Problem-Based Learning Discussion (PBLD) Collaborative Series: Perioperative Management of Spine Surgery

Cite as: Problem-Based Learning Discussion (PBLD) Collaborative Series: Perioperative Management of Spine Surgery. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2024;49. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra080124.004.

With contributions from the following societies:

/collab-asra-logo-stacked-in-blue-box-sq.png?sfvrsn=576fe14d_1)

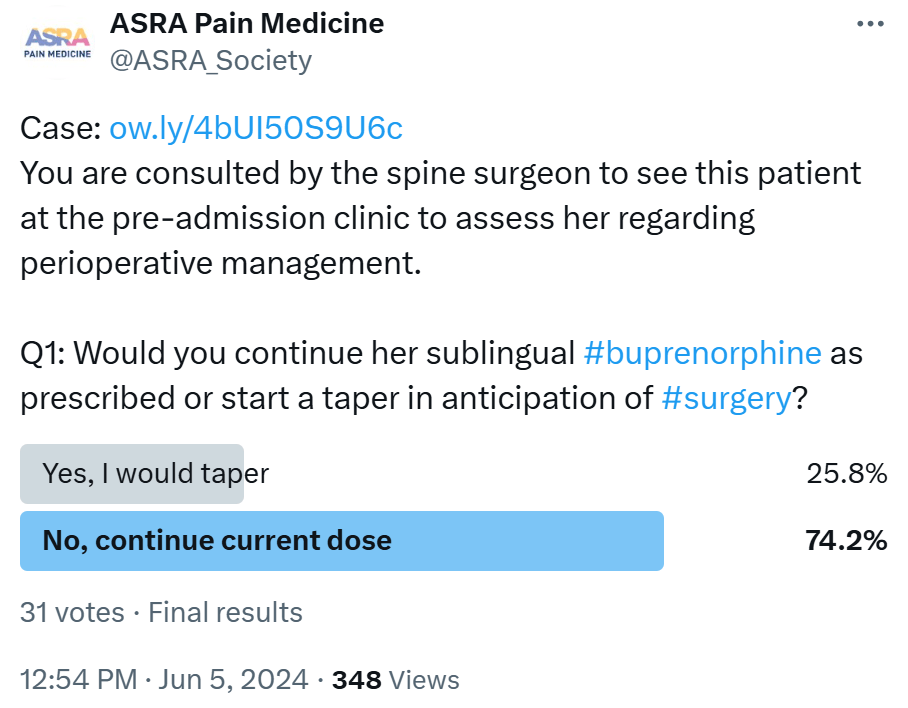

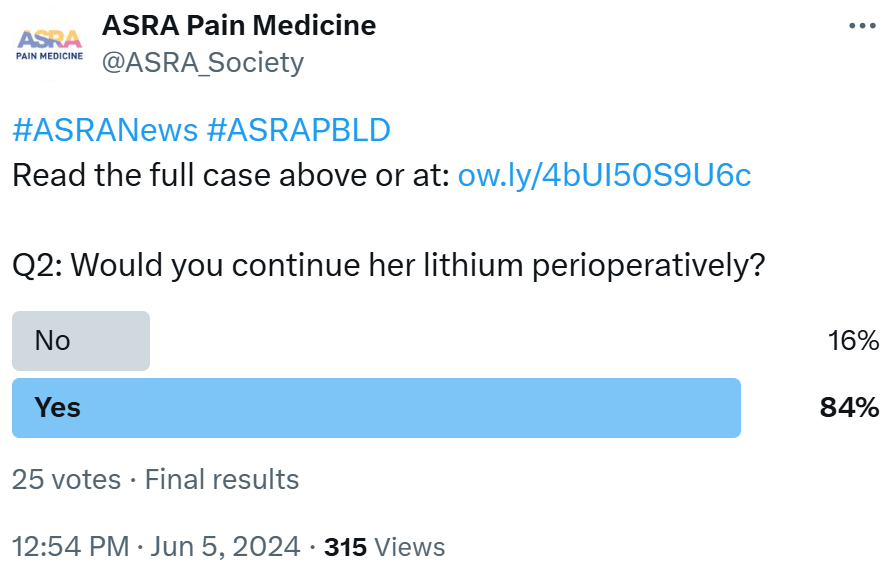

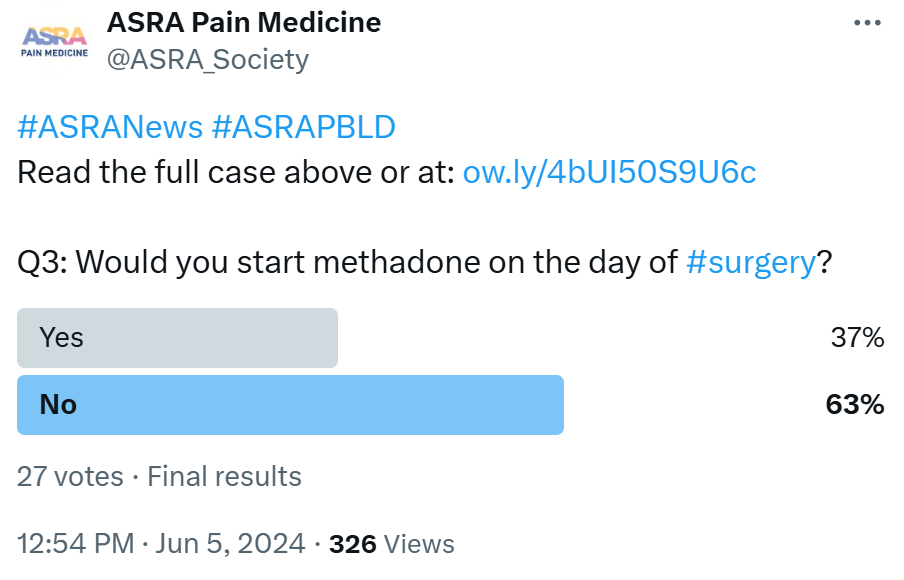

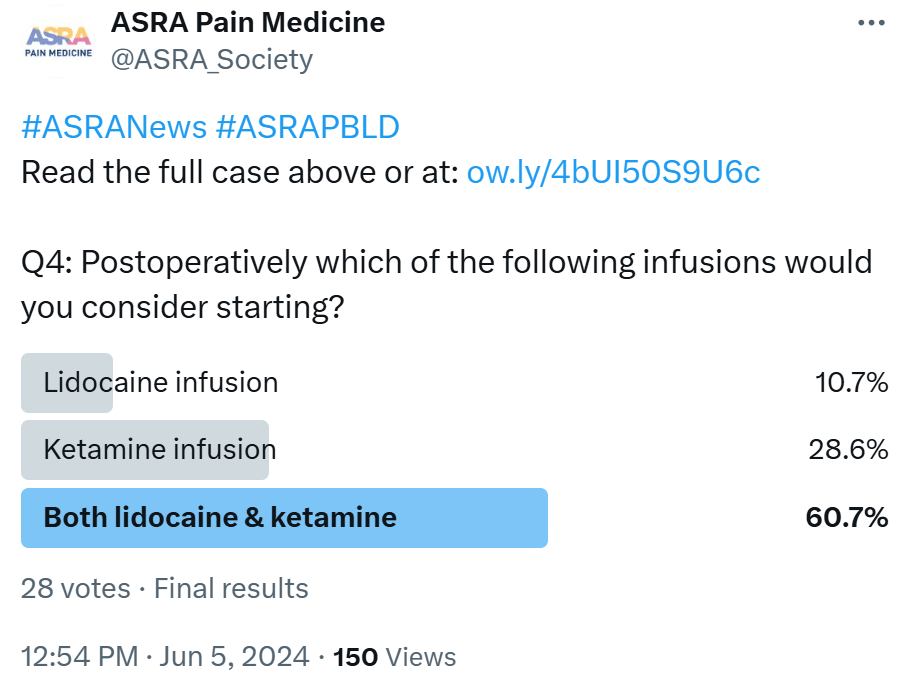

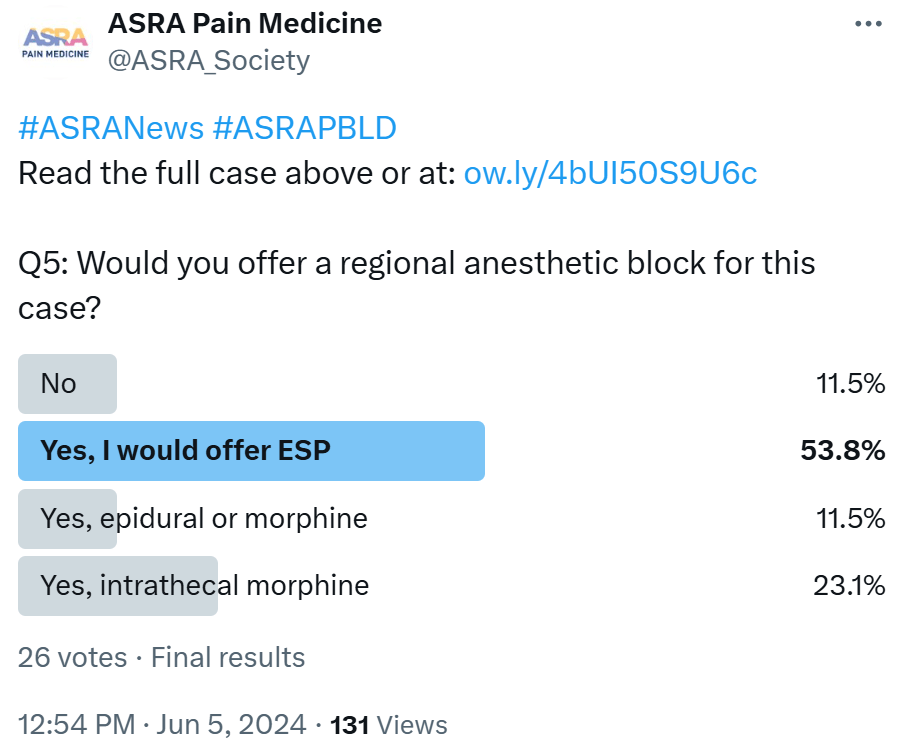

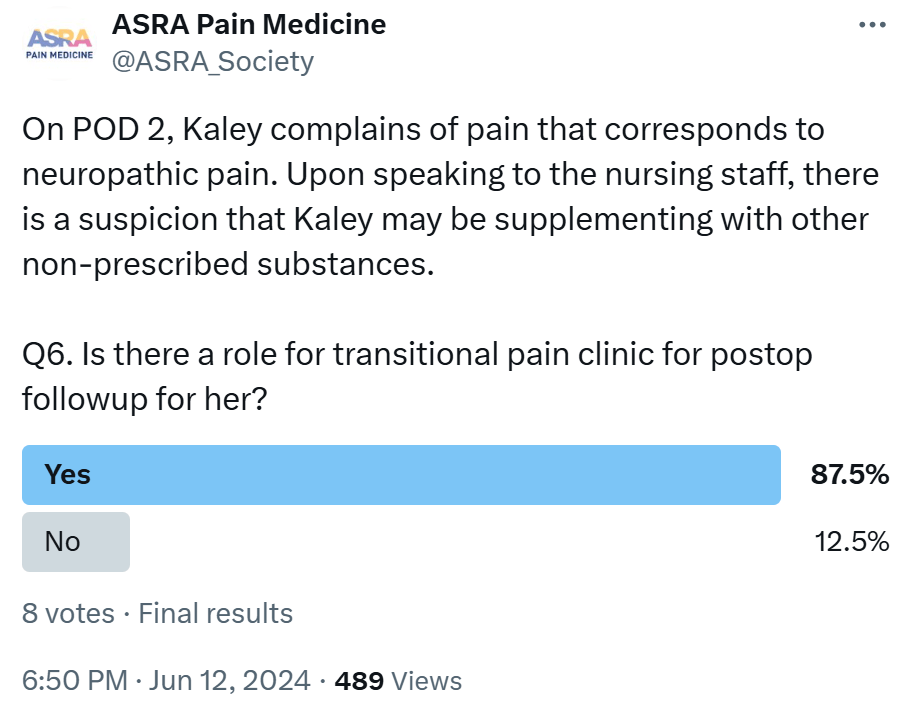

Welcome to the latest ASRA Pain Medicine News Problem-Based Learning Discussion (PBLD). This PBLD was an international collaborative effort with representatives from the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia & Pain Therapy (ESRA), Latin American Society of Regional Anesthesia (LASRA), Asian & Oceanic Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine (AOSRA-PM), African Society for Regional Anesthesia (AFSRA), and Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society (CAS). The case and questions were also shared on the ASRA Pain Medicine X/Twitter account (@ASRA_Society) to get input from the community at large. Do you have a case worthy of discussion? Please send cases you would like to see in this format to [email protected].

Case Description

Kaley is a 28-year-old, 105kg female with a history of scoliosis and opioid-use disorder, currently on sublingual buprenorphine (8 mg) three times a day, which was prescribed in the community. In addition, she admits to using other recreational drugs, such as cannabis, maybe a joint a day. She uses a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine for obstructive sleep apnea, although there is a question regarding compliance. She also has bipolar disorder with anxiety, chronic migraine, and fibromyalgia, as well as fatty liver (FL) disease. Her current medications are lithium, amitriptyline, and sumatriptan, together with her pain medication. She is scheduled for instrumentation and fusion from T2 to L2 of her spine in the prone position under general anesthetic.

The spine surgeon consults you to see this patient at the pre-admission clinic to assess her regarding perioperative management.

Part 1: Medical History and Preoperative Assessment

- What salient points must you consider regarding her medical history when seeing her in the pre-admission clinic? Could you also comment on her list of medications?

