Collaborative Excellence: The Multi-Society Post-Dural Puncture Headache Guidelines

Cite as: Uppal, V. Collaborative excellence: the multi-society post-dural puncture headache guidelines. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2024;49. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110124.007.

Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is a known complication that can occur after an accidental dural puncture during epidural analgesia or a deliberate dural puncture after a lumbar puncture. While the headache may subside within 2 weeks, its intensity can significantly disrupt daily activities. PDPH is also linked to complications such as subdural hematoma, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and cranial nerve dysfunction.

Recently, I had the privilege and honor of leading the development of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on PDPH, a consensus report from a multi-society international working group.1,2 These guidelines were developed with contributions from 21 delegates (Figure 1) from six professional societies, including the ASRA Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anesthesia (ESRA), the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP), the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Interventional Headache Society.

Why Are These Guidelines Necessary?

Improving care and enhancing patient safety is crucial, given that PDPH can be a significant complication following neuraxial procedures. These guidelines are essential as they offer a comprehensive framework for clinicians to prevent, diagnose, and manage PDPH.

By adhering to these guidelines, clinicians can:

- Reduce the incidence of PDPH. Identify and address risk factors before procedures.

- Improve diagnosis. The guidelines offer clear diagnostic criteria for PDPH, aiding clinicians in accurately identifying and diagnosing the condition.

- Optimize management. Recommendations cover various management approaches, including conservative measures, blood patches, and other interventions, helping clinicians choose the most appropriate treatment for each patient.

How Were the Guidelines Developed?

