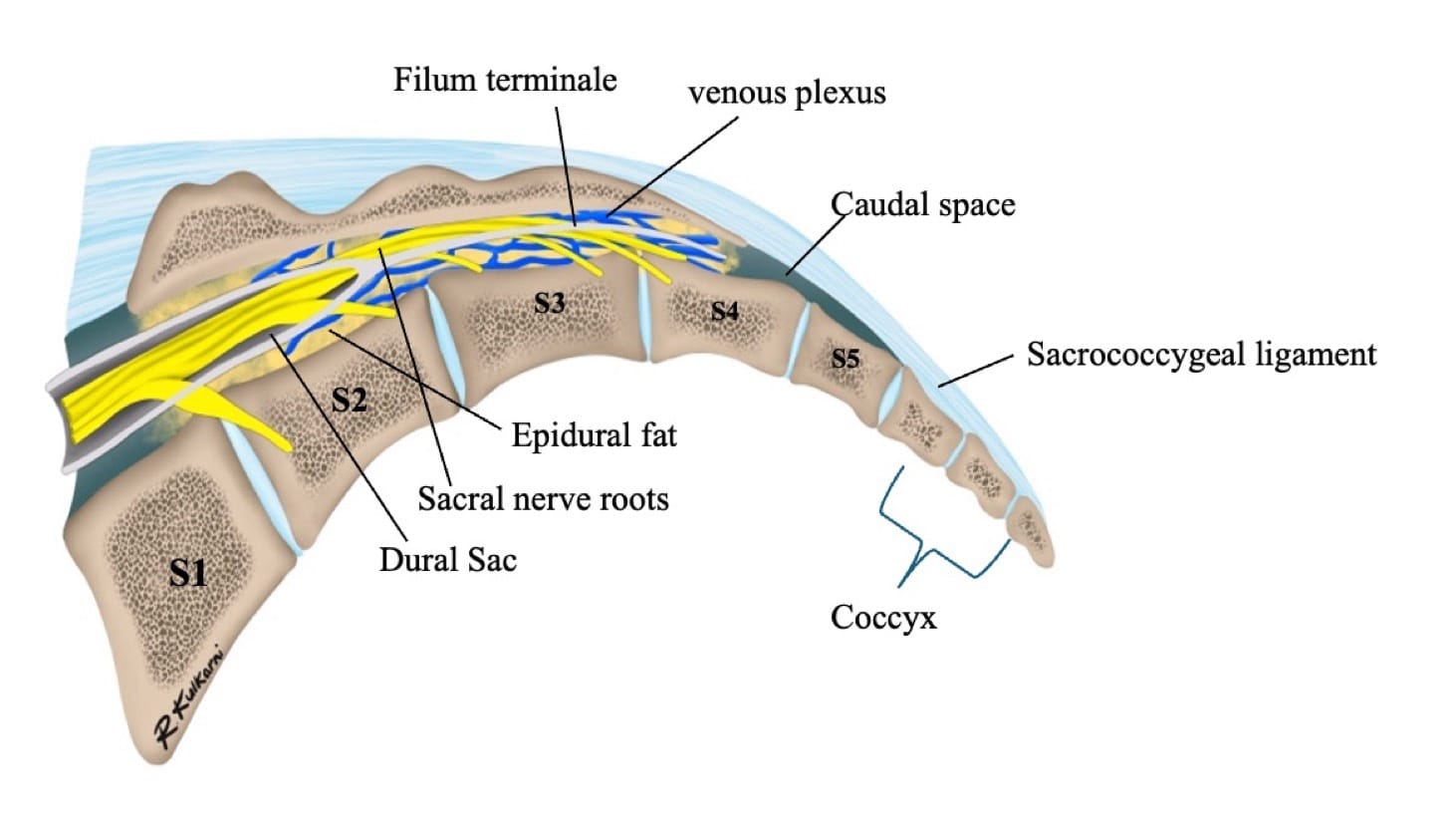

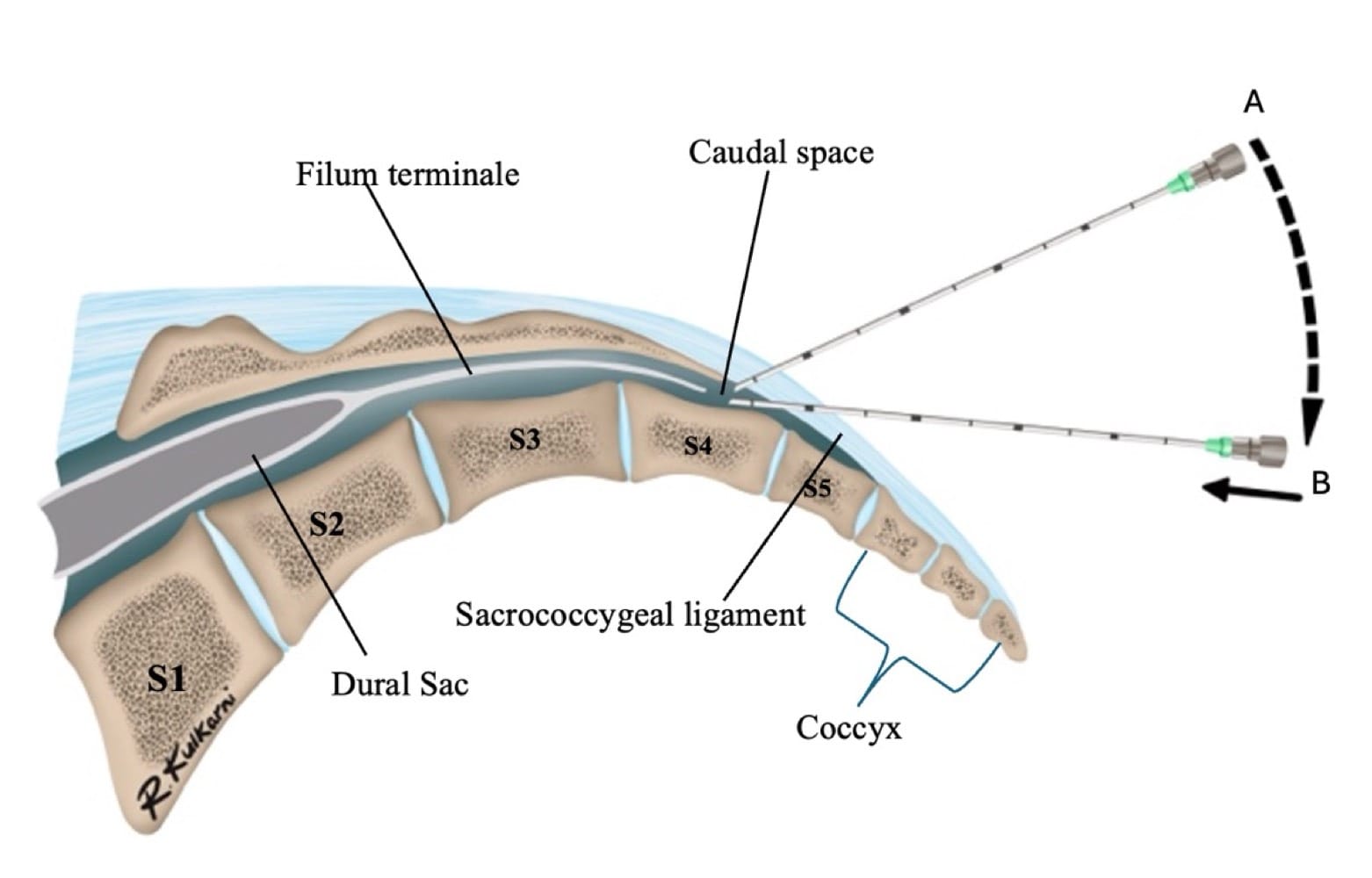

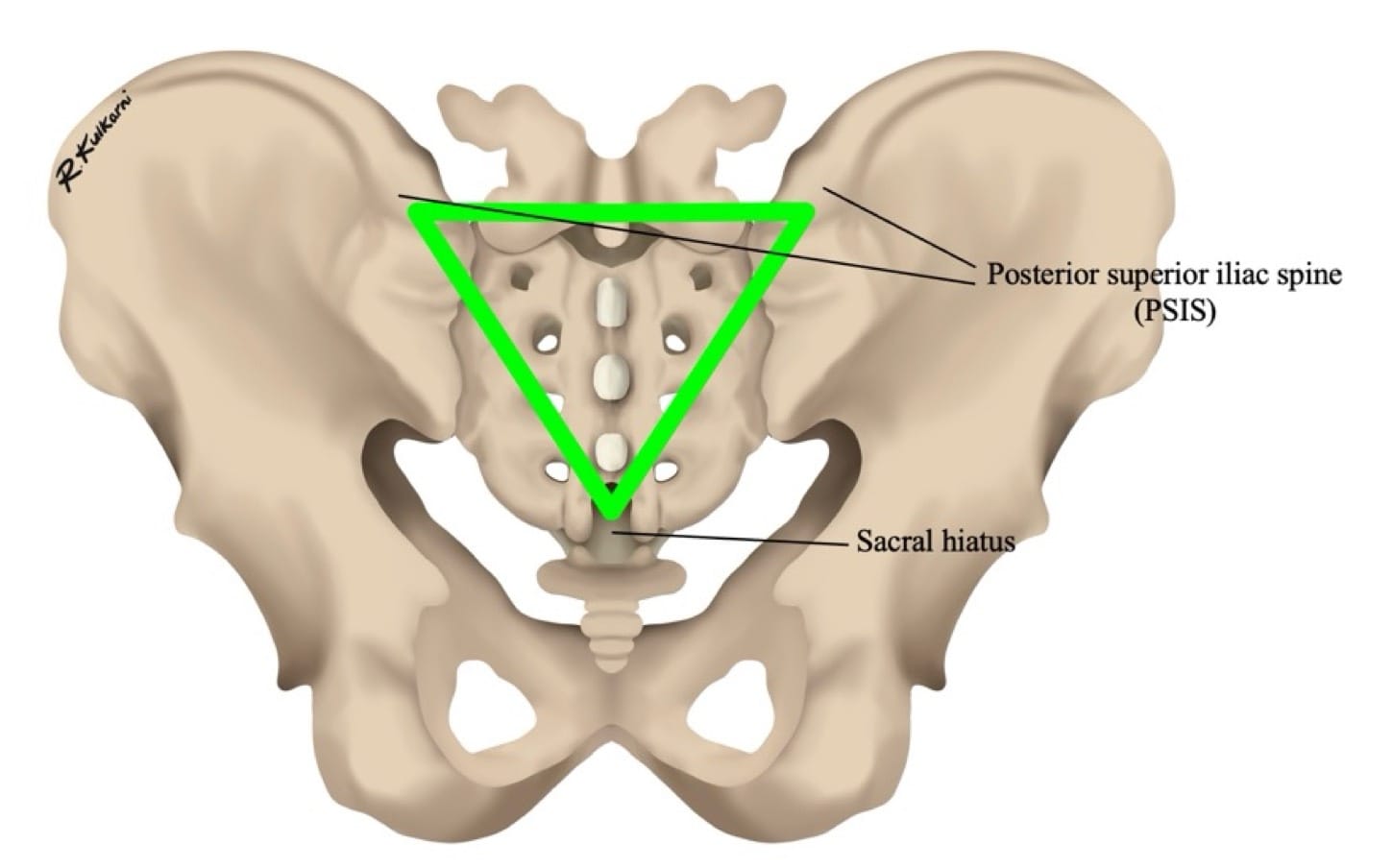

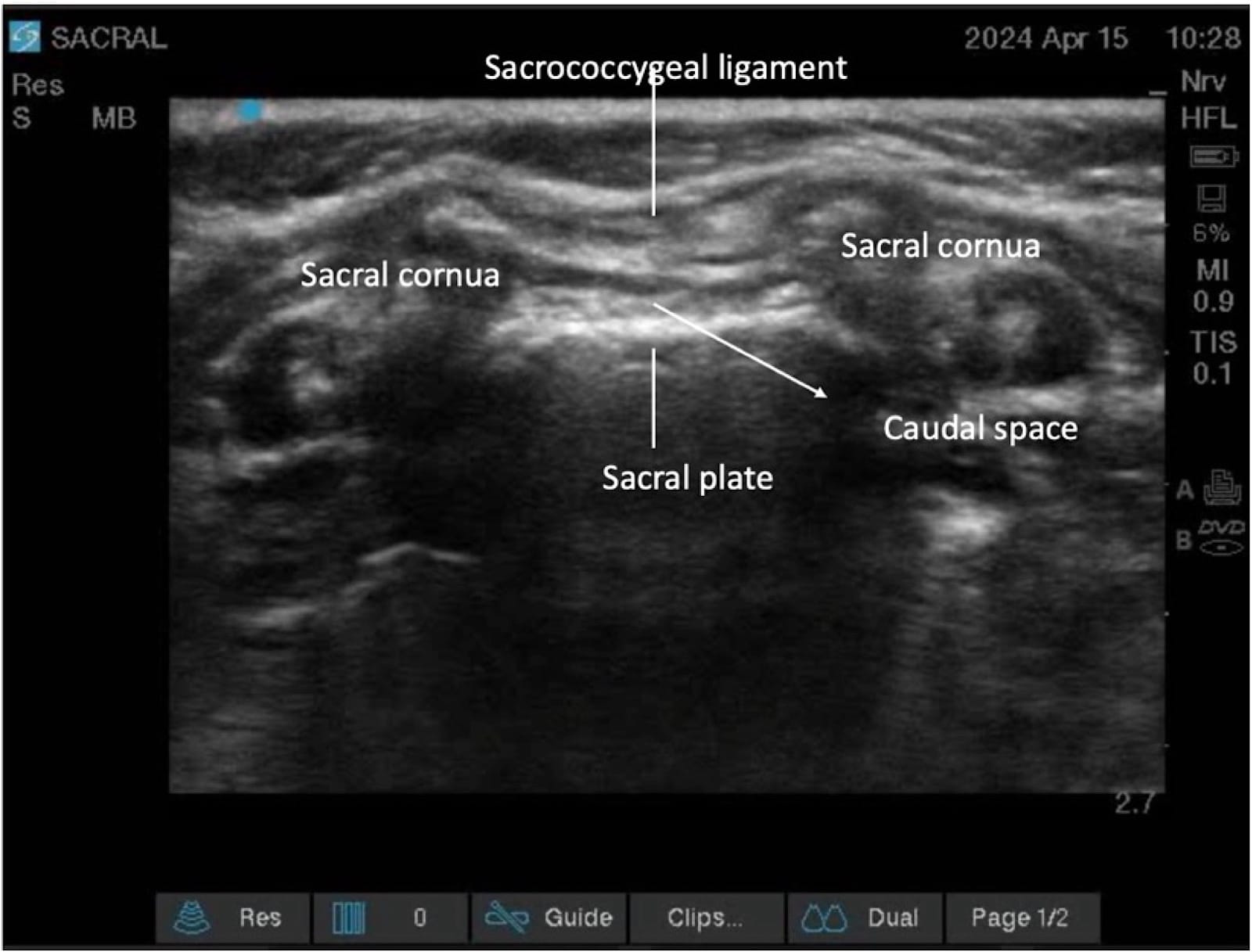

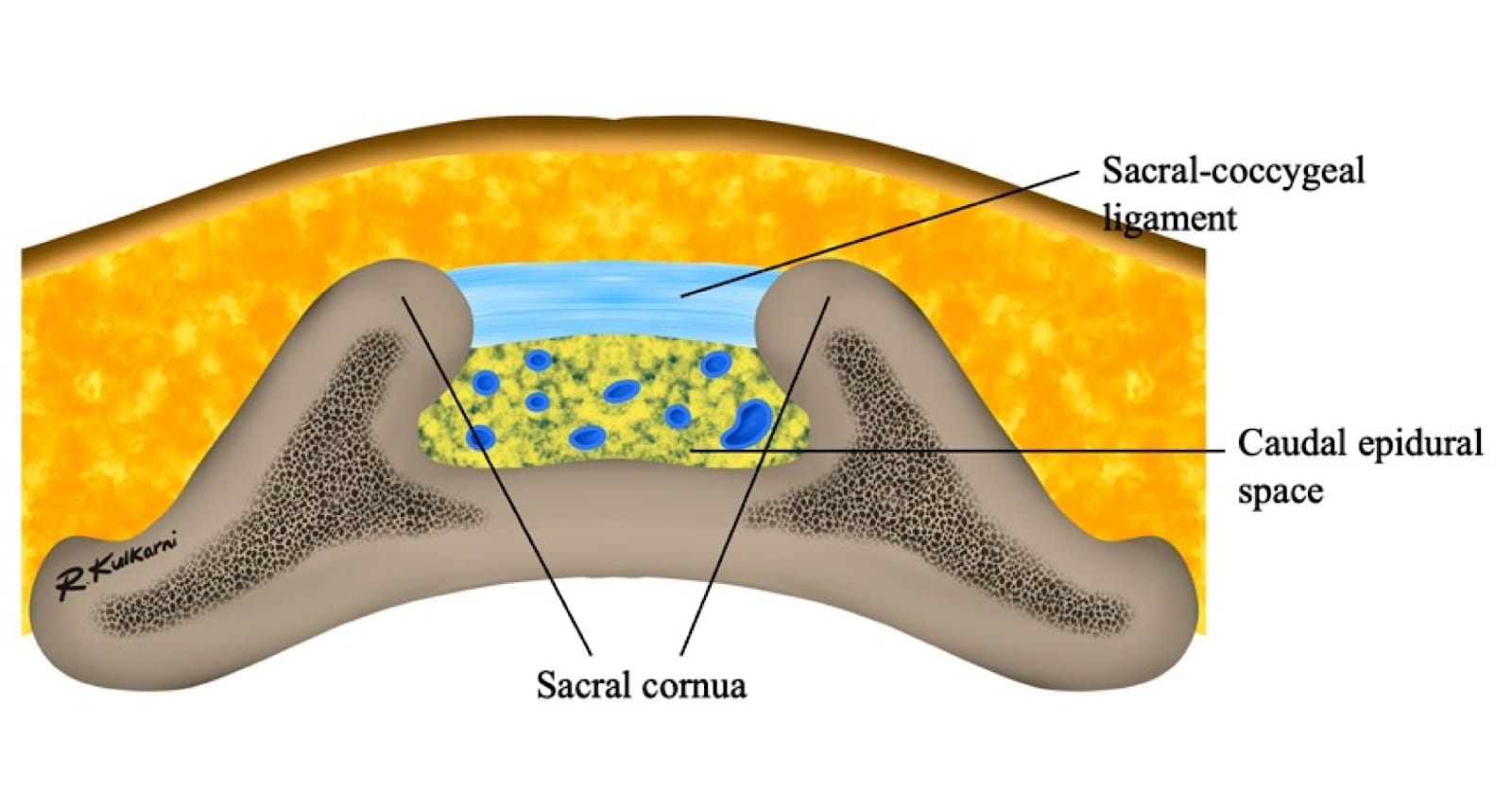

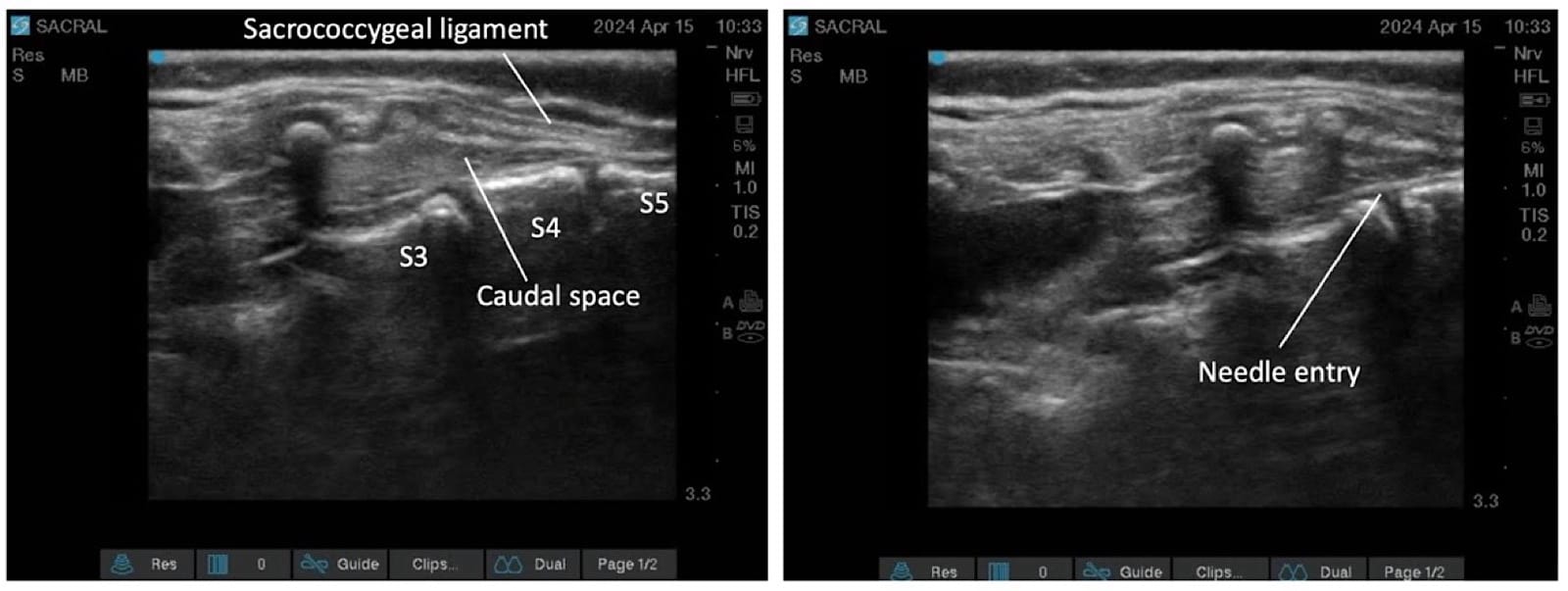

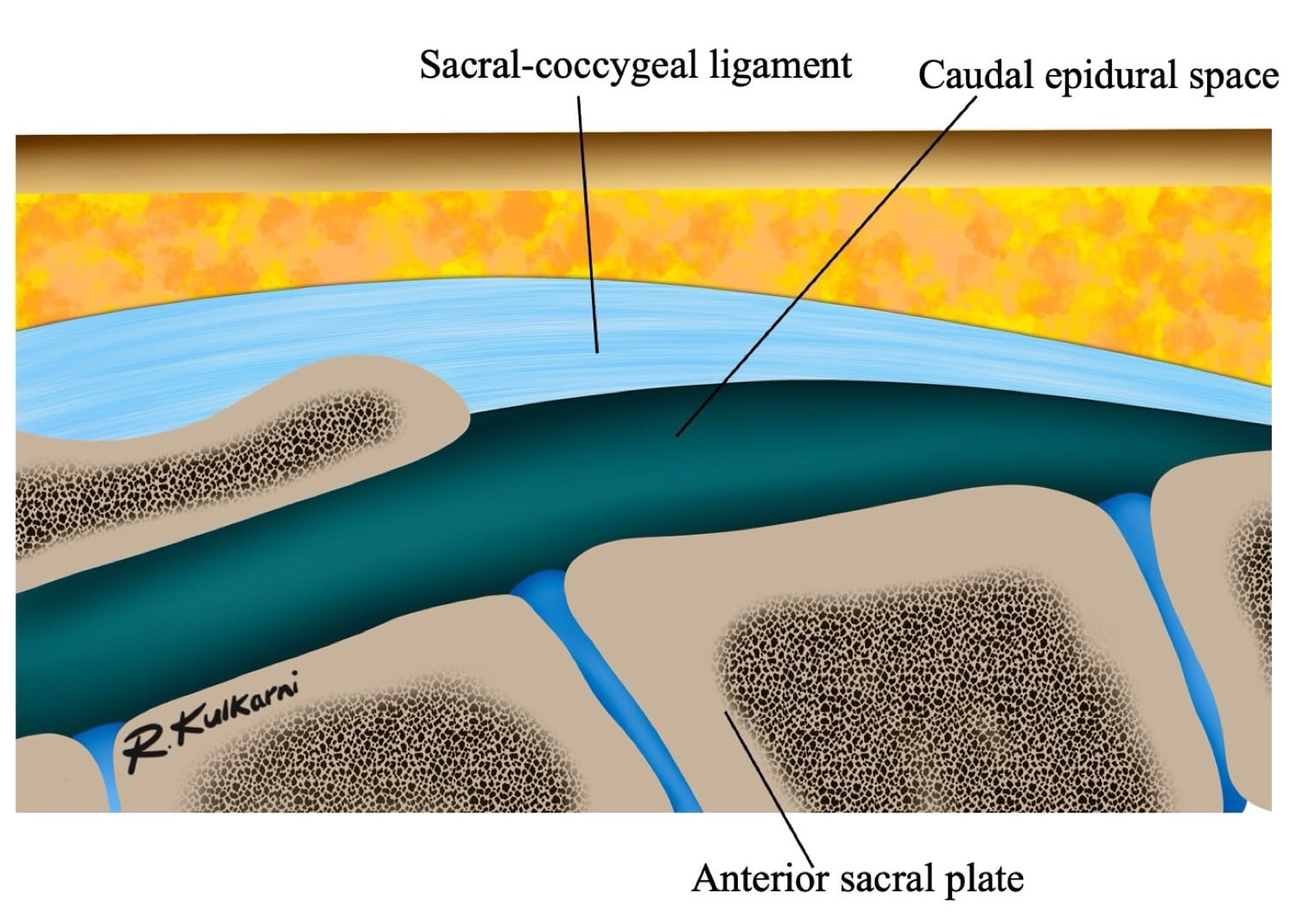

The sacral hiatus, a triangular opening at the lower end of the sacrum, is flanked on either side by bony projections known as the sacral cornua—remnants of the inferior articular processes of the fifth sacral vertebra. This opening is enclosed by the sacrococcygeal ligament. (Figure 2) Within the caudal