/collab-asra-logo-stacked-in-blue-box-sq.png?sfvrsn=576fe14d_1)

ASRA (Lynn Kohan, MD) As a pain medicine physician, it is important to recognize risk factors for uncontrolled pain

in the perioperative period. Risk factors in patients undergoing spine surgery have been noted to include several aspects related to the patient’s medical history, including pre-existing chronic pain (fibromyalgia and migraines), chronic

opioid use (buprenorphine), psychosocial risk factors (anxiety), and female gender.1 These risks should be discussed with the patient, but it is necessary to provide reassurance that there are many options to control her pain despite

her risk factors.

ASRA (Lynn Kohan, MD) As a pain medicine physician, it is important to recognize risk factors for uncontrolled pain

in the perioperative period. Risk factors in patients undergoing spine surgery have been noted to include several aspects related to the patient’s medical history, including pre-existing chronic pain (fibromyalgia and migraines), chronic

opioid use (buprenorphine), psychosocial risk factors (anxiety), and female gender.1 These risks should be discussed with the patient, but it is necessary to provide reassurance that there are many options to control her pain despite

her risk factors.

Additionally, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of the severity of her opioid use disorder (OUD). It would be important to understand how long she has been treated with medication for OUD (MOUD) and to obtain the name of her prescribing clinician. It would be valuable to clarify if she is prescribed buprenorphine solely for OUD or if she is being treated for comorbid pain and OUD. Her current TID dosing regimen suggests she is being treated for both conditions.

ESRA (Clara Lobo, MD) Kaley presents with a complex medical history comprising several pertinent factors that necessitate thorough evaluation:

- She is a young female with psychiatric disorders and chronic pain conditions, which place her at a higher risk for postoperative complications. It is important to determine Kaley's BMI as obesity is associated with increased perioperative risks: potentially difficult airway, altered drug pharmacokinetics requiring adjustments in drug dosing to achieve optimal anesthesia depth and postoperative pain control, and respiratory complications, including hypoventilation and atelectasis, necessitating vigilant monitoring and proactive respiratory support.