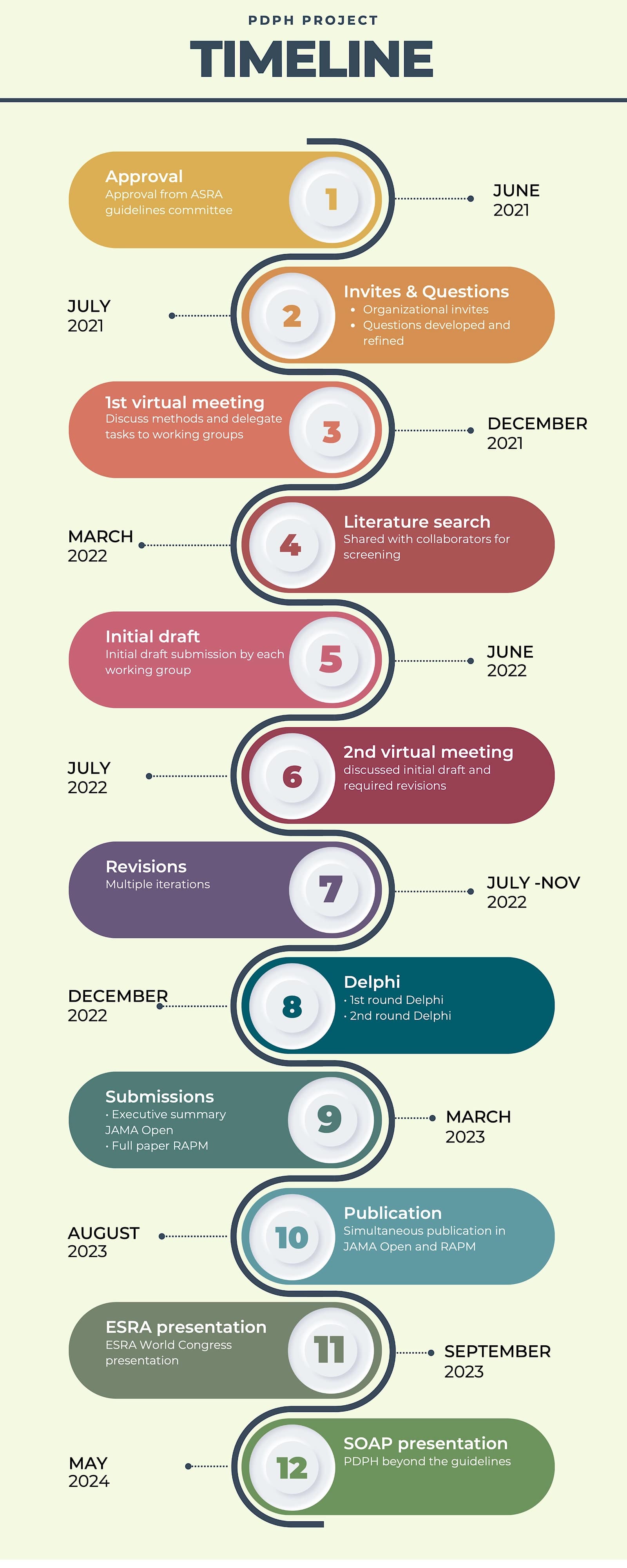

The guidelines were developed rigorously and transparently, incorporating expert input and carefully evaluating available evidence. (Figure 2)

In April 2021, Dr. Samer Narouze and I obtained approval from ASRA Pain Medicine’s guidelines committee and board of directors. The ASRA Pain Medicine executive director, Angela Stengel, contacted the leaders of each society to nominate representatives for the guideline.

The development process involved several key steps:

- Formation of the committee. An expert committee was established, co-chaired by Vishal Uppal and Samer Narouze, and included representatives from the participating societies.