canal lie epidural fat, the venous plexus, and the sacral and coccygeal nerves that form part of the cauda equina. The dural sac may also extend into this region, although its length is variable and decreases with age. (Figure 3)

The key anatomical differences of the caudal space anatomy among the various age groups is summarized in the table below (Table 1).

| Age Group | Key Anatomy | Relevance to Caudal Block |

| Neonates (0–1 Months) |

|

|

| Infants (1–12 Months) |

|

|

| Toddlers (1–3 Years) |

|

|

| Children (3–12 Years) |

|

|

| Adults (>12 Years) |

|

|

Clinical Relevance

In neonates and infants, the technique is safe and highly reliable, with variations that primarily pose dural puncture risks. As children age, ossification reduces ease, transitioning to adult-like challenges by puberty, where variations contribute to 20%-30% failure rates without imaging guidance. USG improves identification across groups, especially in variants.

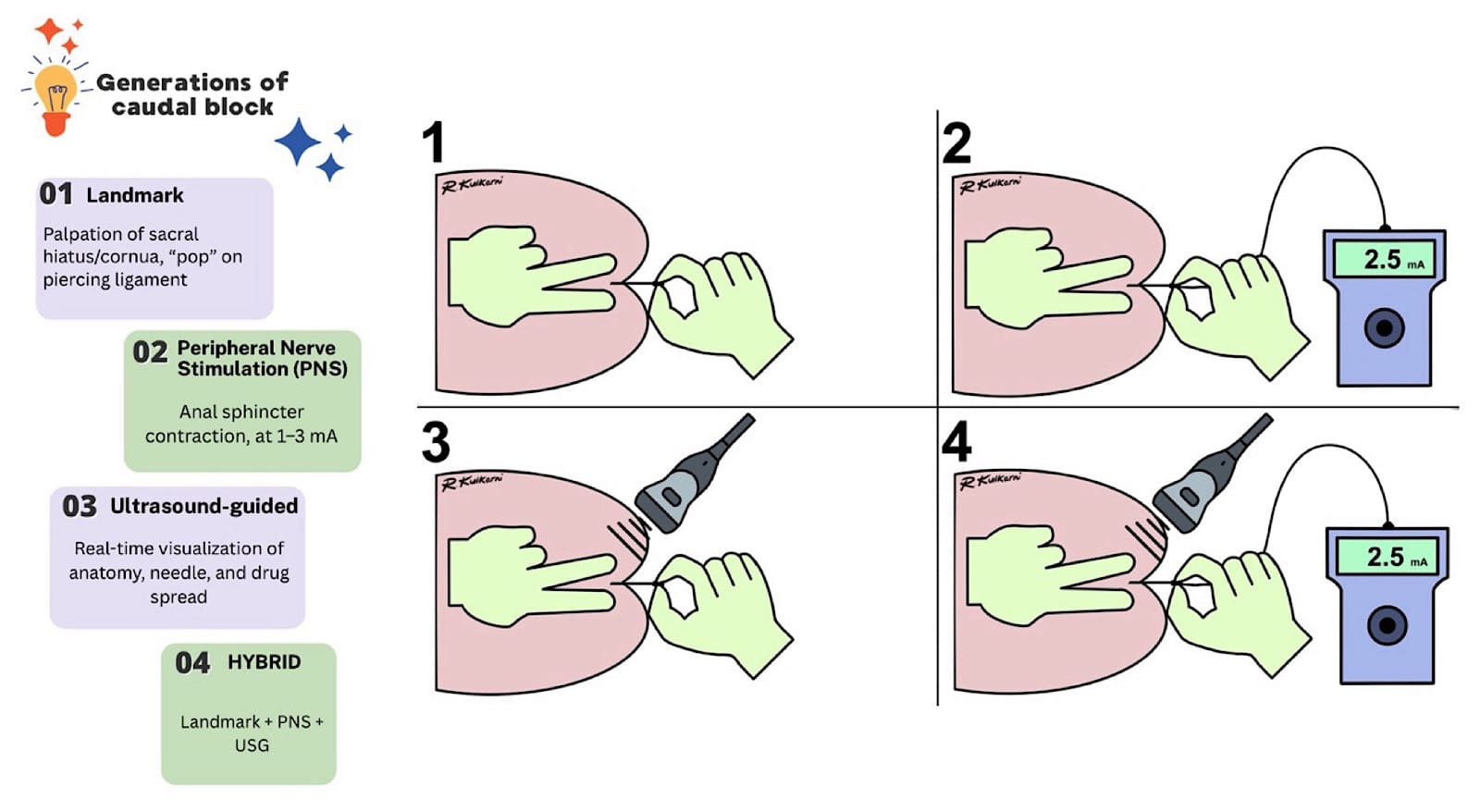

Generations of Caudal Epidural Blockade (Figure 4)

The caudal epidural block has evolved across generations from a landmark-based technique to a current hybrid technique as follows:

- Landmark guided technique where the sacral hiatus/cornua is palpated and a distinct pop is sought for piercing the sacro-coccygeal ligament, marking the needle entry into the caudal space.

- Needle entry into the caudal space is confirmed with nerve stimulator-evoked motor response of anal sphincter contractions at 1-3mA current.

- USG identification of the landmarks and needle entry into the caudal space and confirmation of the drug spread in real time.

- A hybrid technique where all three methods (landmark, peripheral nerve stimulator, and USG) are used to increase the success and enhance safety.