- Substance use disorder managed with sublingual buprenorphine necessitates meticulous counseling aimed at reducing opioid intake before surgery. Pain management strategies should be methodically crafted to mitigate the risk of suboptimal pain relief, thereby minimizing postoperative discomfort and the potential for opioid withdrawal. Safety concerns related to drug tolerance (eg, to opioids) that necessitate higher doses with higher risks of potential adverse events.

- It is essential to screen for signs and symptoms of acute intoxication of recreational drugs, complications of substance abuse, and details pertinent to last consumption. Defining which drugs were taken via what route and the amount of drug(s) last consumed, as well as timing, are important to establish. These drugs can interfere with the normal conduction of anesthetic drugs (increased dose of propofol), causing prolonged emergence, post-operative sedation, and other unpredictable effects.2

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) increases the risk of perioperative complications, such as airway obstruction, hypoxemia, and postoperative respiratory failure, and it is imperative to assess compliance and therapeutic efficacy. Anesthesia management should focus on maintaining airway patency and adequate oxygenation.3

- Psychiatric disorders,4 such as bipolar disorder, anxiety, and substance use disorder, require a thorough assessment to understand their implications on anesthesia response during both induction and emergence as well as their influence on postoperative recovery. Depression and anxiety before surgery correlate with decreased pain thresholds, leading to heightened postoperative pain levels and increased analgesic needs. Moreover, they serve as robust predictors of chronic postoperative pain and independently elevate the risk of postoperative delirium. Additionally, careful consideration of the medications employed to manage these conditions is essential due to potential interactions with anesthetic drugs, which can impact perioperative care and patient outcomes.

- FL disease can affect drug metabolism and anesthesia tolerance.

Kaley's current medication regimen includes several agents that have implications for anesthesia management. Caution should be exercised in patients taking lithium due to its narrow therapeutic index (0.6-1.2 mmol/L) with doses guided by plasma levels; concentrations above 1.5 mmol/L may induce intoxication. Renal function and volume status changes can affect plasma levels, especially with medications like diuretics and NSAIDs, necessitating pre- and postoperative monitoring. Lithium should be considered for discontinuation 48-72 hours before surgery in consultation with Kaley’s psychiatrist. Lithium prolongs neuromuscular blockade phases during anesthesia, necessitating appropriate monitoring for patients undergoing neuromuscular blockade. Amitriptyline (tricyclic antidepressant) presents an extensive side effect profile, including cardiac conduction changes and lowered seizure threshold, warranting caution during anesthesia and when combined with sympathomimetics or tramadol due to potential hypertensive crises and increased seizure risk. As a migraine medication, sumatriptan warrants attention for potential interactions with anesthesia and other drugs, particularly serotonergic agents.5 Coordination with pain management specialists is vital, given buprenorphine's unique properties and implications for perioperative pain control.2

Kaley is scheduled for instrumentation and fusion from T2 to L2 of her spine in the prone position under general anesthesia. This procedure entails specific considerations, such as tailoring anesthesia to accommodate her medical conditions and medication regimen ensuring safe induction, maintenance, and emergence from anesthesia. A good perioperative pain control plan, considering her opioid tolerance and chronic pain conditions, needs to be in place to optimize postoperative recovery and minimize complications.

Failure to assess and optimize these conditions preoperatively can lead to various anesthesia-related complications, including inadequate pain control, respiratory depression, airway obstruction, cardiovascular instability, drug interactions, and delayed recovery. A thorough understanding of Kaley's medical history and medication regimen is essential for developing an individualized perioperative plan, optimizing anesthesia safety, and ensuring successful surgical outcomes. Collaboration among the surgical team, anesthesia providers, pain specialists, and the psychiatric team is critical for comprehensive patient care.

LASRA (Carlos E. Restrepo-Garces, MD) Complex comorbid conditions, including a combination of obesity (We don’t know the BMI) plus scoliosis (There is no data for initial age and physiological and/or anatomical extent). in a patient with recreational substance use with neuropathic pain plus OSA, makes this a complex patient. There is a major risk for drug interactions in terms of central nervous system (CNS) depressant effects and serotoninergic side effects. The interactions of lithium, buprenorphine, and amitriptyline on the QT duration should be considered. Also, the need for a high-dependency unit or intensive care and the risk of respiratory support, despite the use of CPAP, increase her risk. In Colombia, not all the cities can have a comprehensive program for this population, not only from the human resources point of view but also from the logistical point of view.

AOSRA-PM (Sathish Rajaselvam Parameswaran, MD, and Jagannathan Balavenkatasubramanian, MD ) She weighs 105 kilograms and has a history of OSA. She must undergo a long-segment spine deformity correction in the prone position. This obviously would require GA, and the surgery is going to last a minimum of 4 to 5 hours. This proposition by itself is going to present us with a lot of challenges. Additionally, this patient is suffering from multiple psychiatric disorders and is on multiple medications, which can make management during the perioperative period difficult.

The airway might be challenging. Her respiratory compliance might have been compromised, with both obesity and spine deformity contributing to this, particularly because she has a high thoracic apex. We would like to know about her PaO2 and PaCO2 levels. PaCO2 levels are expected to be high. It would not be surprising if we saw her PaO2 levels on the lower side. This might have implications for her heart. We would like to look at her right and left heart through an echocardiogram (ECG), including commentary on her pulmonary pressures. It is possible that she has systemic hypertension secondary to her OSA.

OSA might have raised her hematocrit. The prone position she must assume for the 5 hours of surgery, combined with her body habitus and raised hematocrit, would predispose her to the development of deep vein thrombosis.

Interstitial pressures are going to rise higher in the prone position compared to her normal body weight counterparts. This surgery is expected to bleed a lot, both due to the number of segments involved and difficult anatomy. Maintaining perfusion pressures and tissue oxygenation throughout the surgery would be the primary concern during the intraoperative period, as this would lead to optimal outcomes in the postoperative period.

The patient also suffers from OUD, bipolar disorder, anxiety, migraines, and fibromyalgia, for which she is taking multiple medications. These might have implications for anesthetic and pain management in the postoperative period. Withholding certain drugs may precipitate her psychiatric symptoms, and the continuation of certain drugs can lead to significant drug interactions during anesthesia. There might be variations in the requirement for the depth of anesthesia compared to the normal population due to alterations in the levels of neurotransmitters in the brain. Most importantly, we might encounter significant difficulty in the management of pain. The presence of some of these conditions predisposes her to develop chronic post-surgical pain.

Amitriptyline acts by inhibiting the reuptake of noradrenaline and serotonin at synaptic clefts. It is associated with a few side effects, such as arrhythmias, urinary retention, dry mouth, sedation, and postural hypotension. These side effects are attributed to its actions on histaminic and cholinergic systems. They might induce an increased requirement for anesthetic agents in the intraoperative period due to the increased availability of neurotransmitters in the CNS. There is a chance for exaggerated hemodynamic responses to sympathetic stimulation and indirectly acting vasopressors. We would like to continue amitriptyline in the perioperative period since the risk of discontinuation syndrome in this patient can pose serious challenges in the overall management of her care when compared to the hemodynamic challenges and drug interactions we might encounter intraoperatively. Serotonin syndrome is a consideration, but with due diligence to avoid certain drugs, it can be prevented.

The patient is taking lithium for her bipolar disorder. Lithium is associated with a narrow therapeutic margin. Slight increases in plasma lithium levels can lead to profound clinical manifestations, such as arrhythmias, hypotension, sedation, and neuromuscular weakness. Such an alarming rise in lithium can happen in this patient due to the expected hemodynamic fluctuations, fluid shifts, and drug interactions. It would be a prudent decision to stop lithium 3 to 4 days before surgery. Lithium can be safely restarted in the postoperative period once the patient is fully oriented and hemodynamically stable after serum electrolytes have stabilized and after the patient tolerates oral feeds.