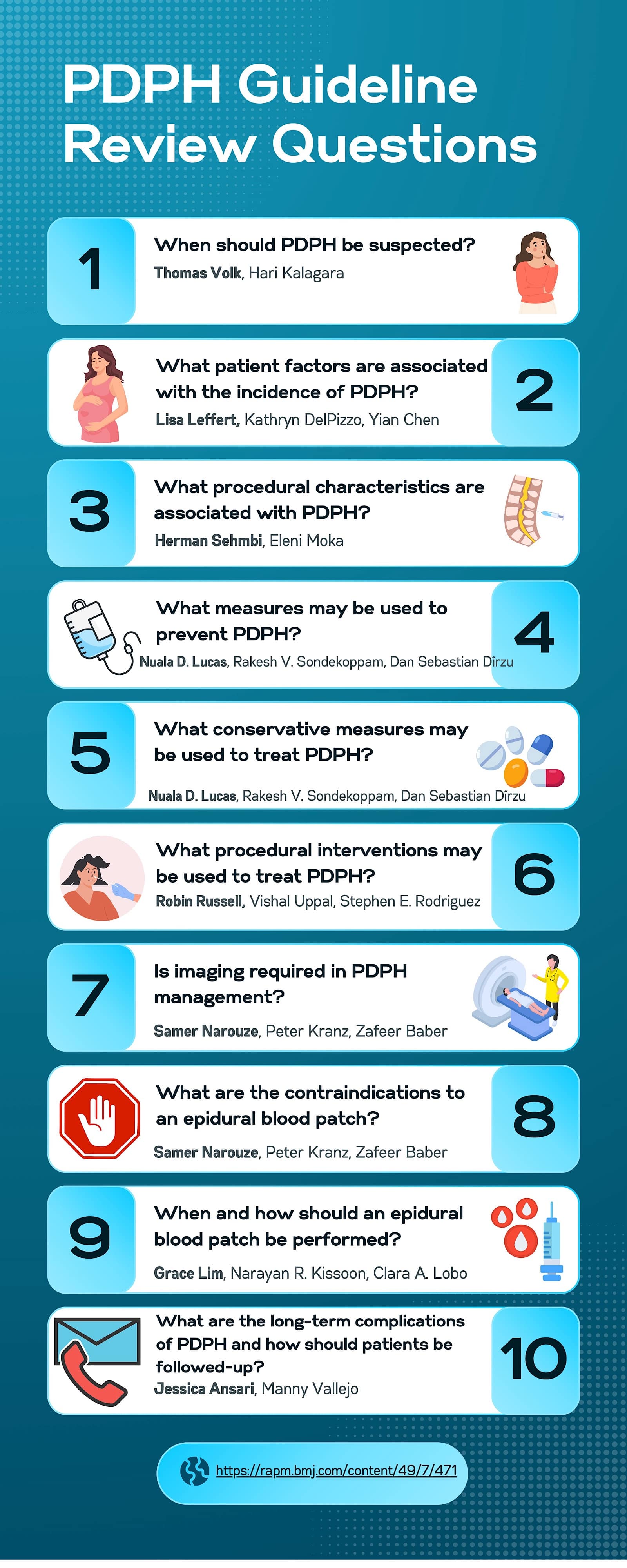

- Development of review questions. The committee created 10 questions focusing on PDPH prevention, diagnosis, and management. These questions were refined during conference calls, with input from committee members and stakeholders. Figure 3 presents the 10 PDPH review questions and their corresponding writing groups with team leads indicated in bold.

- Literature search and review. A health sciences librarian conducted a comprehensive literature search for each review question in MEDLINE All (Ovid). Results were imported into Covidence projects for deduplication, screening, and data extraction.

- Development of recommendations. Contributors were divided into 10 writing groups, each with a designated leader. Each group submitted a structured narrative review, and recommendations were graded according to the United States Preventative Services Task Force grading of evidence guidelines.

- Voting and consensus. The interim draft was shared with all collaborators, who voted anonymously on each recommendation using a modified Delphi approach. Two rounds of voting were conducted with recommendations achieving a pre-specified level of consensus among experts.

- Final approval. The final manuscript was approved by all collaborators, the ASRA Pain Medicine Board of Directors, and participating societies.

The editing team consisting of Drs. Robin Russell, Vishal Uppal and Rakesh V. Sondekoppam reviewed and revised the submissions, creating an interim draft. The executive summary manuscript was submitted to the JAMA Open in March 2023, followed by the complete paper submission to the Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (RAPM) journal in June 2023. Both papers and the accompanying editorials are available as free downloads.3,4 Additionally, infographics summarizing the key findings of the guidelines were published in the RAPM journal.5

These guidelines are essential as they offer a comprehensive framework for clinicians to prevent, diagnose, and manage PDPH.

The Summary of Recommendations is as follows:

When should PDPH be suspected?

- Suspected: If headache or neurological symptoms occur within 5 days of a neuraxial procedure, relieved when lying flat (Moderate Certainty).

- Recommendation: Inpatients should be evaluated for PDPH; outpatients should report symptoms (Grade A; High Certainty).

What patient factors are associated with the incidence of PDPH?

- Age: In the adult population, younger age may be associated with an increased risk of PDPH (High Certainty).

- Sex: Female sex is associated with an increased risk of PDPH (High Certainty).

- Body mass index: Evidence does not suggest that BMI has a consistent correlation with an increased risk of PDPH (Moderate Certainty).

- Headache: A history of headaches may be associated with an increased risk of PDPH (Moderate Certainty).

What procedural characteristics are associated with PDPH?

- Needle type: Compared to cutting needles, non-cutting spinal needles are associated with decreased PDPH risk (High Certainty).

- Needle size: When using cutting needles, narrower gauge needles reduce the risk of PDPH (High Certainty).

What measures may be used to prevent PDPH?

- Intrathecal catheter: This may be considered after accidental dural puncture (Grade C; Low Certainty). For guidance on managing intrathecal catheter placement following inadvertent dural puncture in the obstetric population, please refer to the latest guidelines from the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association.6

- Prophylactic epidural blood patch (EBP): It is not routinely recommended (Grade I; Low Certainty).

- Routine injections: Routine injection of any substance intrathecally or epidurally is not recommended for prevention (Grade I; Low Certainty).

What conservative measures may be used to treat PDPH?