The following tables list the indications and contraindications of the caudal epidural block:

| Surgery Type | Examples |

| Infra-umbilical | Hernia repair, orchidopexy, circumcision, hypospadias repair, and lower limb orthopaedic surgeries |

| Short procedures | Excellent for day-care and ambulatory surgeries |

Clinical Pearl: Cranial spread is inversely proportional to patient age.

| Absolute | Relative |

| Local infection, Coagulopathy | Spinal anomalies (spina bifida, meningomyelocele, tethered cord) Hypotension |

Preparation

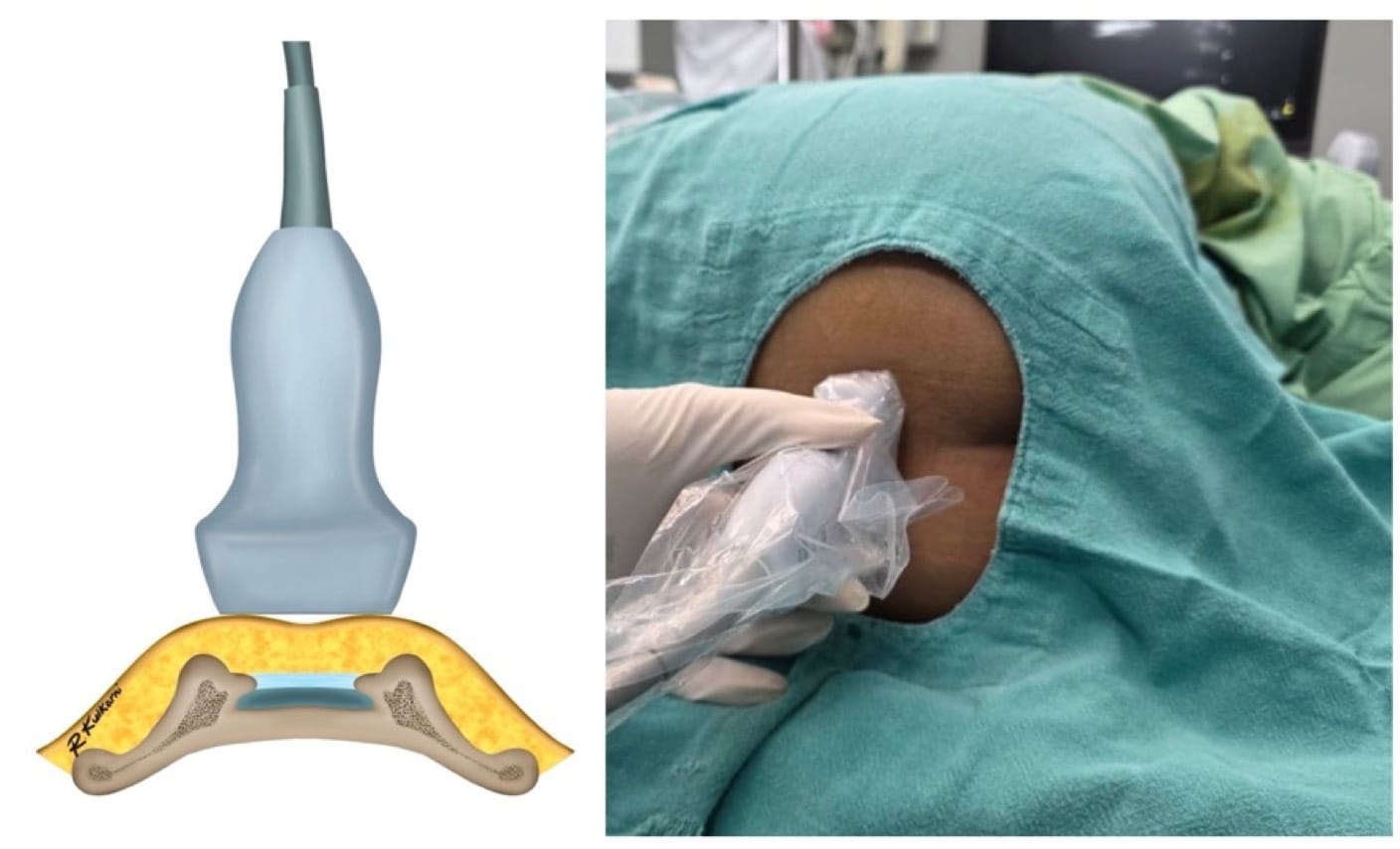

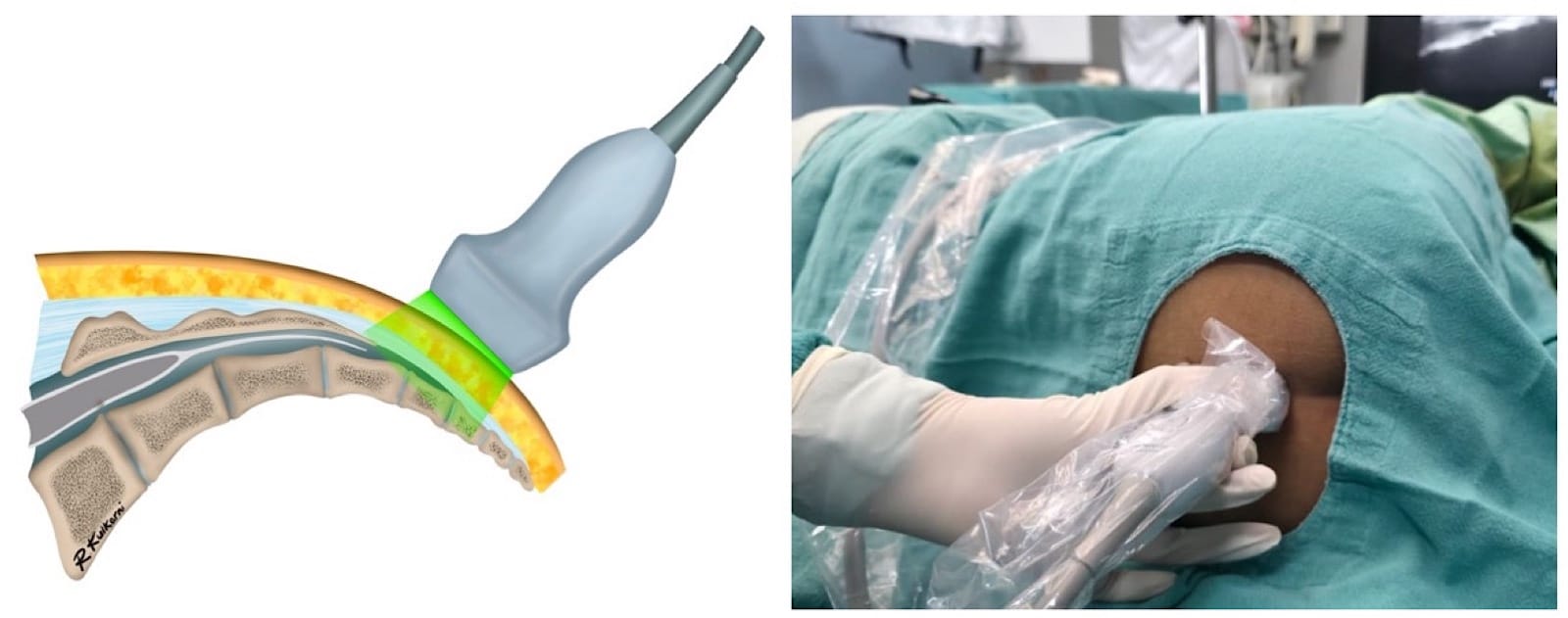

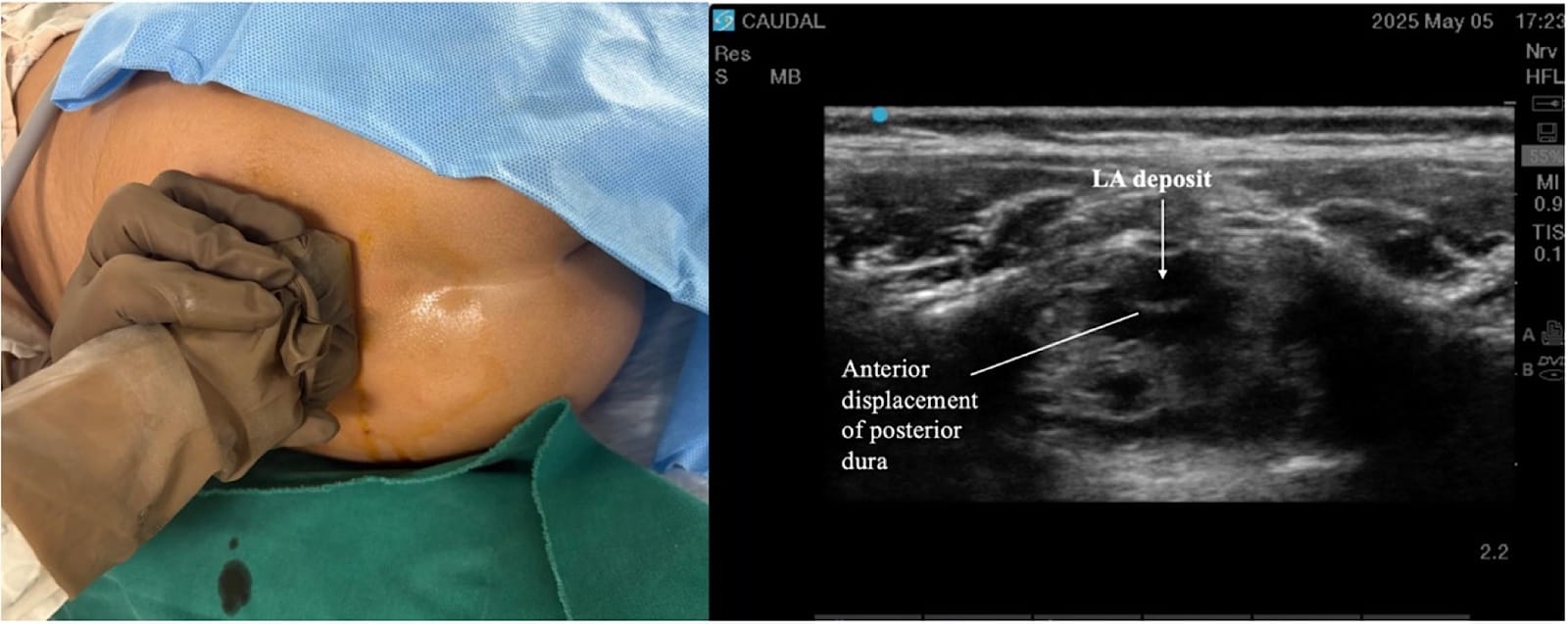

Before the procedure, standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitoring should be instituted, and intravenous access should be secured. All essential resuscitation equipment must be ready. The patient may then be positioned either in the lateral (Figure 4) or prone position according to clinical preference and anatomical considerations. Meticulous aseptic technique is mandatory, including establishing a sterile field and applying a sterile probe cover. Saline is preferred as the coupling medium for USG rather than a gel.

Performing the block

- Landmark Technique (First Generation)

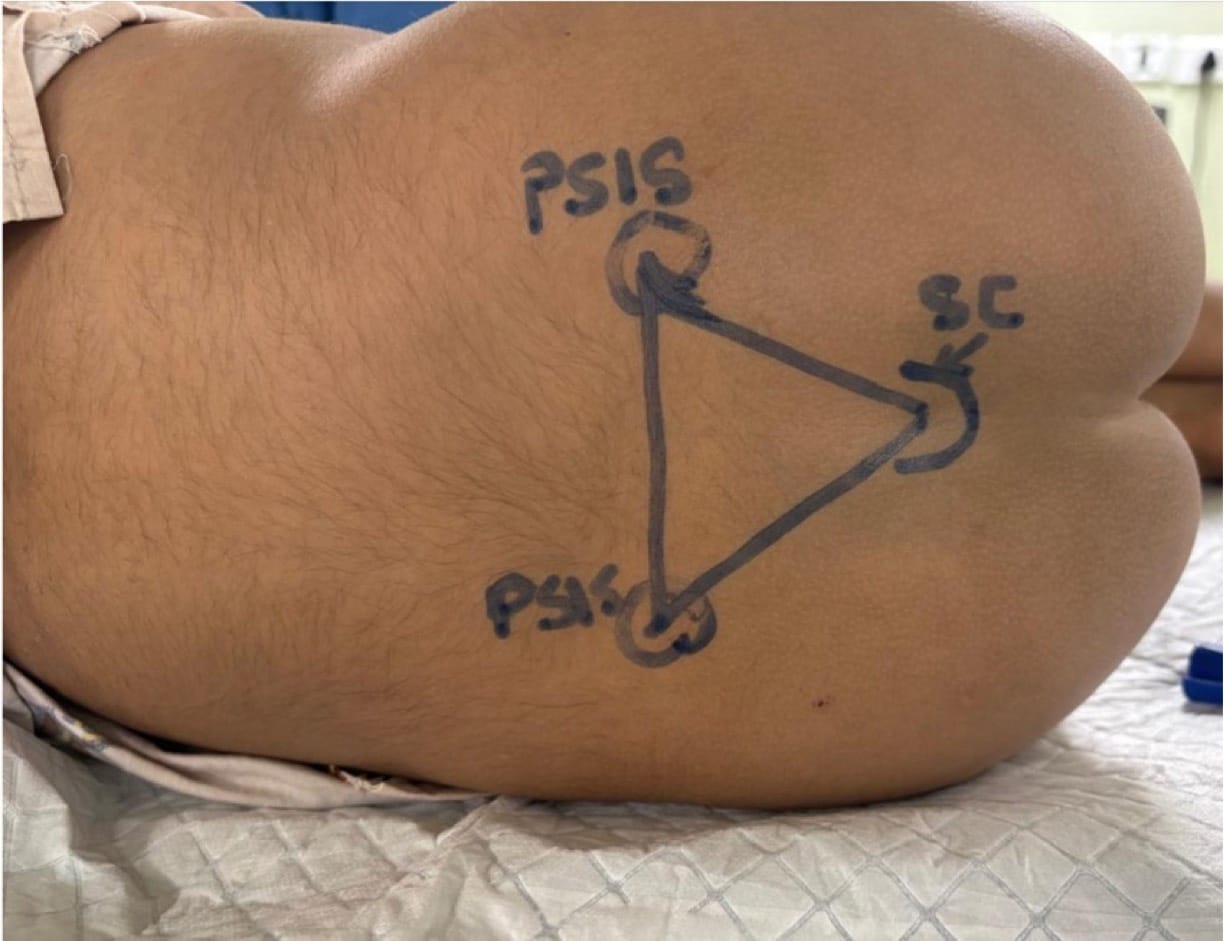