Sumatriptan is a serotonin agonist used in the management of migraine and other headaches with similar pathogenesis. We are unaware of any absolute contraindications for using sumatriptan in the perioperative period. This patient has been taking amitriptyline and sumatriptan for various reasons, which she has been tolerating quite well. But this combination might predispose her to some form of autonomic dysfunction, along the lines of serotonin syndrome, if an aggravating drug were to be used in the perioperative period.

Buprenorphine had been initiated because of her OUD. It is a partial agonist at the mu receptors with higher affinity, less intrinsic activity, a longer half-life, and a better safety profile. This pharmacological profile has allowed it to largely replace methadone in the treatment of opioid addiction. Concerns about the management of patients on buprenorphine in the perioperative period include inadequate pain control (if the patient had been using a larger dose) and withdrawal and relapse of opioid addiction (if buprenorphine had to be stopped and the patient must receive a large dose of full mu agonists). As a protocol in our institution, all our patients receive buprenorphine transdermal patches that release the drug at 10 micrograms per hour, starting on the day of the surgery. This helps us reduce the use of parenteral opioids in the postoperative period and might have a role to play in neuropathic pain. In this patient, we would like to continue buprenorphine into the perioperative period, albeit at a lower dose.

AFSRA (Francois Retief, MMed) This patient will require intervention by a multidisciplinary team before surgery, which should not be rushed. There are several aspects that need to be investigated and optimized:

- The combination of scoliosis, OSA, non-compliance with CPAP, and smoking of cannabis raise concerns regarding her pulmonary and cardiac (especially right heart) function. This should be evaluated and optimized.

- Her weight is a perioperative concern in terms of positioning for surgery, anesthetic drug kinetics, difficulty of surgery, bleeding, maintaining lung volume after surgery, etc.

- Her FL disease is not defined or quantified and may influence her drug metabolism and possibly other perioperative aspects like coagulation and metabolism.

- There may be a concern for drug interactions. For example, some combinations of her medication may lead to serotonin syndrome or prolonged QT interval, and the risk may increase with surgery and anesthetic medications. Additionally, cannabis and cessation thereof may influence buprenorphine levels.

- She is at very high risk for poor pain control postoperatively as well as for persistent and chronic pain, having several risk factors like anxiety disorder, opioid use, substance abuse, widespread pain, being a young female, and undergoing complex spine surgery. It is important to investigate and optimize her pain preoperatively, involving her pain physician. Her use of recreational drugs may be the consequence of poor pain control. If cannabis is helping her pain and not interfering with her bipolar disorder, it would be better as a prescribed part of her treatment. There are also better options for chronic migraines, like Botox injections or anti-calcitonin gene-related peptides.

- Evaluation and optimization by psychiatry and psychology are required. This may include consideration of newer modalities for bipolar disorder and anxiety, evaluation of recreational drug use and personality traits for addiction, and optimizing management of her OUD.

CAS (Ala Mahamid, MD, Elizabeth Woodford, MD, Paul Tumber, MD, and Hance Clarke, MD) In routine preoperative documentation, it is imperative to record significant medical conditions, including but not limited to diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, respiratory issues, obesity, or neurological disorders. Regarding Kaley’s presentation, her medical history includes:

- OSA - If Kaley is not compliant with CPAP, this necessitates vigilance regarding potential respiratory complications linked to anesthesia and patient positioning during the surgical procedure, given the possibility that ventilation may be challenging. Anticipated challenges may include difficulties with bag/mask ventilation and intubation, for which video laryngoscopy or awake fiberoptic intubation should be considered. Furthermore, a comprehensive evaluation of respiratory function is imperative, accounting for potential alterations in physiological dynamics, the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of administered anesthetics, and postoperative anxiolytics and analgesics. Given her OSA and increased BMI, Kaley may also be more sensitive to the respiratory depressant effects of opioids and sedatives. This issue will also necessitate a heightened level of respiratory monitoring for apnea episodes postoperatively.

- Scoliosis - The patient presents with scoliosis, which indicates her impending surgery. In this context, it is imperative to remain cognizant of the following considerations:

- Identification of compromised functions or diminished organ reserves that may predispose her to potential perioperative complications, necessitating maximal preoperative optimization.

- Patients with scoliosis may have restrictive lung disease, and this may place them at greater risk of developing postoperative pulmonary complications.

- Fibromyalgia - The management of perioperative pain in patients with fibromyalgia poses a significant challenge and necessitates an approach that addresses symptoms to mitigate heightened central sensitization and reduced descending inhibitory pathways for analgesia and inhibition, along with addressing associated psychological syndromes, such as anxiety, catastrophizing, and depression. The objective is to effectively diminish both acute and prolonged postoperative pain.6

- FL - Patients diagnosed with FL experience prolonged recovery from anesthesia, indicating a modification in drug metabolism that is not contingent upon metabolic risk factors.7

- Bipolar - Mood stabilizers are commonly prescribed for patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder includes Bipolar I, characterized by manic episodes, and Bipolar II, characterized by hypomanic and major depressive episodes. To manage mood swings, patients may receive monotherapy or a combination of medications.8 Since mood stabilizers can significantly impact anesthesia, it is recommended to discontinue lithium before surgery as it can be stopped abruptly without causing withdrawal symptoms. Given its half-life of 24–36 hours, lithium should be discontinued 72 hours prior to the surgical procedure.9

- Migraine - Kaley’s pre-existing history of a migraine disorder and the fact that she is a young woman increase her risk of having significant acute pain10 and the likelihood that she will develop persistent opioid use and chronic post-surgical pain following her surgical intervention.8,11

- Anxiety --Likewise, the surgeons and/or a transitional pain service (TPS) should offer Kaley a preoperative education session to help her understand what her perioperative course will entail and alleviate some of her anxieties. Pain Canada has recently created a course for people undergoing surgery that educates them about the potential pain experienced before and after surgery (https://www.paincanada.ca/course/managing).

- Kaley’s current medications:

- Amitriptyline - This is an older medication used for chronic pain, and caution should be taken when using it in patients with preexisting arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities. A routine preoperative electrocardiogram (EKG) should be performed in patients identified as potentially high-risk. There are reports of serotonin syndrome with other opioids, tramadol, and other second-generation antipsychotics. Still, there is no reason to discontinue or adjust before surgery unless there are already anticholinergic side effects being experienced, such as excessive sedation, dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, palpitations, or urinary retention. In this case, a rotation to a tricyclic antidepressant with fewer anticholinergic side effects, such as nortriptyline, may be helpful.

- Lithium - This medication can extend the duration of neuromuscular blockade, potentially leading to reduced anesthetic requirements. Some literature advises withholding its administration for 72 hours preceding the surgical procedure. 8 However, this is also up to the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist.

- Sumatriptan - Serotonin 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists, utilized in the initial management of migraines, can be administered preoperatively, especially if the drug is being used to prevent migraine and the patient does not have any contraindications to its use nor any side effects. This could be held without a migraine on the day of the surgical procedure.12

- Sublingual buprenorphine - There have been several guidance documents regarding the management of suboxone (sublingual buprenorphine) in the perioperative period.13-15 In Kaley’s case, there

seems to be time to optimize the dose of buprenorphine/naloxone before surgery. To make a sufficient number of mu-opioid receptors available to Kaley, we would favor a taper of her sublingual buprenorphine dose following an informed

discussion with her outpatient provider. With Kaley’s consent, we will taper her sublingual buprenorphine to 10-16 mg if she tolerates this wean for her to have the maximal benefit of mu opioids, which will undoubtedly be

required. A dose of 8-16 mg maximum provides the analgesic sweet spot needed to afford the mu opioids’ ability to work in the postoperative setting.15 In the absence of sufficient time to wean Kaley, I would direct

the reader to a Canadian Delphi on the perioperative management of buprenorphine/naloxone,14 which walks the anesthesiologist through how to handle high-dose buprenorphine administered on the morning of surgery.