- Bed rest: It is not routinely recommended, though it can provide temporary relief (Grade C; Low Certainty).

- Hydration: Oral fluids are preferred; IV if necessary (Grade C; Low Certainty).

- Multimodal analgesia: Acetaminophen, NSAIDs recommended (Grade B; Low Certainty); opioids only short-term as needed (Grade C; Low Certainty).

- Caffeine: It may be offered in the first 24 hours (Grade B; Low Certainty).

- Other medications: Hydrocortisone, triptans, and others are not routinely recommended (Grade I; Low Certainty).

What procedural interventions may be used to treat PDPH?

- Sphenopalatine Ganglion Block: It is not routinely recommended (Grade I; Low Certainty).

- Greater Occipital Nerve Block: It may be offered for PDPH following narrower gauge needles, but headaches may recur (Grade C; Moderate Certainty).

- Acupuncture, epidural morphine: It is not recommended (Grade I/D).

- Epidural saline: There is a temporary benefit, but not long-lasting (Low Certainty).

- Epidural colloids and fibrin glue: They are not routinely recommended, and fibrin glue is reserved for refractory cases (Grade I).

Is imaging required in PDPH management?

- Imaging: It may be considered if non-orthostatic headache, late-onset, or neurological symptoms are present (Grade C/B).

What are the contraindications to an EBP?

- Antithrombotics/low platelets: Follow society guidelines for neuraxial procedures; there is a low risk of hematoma with platelets ≥70,000 x 106/L (Moderate Certainty).

- Prophylactic antibiotics: They are not recommended (Low Certainty).

When and how should an EBP be performed?

- EBP: Consider for PDPH refractory to conservative therapy and impairing daily life (Grade: B; Moderate Certainty).

- Timing: A repeat may be necessary if performed within 48 hours (Grade B).

- Volume: 15-20 mL of blood recommended (Low Certainty); avoid injecting >30 mL.

- Technique: Aseptic technique and slow injection (Grade B).

What are the long-term complications of PDPH, and how should patients be followed up?

- Complications: PDPH is associated with chronic headaches, backaches, depression, and cranial nerve palsies (Moderate Certainty).

- Follow-up: Continue until headache resolves; urgent imaging if symptoms worsen (Grade B).

The guidelines were featured in presentations at the ESRA World Congress in September 2023 and the ASRA Spring Meeting in March 2024. A dedicated “PDPH Beyond the Guidelines” session was held at Denver’s SOAP Annual Meeting in May 2024.

This project exemplifies a significant collaboration, bringing together 21 experts from six different professional societies and achieving completion within a remarkable timeframe. The comprehensive guidelines document spanned nearly 20,000 words and included over 450 references, reflecting these busy clinicians’ commendable dedication and effort.

Given the lack of uniformity and limited evidence in current approaches to treating PDPH, we hope these guidelines offer clinicians a structured framework to assess risk, confirm diagnoses, and adopt a more systematic approach to management.

References

- Uppal V et al. Consensus practice guidelines on post-dural puncture headache from a multi-society, international working group: a summary report. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6(8): e2325387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25387

- Uppal V et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on post-dural puncture headache: a consensus report from a multi-society international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2024;49(7):471-501. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2023-104817

- Bicket MC, Peahl A, and Gaiser RR. Improving the management of postdural puncture headache- an international clinical guideline and call for better evidence. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6(8):e2325348. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25348

- Landau R, Weiniger CF. Postdural puncture headache after intentional or unintentional dural punctures: time to think about risk reduction and acknowledge the burden of sequelae. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2024; 49(1): 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2023-104945

- Uppal V et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on post-dural puncture headache: infographics. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2024;49(7): 502-4. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2024-105280

- Griffiths SK, Russell R, Broom MA, et al. Intrathecal catheter placement after inadvertent dural puncture in the obstetric population: management for labour and operative delivery. Guidelines from the Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association. Anaesthesia 2024. https://doi:10.1111/anae.16434