The procedure begins by palpating the posterior superior iliac spine and the sacral cornua. This forms a triangle, the tip of which is an inverted “V” shaped sacral hiatus (Figure 5). The needle is then introduced at an angle of 60-70° at the designated entry point (point A in Figure 6). A characteristic “pop” is typically appreciated as the needle passes through the sacrococcygeal ligament. Following this, the needle is gently flattened to align with the sacral canal (point B in Figure 6). The needle is then advanced an additional 2-3 mm into the caudal space if required. Successful needle tip positioning in the caudal space can be confirmed by the whoosh/swoosh test.

Whoosh/Swoosh Test (air/saline)

Although these tests are described, a successful caudal block can be performed solely using anatomical landmarks and the subjective feel of the pop, followed by the free injection of local anesthetic (LA). However, it is imperative to be aware of these tests.

Whoosh test: A method introduced in 1992 where 2 ml of air is injected into the epidural space, producing a “whoosh” sound heard via a stethoscope to confirm caudal epidural needle placement.14

Swoosh test: A safer refinement in which LA or saline is injected instead of air, creating a “swoosh” sound to verify correct placement while avoiding air-related complications.

Use of air for the whoosh test may result in air embolism, root compression, pneumocephalus, and incomplete analgesia.15,16 Saline is therefore preferred as a swoosh test technique in our practice.