- Recreational cannabis is very topical in Canada. Two guidelines have been published recently, one by our group in Canada16 and the other by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine.17 Both guidance documents stress the importance of asking patients about their perioperative cannabis use. First, we must understand if patients’ cannabis use is daily and medically authorized or is more recreational. This will inform our decision as to whether to ask the patient to refrain prior to the operating room. Furthermore, the type of cannabinoid product being used (ie, THC to CBD ratio) and routes of administration (Although Kaley smokes, this may not be the only route by which she is consuming cannabis) should be considered. Based on the answers to the above questions, the anesthesiologist can determine whether to counsel patients to refrain from their routine use on the day of surgery. Patients may be cross-tolerant and require a higher dose than anticipated to induce general anesthesia, and thus, the induction agent is titrated to loss of consciousness. Some have suggested the use of BIS/entropy to guide anesthetic requirements.

Note: It is important to understand the purpose of a patient’s buprenorphine therapy (ie, high dose opioid use in pain management with concomitant OUD versus OUD treatment without pain), the risk of relapse, and the anticipated level of postoperative pain with a focus on patient-centered care. Potential drug-drug interactions resulting in QT-interval prolongation, serotonin syndrome, paralytic ileus, diminished analgesic efficacy, or exacerbation of withdrawal symptoms should be acknowledged if one chooses to discontinue buprenorphine preoperatively. Stopping buprenorphine preoperatively has fallen out of favor.

The ASRA guidelines recommend that frequent cannabis users be counseled on the potentially negative effects on postoperative pain control if they consume and are in a potential withdrawal state. At the same time, the patient must understand that they would be at risk of being canceled if they show up acutely intoxicated.17 Data further supports that patients consuming cannabis are at higher risk for a myocardial infarction under general anesthesia.18 A discussion about other concurrent drug use would be wise in this context, and counseling in those domains is essential. Note, there is no rationale for or needing to urine screen a patient now.

- What preoperative tests would you like to perform?

ASRA Given her history of FL disease, it would be valuable to obtain liver function tests. Ketamine undergoes hepatic metabolism by the cytochrome p450 system and has been associated with elevation of liver enzymes.19,20

Ketamine can be used as a part of multimodal analgesia, and thus, knowledge of her baseline liver function would be useful to determine whether ketamine can be safely utilized as an adjuvant in her care.

ESRA A thorough preoperative assessment, including baseline laboratory tests (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation studies, and liver function tests) to assess her overall health status, liver function, coagulation profile, renal function tests, EKG, sleep study for the presence of obstructive sleep apnea, drug screening, imaging studies (spine MRI, x-ray, and pulmonary functional tests to review scoliosis impact over the respiratory function), psychiatric assessment, and specialized consults (psychiatric evaluation, hepatology consultation, ECG, and/or cardiac consult), is essential for Kaley's safety during her planned spinal surgery under general anesthesia, ensuring proper risk mitigation and optimal perioperative care.

Overall, a comprehensive preoperative assessment tailored to Kaley's specific medical history and surgical procedure is essential to identify and mitigate potential risks, optimize perioperative care, and ensure the best possible outcomes.

LASRA There is no data regarding her functional capacity (METs, etc.); therefore, basal ECG and pulmonary function tests are of major value. I would also order a complete blood count, liver enzymes, and coagulation tests.

AOSRA-PM Routine investigations, such as a complete hemogram and renal function test, including electrolytes, chest radiograph, and EKG, will be obtained. Pulmonary function testing, echocardiography, and arterial blood gas analysis would be required in this patient. Pulmonary function testing would help us stratify the risk for post-operative pulmonary complications. Echocardiography would give us information about the strain on the right heart as well as about left ventricular hypertrophy, if present. Polysomnography would help us quantify her OSA. However, since she had already been prescribed CPAP and it is not going to alter our management, we would refrain from ordering polysomnography.

AFSRA Routine tests in this scenario would be full blood count, electrolyte, urea, creatinine, liver functions, coagulation studies, lithium levels, type and screen for blood transfusion, ECG, and imaging of the spine and chest. Other tests that may be indicated after history and examination are lung function testing, urine toxicology screen, transthoracic echocardiography, and sleep studies (if not already done).

CAS For a spine surgery patient undergoing preoperative evaluation, the following diagnostic assessments are typically conducted:9

- Hematological Tests:

- Complete Blood Count: Evaluates for anemia, infection, and overall blood cell counts.

- Coagulation Profile: Determines the patient's clotting ability.

- Blood Chemistry: Assesses electrolytes, creatinine, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), glucose, and HbA1C.

- Blood Type and Rh Factor: This test identifies blood type for potential transfusion requirements and facilitates preparation for transfusion or blood conservation strategies, such as autotransfusion.

- ECG - Analyzes the heart's electrical activity and assesses cardiac health. In this case, given the medications involved, an ECG would be reasonable.

- Chest X-ray - This provides a baseline assessment of lung and cardiac health, detecting any preexisting lung conditions or abnormalities. Given the ongoing smoking history, this also would be reasonable.

- Our presumption is that the surgical team has conducted the necessary spine imaging (eg, x-rays/ MRIs), and the surgical plan has been determined based on these findings and Kaley’s symptoms. Given her age, further investigations, such as pulmonary function tests and ECG, are not necessary unless a specific issue is identified from the patient's medical history, CXR, or local surgeon's preferences. It's essential to recognize that specific tests may vary based on individual patient needs and the planned surgical procedure.

Part 2: Analgesic Management and Patient Counseling

- What is your plan regarding pain management (please consider pharmacological +/- regional anesthesia means) for her in the:

- Pre-operative/pre-emptive

- Pre-operative/pre-emptive

ASRA It is important to thoroughly discuss the perioperative plan with the patient so she is properly educated on the multiple modalities that may be used

in her care. It is also important to collaborate closely with the surgical team and the patient’s outpatient buprenorphine prescriber. The home dose of buprenorphine should be verified, as well as the time of the last dose taken. It

is important to plan to continue her buprenorphine21 as studies suggest that patients are at risk of relapse when buprenorphine is discontinued.22 While there is growing consensus to continue buprenorphine, controversy

continues to exist as to the proper dosing of buprenorphine in the perioperative period. I would recommend consulting with regional pain medicine specialists about any regional techniques that may offer benefits.

ASRA It is important to thoroughly discuss the perioperative plan with the patient so she is properly educated on the multiple modalities that may be used

in her care. It is also important to collaborate closely with the surgical team and the patient’s outpatient buprenorphine prescriber. The home dose of buprenorphine should be verified, as well as the time of the last dose taken. It

is important to plan to continue her buprenorphine21 as studies suggest that patients are at risk of relapse when buprenorphine is discontinued.22 While there is growing consensus to continue buprenorphine, controversy

continues to exist as to the proper dosing of buprenorphine in the perioperative period. I would recommend consulting with regional pain medicine specialists about any regional techniques that may offer benefits.

ESRA For Kaley's pre-operative/pre-emptive pain management, considering her complex medical history and the planned spinal surgery, the following plan is proposed:

- Patient education and counseling about managing postoperative pain expectations and the importance of pre-emptive strategies.

- Discuss the anticipated pain management plan, including pharmacological and regional anesthesia interventions, potential side effects, and expected benefits.

- Continue her current pain medications, including sublingual buprenorphine for opioid maintenance therapy, ensuring consistent pain control while minimizing the risk of withdrawal.

- Utilize a multimodal analgesic approach to minimize opioid use and reduce the risk of opioid-related complications.

- Explore the potential for regional anesthesia techniques (eg, epidural or peripheral nerve blocks) to provide targeted pain relief and reduce the need for systemic opioids.

LASRA Multimodal analgesia (MMA) should be the answer at any point. Pre-op: paracetamol and COX2 inhibitors/NSAIDs in concordance with an open dialogue with the surgeon regarding the team’s preferences in terms of bone healing and COX2 agents. However, any non-opioid strategy should be considered, including gabapentinoids (even with the decrease in terms of evidence for routine pre-op use).

AOSRA-PM The patient would receive these medications the night before and the morning of surgery: paracetamol 1g per oral, aceclofenac 100 mg per oral, pregabalin 150 mg per oral, and her routine sublingual buprenorphine 8 mg.

AFSRA Chronic pain and other comorbidities should be well optimized preoperatively on a prescribed regimen as above. We would initiate pregabalin and titrate to optimal effect over 1 or 2 weeks if there is a neuropathic component to her pain. Buprenorphine or methadone dosing would be optimized by a psychiatrist in our setting.

CAS Before proceeding with surgery, our team’s goal would be to have a discussion regarding the perioperative journey immediately post-surgery and to set plausible expectations. Pain control will be a challenge, but the acute pain team will do their best to help her through the immediate postoperative course, and ultimately, a TPS can be utilized to facilitate discharge and liaise with her outpatient opioid agonist therapy (OAT) prescriber. It is essential to evaluate several factors regarding her OAT for her opioid use disorder, psychological distress, and other patient-specific attributes correlated with sustained opioid usage post-surgery. Risk factors associated with increased postoperative pain following spine surgery encompass heightened levels of anxiety, depression, pain catastrophizing, pain sensitivity, fibromyalgia, preoperative opioid utilization, and female gender.23 If these risk factors are identified, counseling and brief interventions (ie clinical hypnosis, ACT-based therapies) have shown promise with respect to reducing opioid consumption and pain catastrophizing following oncologic surgeries.24

As stated earlier, a reduction in the patient’s sublingual buprenorphine dose to 10-16 mg as tolerated would be ideal. She would continue this dose perioperatively and be discharged as close to her previous dose if possible. An overall discussion regarding preoperative and intraoperative interventions that have demonstrated efficacy in mitigating postoperative pain includes the administration of acetaminophen, COX-2 specific inhibitors, or NSAIDs, intravenous ketamine and lidocaine infusions, and regional analgesic techniques, depending on the center’s preferences with respect to neuraxial surgery.14 Although there is limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of local wound infiltration, intrathecal and epidural opioids, erector spinae plane block, thoracolumbar interfacial plane block, intravenous lidocaine, dexmedetomidine, and gabapentin are all potential tools that can be discussed with the patient regarding the postoperative course and medications that will help reduce pain and opioid consumption.25

- Intra-operative

ASRA MMA should be utilized in the intraoperative period. Buprenorphine is known to bind tightly to the opioid receptor and, thus, at high doses, may preclude the binding of full mu agonists. Full mu agonists may still be utilized; however, medications that also have high binding efficiency are recommended. such as sufentanil or hydromorphone. Sufentanil, in particular, has high binding efficiency and has been reported to produce a maximal effect with 50% of receptor occupancy; thus, modest doses may provide effective analgesia in patients on buprenorphine.26 Lidocaine and ketamine infusions are also recommended.21,27 Other potential adjuvants may include dexmedetomidine or magnesium and intravenous acetaminophen.

ESRA For Kaley's pain management during and after surgery:

Use a balanced approach, incorporating paracetamol 1g Q6h (to keep after surgery as basic regimen), NSAIDs (p.e., parecoxib 40mg Q12h IV to keep after surgery as basic regimen for 3 days), ketamine (start at 0.2 mg/kg/h and adjust to EEG/analgesia monitoring), and dexamethasone (4-8 mg single dose) to reduce opioid use and minimize pain. Consider regional anesthesia methods, such as epidural (postoperative epidural catheter placement by the surgeon) or erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks (single shot or continuous block performed by the anesthesiologist before surgery, discussed with the surgical team), for targeted pain relief during surgery.25 Other suggestions for intra-operative analgesia are magnesium sulfate (50 mg/kg not exceeding 2g/10mL, slow injection, single dose), metamizole 2g/100 ml infusion (a drug not approved in the USA, but available in many European countries), tramadol 100 mg Q12h, and finally morphine 20 minutes before emergence 5-8 mg IV.

Nociception monitors can also be used for this patient to help guide the pain management intra-operatively. The four most commonly available monitors on the market include

- Analgesia Nociception Index (ANI from Mdoloris Medical System)

- Surgical Pleth Index (SPI from GE Healthcare)

- Pupillometry (AlgiScan/Neurolight from IDMed), and

- Nociception Level Index (NOL from Medasense). The first two monitors assess autonomic activity, the third one focuses on parasympathetic activity, and the fourth is a multiparametric monitor. Literature suggests that these indexes offer greater precision in detecting intraoperative nociception during general anesthesia. Moreover, simultaneous intraoperative use of nociception monitors (NOL index) alongside EEG monitors (BIS index) has been shown to expedite emergence from anesthesia and post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) recovery. Additionally, they help in determining the adequacy of regional techniques in providing antinociception during major surgery. These monitors also contribute to lower postoperative pain scores and reduced opioid consumption in the hours following surgery.28

LASRA A ketamine infusion should be offered in patients with previous opioid use, severe postoperative pain, or risk of chronic pain. IV paracetamol can also be given as an adjuvant. If there is a chance of postoperative mechanical ventilation, dexmedetomidine can also be taken into account. In Latin American countries, Metamizol is a part of the non-opioid strategy. It is banned for human use in the United States, Canada, and some European countries, but in terms of guidelines, it is part of the Nederland Guide of acute pain relief.

AOSRA-PM

- Intravenous paracetamol 1 g Q6H

- Intravenous Ketorolac 30 mg Q8H

- Intravenous Fentanyl 2 mics per kg at induction and repeated at 1 mic per kilogram every 60 to 90 minutes

- Intravenous fentanyl 0.5 mics per kilogram for rescue

- Infusion of dexmedetomidine at 0.3 to 0.6 mics per kilogram per hour

- Intravenous magnesium at the start at 50 mg per kg, for a maximum of 2 grams

- Four quadrant erector spinae plane block before incision with ropivacaine 0.2% at 3mg per kg divided and distributed across the four quadrants

AFSRA Acetaminophen (usually IV), dexamethasone, and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, as well as boluses and infusions of lidocaine, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium, would be used. A short-acting opioid infusion like remifentanil would be titrated intra-operatively as required. Bilateral ESP catheters would be placed with initial injections at more than one level if used intraoperatively. This blocks most of the pain generators in spine surgery reliably via the dorsal rami, and there is also slow diffusion to the nerve roots and sensitive dorsal root ganglia, blocking the nociceptive supply to the vertebral bodies.

CAS During the intraoperative phase of the planned spinal fusion, pain management strategies can entail utilizing pharmacological interventions and regional anesthesia techniques to achieve superior pain relief. A typical general anesthesia regimen with an opioid-based induction and remifentanil infusion up to 0.1 micrograms/kg/minute has become commonplace at many institutions; other multimodal infusions could include intraoperative ketamine and or lidocaine infusions. For ketamine, an example could be an initial bolus of 0.5 mg/kg along with a low dose of midazolam to decrease the risk of psychomimetic side effects. The initial bolus of ketamine can be followed by an infusion rate of 0.05 to 0.25 mg/kg/hr, with cessation of the infusion recommended 45 minutes before the conclusion of surgery to facilitate emergence from anesthesia. Ketamine is particularly beneficial for patients undergoing major or complex surgeries and those with a history of chronic pain, neuropathic pain, or opioid tolerance. It exerts an opioid-sparing effect of approximately 40% during the postoperative period, and hallucinations are rarely reported at these doses. For lidocaine, an initial bolus of 100 mg at induction followed by an infusion rate of 1-2 mg/kg/hr may be considered in conjunction with the ketamine or alone. Dexmedetomidine has also been found to be a helpful analgesic adjunct for patients with opioid tolerance or complex chronic pain, especially if the patient is not hypotensive, and intraoperative doses of 0.2-0.3 mcg/kg/hr are commonly used at our institution.