Troubleshooting during landmark-guided caudal block is summarized in Table 4.

| Trouble | Interpretation | Solution |

| Cornua not palpable | Suspect deformity | Use the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) triangle method (Figure 7 ), or use USG |

| Skin and subcutaneous swelling | The needle is too superficial | Stop the injection. Redirect the needle deep. |

| Resistance to injection | Needle too deep, likely hitting the bone or intraosseous | Stop injection, remove and redirect superficially. |

| CSF aspiration | Dural Sac is punctured | Remove and redirect the needle. Don’t advance it to the same length |

| Blood aspiration | Needle tip in a vessel | Remove and redo the procedure |

- Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (Second Generation)

The needle is first introduced according to standard landmark-guided techniques. After the characteristic “pop” is appreciated, an insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator is used to advance the procedure. Adequate placement is confirmed by observing anal sphincter contraction in response to stimulation at 1-3 mA. (Figure 8)

Troubleshooting during peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS)-guided caudal block is summarized in Table 5.

| Trouble | Interpretation | Heading Missing |

| Response seen at very low current (<1 mA) | Indicates dural puncture | Stop, redirect the needle |

| No response | Ensure the complete circuit → electrode well-connected, if still no response | Slightly advance the needle further |

Clinical Pearl

The perpendicular needle insertion technique may also be used to access the caudal epidural space, and the needle insertion is halted after the subjective feel of the pop. (Figure 9)

- Ultrasound-Guidance (Third Generation)

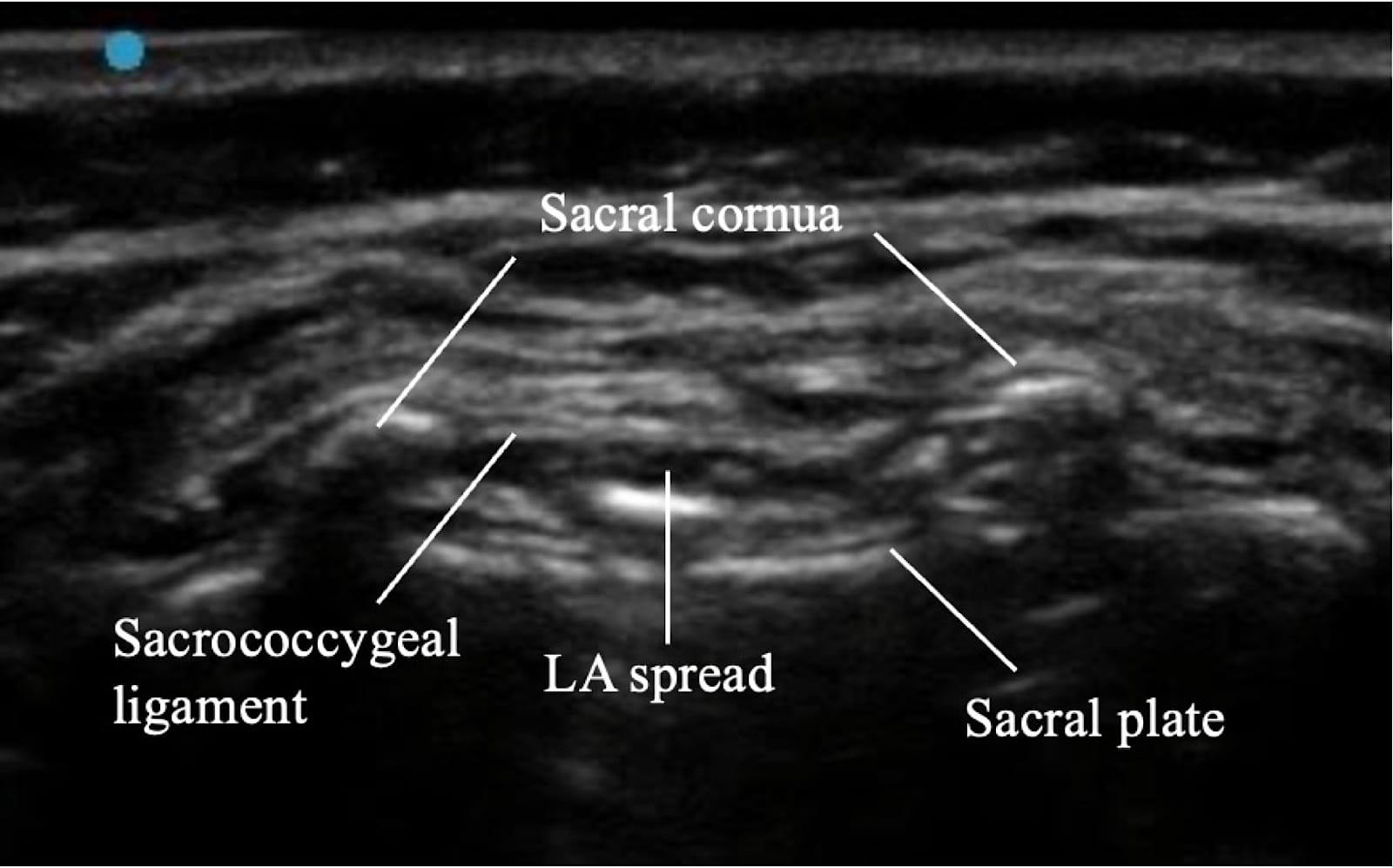

Proper ergonomic positioning is essential, with the ultrasound screen and procedural field aligned along the operator’s natural line of sight. This facilitates precision and reduces operator strain. A high-frequency linear or hockey stick ultrasound transducer is used to optimize visualization of the superficial sacral anatomy. Key structures, including the sacral cornua, the sacrococcygeal ligament, and the caudal canal, should be clearly identified on the ultrasound image. The needle is then advanced in plane under continuous real-time USG to ensure accurate trajectory and safe entry into the caudal space. Alternatively, out-of-plane needle insertion during transverse scanning is an option. Adequate placement is confirmed by cephalad drug spread, dura displacement, and posterior epidural expansion. (Figures 10–15)

Troubleshooting during the USG caudal block is summarized in Table 6.

| Problem | Cause | Fix |

| Needle tip not seen | Lost plane | In-plane approach, rock probe, saline bolus |

| No epidural spread | Too shallow/deep | Adjust needle position, confirm with flush |

| Resistance to injection | Bone/ligament | Stop injection, reposition the needle |

| Blood aspiration | Venous puncture | Withdraw, redirect, always aspirate before re-injection |

Drugs and Dosing for caudal blocks are summarized in Tables 7–9.

| Drug | Dose (mg/kg) | Notes |

| Bupivacaine 0.25% | 2 | The maximum safe dose is essential. |

| Ropivacaine 0.2% | 2 | Lower toxicity |

| Lidocaine 2% with adrenaline (1:200,000) | 5 | Shorter duration, rapid onset |

| Drug | Dose (mcg/kg) | Notes |

| Clonidine | 1-2 | Bradycardia, Hypotension |

| Morphine | 10-30 | Reduced gastrointestinal motility, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression. To be used with caution, the patient should be monitored in the high dependency unit for 24 hours at least. |

| Desired Dermatome | Dosages | LA Concentration |

| Sacral dermatomes | 0.5 ml/kg | (Levo) Bupivacaine 0.125-0.25% |

| Lumbar dermatomes | 1.0 ml/kg | or |

| Lower thoracic dermatomes | 1.25 ml/kg | Ropivacaine 0.1-0.375% |

Clinical Pearls

- Although the administered LA volume may vary, the dosage expressed in mg/kg remains constant; therefore, the patient consistently receives a dose within the established safety margin.

- In neonates and infants younger than 3 months, LA spread may extend to the lower thoracic dermatomes, depending on the injectate and volume.

- Test dose (with adrenaline 1:200,000): Heart rate ↑ >10 bpm / Systolic blood Pressure ↑ >15 mmHg / ECG ST–T changes indicates positive test. Intravascular drug injection/Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST) anaesthesia systemic toxicity should be suspected.