Prior to extubation, it would be ideal to administer a loading dose of a potent opioid, such as hydromorphone, and titrate it according to the patient's respiratory rate and vital signs. In the immediate postoperative phase, if further analgesia is required in the PACU in addition to supplemental doses of ketamine, it may be useful to consider an even more potent opioid, such as sufentanil.

From a regional anesthesia perspective, the surgeon can discuss a spinal/ epidural placement at the end of the case but will often not offer it. However, alternative strategies can be considered with the surgical team, such as placing a paravertebral or ESP block bilaterally for intraoperative pain management or potentially placing it near the end of the surgery if agreeable.

- And the post-operative period?

ASRA It is recommended to continue the patient’s home dose of buprenorphine and monitor the patient closely for uncontrolled pain. If her pain is not adequately controlled, several options exist, including potentially increasing her current dose of buprenorphine; however, this plan may be a more viable option in patients who are on less than 24 mg of buprenorphine daily. Lidocaine and ketamine infusions can be continued until maximum benefit is reached (usually not beyond 2 days for lidocaine infusions). Medications such as duloxetine can be beneficial; however, the patient, in this case, is already on amitriptyline and sumatriptan, and thus, the addition of another medication that prevents the reuptake of serotonin must be used with caution.

Non-pharmacologic modalities, such as music therapy, massage, mindfulness, relaxation techniques, and cognitive behavioral therapy, can also be used.

ESRA Overall, the goal is to ease Kaley's pain, minimize opioid risks, and help her recover well after surgery. Adjustments will be made as needed based on her progress and feedback. Regularly assess Kaley's pain levels and medication response, watch for side effects, such as sedation or respiratory depression, and adjust treatment accordingly, working closely with the healthcare team to ensure the best pain management plan tailored to her needs.

- Combine opioid and non-opioid medications to reduce pain and side effects.29

- Continue Kaley's usual pain meds (SL buprenorphine), adjusting doses as needed.

- Give scheduled acetaminophen and NSAIDs to reduce reliance on opioids.

- Offer patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) or epidural if needed for targeted relief.

- Use additional meds like gabapentinoids or tramadol for neuropathic pain.

- Encourage early ambulation and physical therapy for faster recovery.

LASRA Continuous epidural analgesia with a catheter inserted by the surgeon under direct vision is part of MMA, reducing opioids and facilitating the weaning of mechanical ventilation. If no neuraxial or regional techniques were used, lidocaine could also be part of this approach. In cases with expected opioid PCA use, a ketamine-opioid mixture should be an alternative. All non-opioids should be given scheduled, including gabapentinoids, if they have been used pre-op.

AOSRA-PM

- Intravenous paracetamol 1 g Q6H

- Intravenous Ketorolac 30 mg Q8H

- Intravenous fentanyl infusion at 0.5 to 1 mics per kilogram per hour

- Intravenous fentanyl 0.5 mics per kilogram for rescue

- Pregabalin 150 mg po bd

- Sublingual buprenorphine 8 mg bd

AFSRA We would plan for a longer-than-usual high-care admission. Preoperative analgesics, including pregabalin and buprenorphine or methadone, would be continued. MMA in the form of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, infusion of lidocaine, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium, and/or continuous ESP blocks using a bolus technique or high-volume infusion would be continued for the first 24 to 48 hours or longer.

CAS The postoperative phase presents challenges, particularly in complex surgeries and in patients with OUD. Adequate management of postoperative care is crucial to prevent the development of chronic postsurgical pain, which is influenced by various preexisting risk factors, as previously discussed. Postoperative pain management strategies encompass both opioid and non-opioid approaches, incorporating pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

A thorough discussion, as noted preoperatively, about the postoperative course must be had with Kaley to discuss her desires regarding both pain control and opioid analgesic use, given her history of an OUD. If analgesia is inadequate in the early postoperative period, we recommend6 the initiation/continuation of adjunct analgesia (NSAIDs, acetaminophen, gabapentin/pregabalin, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, or lidocaine). Also, assessing the effectiveness of the IV PCA (hydromorphone, fentanyl), which may require a higher dose given the dose that Kaley landed on based on her preoperative wean (ie, 10-16 mg), no dose adjustments would likely be needed if her dose is 8-10 mg. If all the above fails, we would support the reduction (not stopping abruptly) of the dose by half for 1 or 2 days to ensure that the mu opioids have an opportunity to act with more available receptors. Stopping altogether could set up an opportunity to have a fatal respiratory depressant effect. We would advocate for the patient being cared for in a step-down/ monitored setting if significant changes are being made in the POD 1/2 timeframe, as suggested above.14 Spine surgeons may allow a brief 24-hour course of an NSAID, such as intravenous ketorolac if the pain is not well controlled by other means and there is no issue with bleeding or hepatorenal dysfunction. Depending on the surgery, spine surgeons may wish to avoid NSAIDs due to individualized concerns over bony fusion healing.

- Would you consider switching to methadone prior to surgery? Why or why not?

ASRA No, there is no evidence to suggest that switching to methadone in the perioperative period would result in better outcomes. The patient is already

being treated successfully with buprenorphine for her OUD; thus, I would continue this management perioperatively.

ASRA No, there is no evidence to suggest that switching to methadone in the perioperative period would result in better outcomes. The patient is already

being treated successfully with buprenorphine for her OUD; thus, I would continue this management perioperatively.

ESRA The decision to switch Kaley to methadone prior to surgery should be meticulously evaluated, considering various factors. While methadone may offer advantages in pain management due to its extended duration of action and potential NMDA receptor antagonist properties, its pharmacokinetic profile, including a long half-life and potential for drug interactions, necessitates careful consideration to avoid adverse effects.30 Kaley's complex medical history, including psychiatric disorders and polypharmacy, further emphasizes the need for cautious evaluation to ensure compatibility with methadone therapy and minimize adverse events.

There is recent evidence30 suggesting reduced cocaine use, cravings, anxiety, and cardiac dysfunction among those receiving buprenorphine compared to methadone, while methadone showed reduced hospitalization and alcohol use. However, methadone demonstrates better treatment retention than sublingual buprenorphine. Notably, methadone's full agonist activity at mu opioid receptors and potential for QT interval prolongation necessitate cautious use, particularly when combined with medications prolonging QT interval (like amitriptyline) or causing electrolyte disorders. Conversely, buprenorphine's partial agonist activity and lower risk of QT prolongation make it a viable alternative. Collaborative decision-making, involving a pain specialist and considering these factors and evidence, is essential to optimize Kaley's perioperative pain management and overall well-being.

LASRA Methadone seems attractive because it is an antagonist of the NDMA, but there is a risk of QT prolongation when lithium is used. In Colombia, only oral methadone is available; no IV or syrup forms are available. The situation is the same for most South American countries.

AOSRA-PM The patient was already on sublingual buprenorphine. We wouldn’t switch to methadone. We don’t have any experience with methadone. Logically, too, methadone wouldn’t be preferred as it is associated with side effects, such as delirium, prostration, and blurred vision. It is associated with arrhythmias, such as torsades de pointes. It is also known to prolong the QT interval. The patient is already on lithium, which has a narrow therapeutic window, and considering its propensity to cause cardiotoxicity, it would be a prudent decision to avoid methadone in this patient.

AFSRA Both approaches are acceptable. We would probably switch to methadone in this case. The risk for poorly controlled postoperative pain is high, and buprenorphine will likely not be useful as an analgesic, being a partial agonist on the background of tolerance and hyperalgesia. She is already on a dose near the ceiling effect, which implies high mu receptor occupancy and limited availability for the action of added full agonists. The addition of other opioids may also hold a high risk for relapse in this patient. Methadone, as a full mu agonist lacking the psychomimetic effects of other opioids and having NMDA-blocking and SNRI activity, may limit the requirement for additional opioids and minimize the risk of cravings and relapse. A psychological evaluation may help determine whether she has personality traits for addiction, which would support the decision. If her sleep apnea is not well controlled, buprenorphine may be the safer option.