Safety Pearls

- If USG is available, scout scanning of the caudal space is suggested before proceeding with the landmark guided technique to rule out perineural (Tarlov) cysts, which can be a reason for failure or inadvertent intrathecal injection.18 This consideration becomes particularly crucial when there are clinical indicators of anatomical deviation, such as cutaneous discoloration, the presence of a hair tuft, or a midline skin dimple over the lumbosacral region.

- Always aspirate before injection.

- Inject slowly, 0.1 to 0.2 ml per kg aliquots and never forcefully.

- Use USG in neonates/abnormal anatomy.

- Use incremental injection with monitoring.

- Document block.

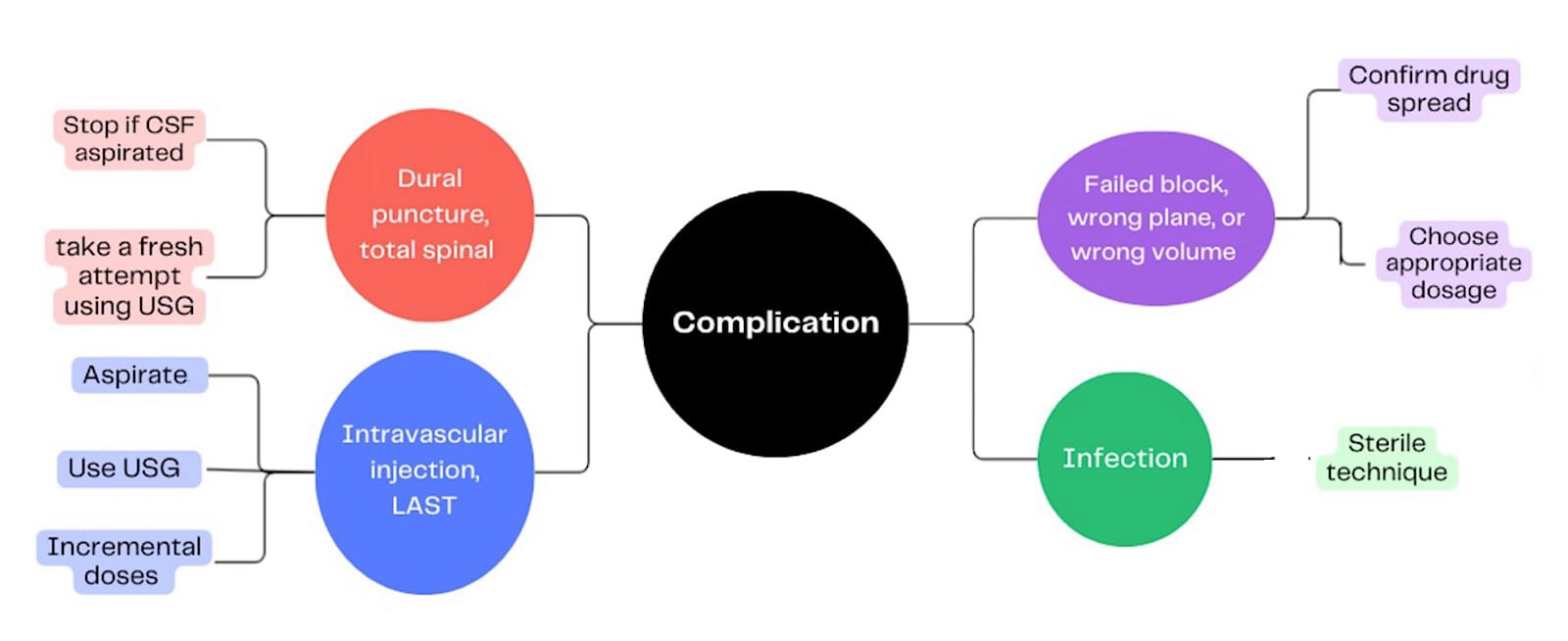

Complications

Possible complications of a caudal block include dural puncture with potential total spinal anesthesia, inadvertent intravascular injection leading to local anaesthetic systemic toxicity, block failure due to incorrect needle placement or dosing errors, nerve injury, other tissue injury, bleeding complications, and infection resulting from inadequate aseptic technique. (Figure 16)

The following table compares and contrasts the caudal block techniques. In experienced hands, the success rate across modalities is the same.16

| Feature | Landmark | PNS | USG |

| Nature | Subjective | Objective (motor response, indirect) | Objective (direct visualization) |

| Complexity | Simple | Moderate | Higher skill |

| Equipment | None | Stimulator + insulated needle | USG + sterile setup |

| Confirmation | Smooth injection, “pop”/ Whoosh test | Anal sphincter contraction | Drug spread, dura displacement |

| Advantages | Quick, simple | Detects dural puncture, adds objectivity | Safest, shows anatomy and spread |

| Limitations | Variable accuracy | Needs equipment and an intact circuit | Needs USG + training |

| Success Rate | Moderate | High | Highest |

At a Glance – Quick Poster (Figure 17)

This technique is simple, has been here for decades, and is here to stay!

References

- Campbell MF. Caudal anesthesia in children. J Urol 1933;30(2):245-50.

- Trotter M. Variations of the sacral canal: their significance in the administration of caudal analgesia. Curr Res Anesth Analg 1947;26(5):192-202.

- Veyckemans F, Van Obbergh LJ, Gouverneur JM. Lessons from 1100 pediatric caudal blocks in a teaching hospital. Reg Anesth 1992;17(2):119-25.

- MacDonald A, Chatrath P, Spector T, et al. Level of termination of the spinal cord and the dural sac: a magnetic resonance study. Clin Anat 1999;12(3):149-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1999)12:3<149::AID-CA1>3.0.CO;2-X

- Koo BN, Park JH, Kim JY, et al. Determination of the optimal angle for needle insertion during caudal block in children using ultrasound imaging. Paediatr Anaesth 2009;16(10):1013-17.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.01905.x

- Shin SK, Hong JY, Kim WO, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of the sacral area and comparison of sacral interspinous and hiatal approach for caudal block in children. Anesthesiology 2010;111(6):1135-40. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bc6dd4

- Fortuna A. Caudal analgesia: a simple and safe technique in paediatric surgery. Br J Anaesth1967;39(2):165-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/39.2.165

- Aggarwal A, Kaur H, Batra YK,et al. Anatomic consideration of caudal epidural space: a cadaver study. Clin Anat 2009;22(6):730-7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.20832

- Armitage EN. Regional anaesthesia in paediatric practice. Update in Anaesthesia. 1989;1:1-6.

- Sekiguchi M, Yabuki S, Satoh K, et al. An anatomic study of the sacral hiatus: a basis for successful caudal epidural block. Clin J Pain 2004;20(1):51-4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200401000-00010

- Joo J, Kim J, Lee J. The prevalence of anatomical variations that can cause inadvertent dural puncture when performing caudal nerve block in Koreans: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. Anaesthesia2010;65(2):179-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06188.x

- Crighton IM, Barry BP, Hobbs GJ. A study of the anatomy of the caudal space using magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Anaesth 1997;78(4):391-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/78.4.391

- Igarashi T, Hirabayashi Y, Shimizu R, et al. Investigation of the epidural space using epiduroscopy in pediatric patients. Anesthesiology. 1997;86(5):1033-7. https://doi.org/

- Lewis MP, Thomas P, Wilson LF, et al. The ‘whoosh’ test. A clinical test to confirm correct needle placement in caudal epidural injections. Anaesthesia 1992;47:57e8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1992.tb01957.x

- Bosenberg A. Benefits of regional anesthesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2012;22:10-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03691.x

- Martin J. Regional anaesthesia in neonates, infants and children: an educational review. Eur J Anaesth2015;32:289-97. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000000239

- Ponde V, Singh N, Nair A, et al. Comparison of landmark-guided, nerve stimulation-guided, and ultrasound-guided techniques for pediatric caudal epidural anesthesia: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2021;38(2):114-18. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000001003

- Ponde V, Bedekar V. Encountering caudal cyst on ultrasound: what do we do? Indian J Anaesth 2017; 61: 685. https://doi.org/10.4103/ija.IJA_144_17