CAS In patients with OUD, there exists a continual discourse surrounding the administration of buprenorphine/naloxone, in particular, its potential to block opioid analgesics when exceeding 16 mg daily.15 Our recommendation advocates for the continuation of buprenorphine at a sublingual dosage of 8-16 mg on the day of surgery supplemented by short-acting full mu agonists for postoperative pain management over a period of 2-4 days as needed, acknowledging the possibility of necessitating an extended duration beyond initial projections.21 Some divergent viewpoints pertain to doses exceeding 8 mg per 24 hours but not surpassing 12 mg, wherein the guidance supports the uninterrupted administration of buprenorphine throughout the perioperative phase. For individuals receiving doses beyond this range, a tapering regimen to achieve a maximum dose of 8-16 mg would be ideal if possible.

There are two main reasons why we would strongly advocate against the practice of switching a patient from buprenorphine to methadone prior to surgery:

- Given buprenorphine’s partial agonism at the mu-opioid receptor, converting to methadone will be quite challenging for the patient, who is currently stable after a lifelong battle with addiction. Provincial data in Ontario during the opioid crisis continues to report that very few fatal opioid overdose cases are found with buprenorphine in their blood supply. Protection against respiratory depression, which would also be useful in the context of postoperative care, and the addition of supplemental opioids, such as fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone, would be lost. Methadone titration for chronic pain control necessitates a normal gap of 3 days between dose adjustments based on its long half-life and pharmacologic profile. This makes initiation of methadone for pain control a major challenge in the setting of acute or chronic pain, where there is an expected reduction in acute pain over time countered by an increase in pain with mobilization, especially after spine surgery.

- From a humanitarian perspective, besides problematic pain management, which is paramount to the anesthesiologist, discontinuation of buprenorphine-naloxone may hinder harm reduction with respect to addiction and increase the possibility of relapse and subsequent inadvertent overdose (especially if needing to combine methadone and a full mu-opioid agonist is realized). Some expert opinions suggest improved treatment retention and lower misuse rates with discontinuation but do not acknowledge the greater risk of destabilizing a patient who has conquered a lifelong battle with OUD when opioid replacement therapy is stopped. According to the reviewed literature, there is no evidence to suggest that discontinuation of buprenorphine is the preferred method of OUD relapse prevention. If patient well-being beyond the operative room is to be factored into the decision-making process, current practice advisories and guidelines are insufficient at the moment, so we would not support a switch to methadone from buprenorphine-naloxone at our institution.

- What preoperative information would you provide for her in terms of optimizing her pain control postoperatively?

ASRA It is vitally important to educate the patient about her perioperative analgesic plan. It would be essential to inform her that there are multiple

methods to control her pain postoperatively. I would let the patient know that we will continue her buprenorphine and, in addition, use adjuvant medications to ensure her pain is adequately controlled. I would also recommend involving her

family or a support person.

ASRA It is vitally important to educate the patient about her perioperative analgesic plan. It would be essential to inform her that there are multiple

methods to control her pain postoperatively. I would let the patient know that we will continue her buprenorphine and, in addition, use adjuvant medications to ensure her pain is adequately controlled. I would also recommend involving her

family or a support person.

ESRA To optimize Kaley's pain control postoperatively, the following information should be provided:

- Discuss realistic expectations for pain control postoperatively, emphasizing that while complete pain relief may not always be achievable, the goal is to minimize pain to a tolerable level that allows for functional recovery. Discuss the importance of adjuvant pain management strategies, such as relaxation techniques, deep breathing exercises, and early mobilization, in enhancing pain control and promoting recovery.31

- Inform Kaley about the importance of regular pain assessment by healthcare providers using a standardized pain scale to monitor her pain levels and adjust treatment as needed. Educate Kaley about the concept of multimodal pain management, emphasizing the use of a combination of medications and techniques to address pain from different angles and reduce reliance on opioids.32

- Review Kaley's current medication regimen, including her baseline pain medications, such as sublingual buprenorphine, bipolar disorder medication lithium and amitriptyline, and migraine prescription of sumatriptan. Review how these medications will be continued or adjusted postoperatively to optimize pain control. Discuss the addition of other pain medications intra- and postoperatively, such as strong opioids (fentanyl/remifentanil) and NMDA inhibitors (ie, ketamine and magnesium sulfate) and acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, or tramadol, to complement her existing regimen and enhance pain relief as well as potential side effects of pain medications, such as sedation, constipation, nausea, or itching, and strategies to manage them effectively.

- Provide information about any regional anesthesia techniques used during surgery, such as epidural analgesia (EPA) or fascial plane blocks (single shot or continuous), and how they will contribute to pain control in the immediate postoperative period. 25 IV PCA with opioids would be considered the last resource as it could potentiate opioid addiction.

- Finally, outline the plan for postoperative follow-up appointments with healthcare providers to assess Kaley's pain control, monitor for any complications, and make any necessary adjustments to her pain management plan.

LASRA Patient education is of paramount importance and can be a part of the anesthesia and pain clinic team. Information regarding pharmacological and non-pharmacological options and psychological support for the pain journey during recovery can be given.

AOSRA-PM The surgery by itself is going to involve a large incision extending from the thorax to the lumbar region. It will involve significant tissue destruction and good amounts of instrumentation and de-rotation. We would have to expect significant pain in the postoperative period. This, combined with a history of opioid use disorder and use of multiple drugs preoperatively (for various indications), is going to make analgesia management challenging. Her history of OSA would have rendered the patient super sensitive to opioids. Opioid use is also going to be tricky in this particular patient. We would use MMA, which might require re-evaluation and re-titration in the postoperative period.

AFSRA The patient should play an active role in her pain management and work with the team. An agreement should be reached regarding open communication and disclosure, and patient fears about possible undertreatment of pain should be addressed with a plan for aggressive pain management. We would discuss the challenges, realistic expectations, and goals for her perioperative pain management, as well as the risk of relapse with the use of opioids during a stressful and painful event. The plan for the management of anxiety, cravings, and other symptoms should be agreed on. Discharge regimens and follow-up, as well as rehabilitation and social support systems, should be discussed. The patient’s family should be closely involved in the discussions.

CAS As discussed earlier, before proceeding with surgery, our team’s goal would be to have a comprehensive discussion regarding the perioperative journey and expected immediate post-surgical pain to set realistic expectations given Kaley’s medical complexities. Pain control may be a struggle given her buprenorphine/naloxone, but the acute pain team will do its best to help her through the immediate postoperative course, and ultimately, a TPS can be utilized to facilitate discharge and liaise with her outpatient OAT prescriber. We would ensure the gap between discharge and the connection with the outpatient care team is coordinated with respect to Kaley’s medications and discharge disposition.

Part 3: Regional Anesthesia Options

- Is neuraxial block an option in this case? If so, how would you go about it?

ASRA I would discuss this option with my regional colleagues.

ASRA I would discuss this option with my regional colleagues.

ESRA In Kaley's case, EPA stands out as a robust option for perioperative pain management, offering the potential to significantly reduce pain scores and opioid use. Prior to proceeding with this approach, it's crucial to thoroughly discuss with Kaley the risks, benefits, and potential complications of the neuraxial block, ensuring she comprehends the procedure and has the chance to address any queries before providing informed consent. The epidural catheter can be placed either under direct vision by the surgeon or with the assistance of ultrasound/fluoroscopic guidance towards the conclusion of the surgery.25 Following emergence and a neurological examination, the epidural infusion containing local anesthetic with or without opioids can be initiated. Additionally, implementing a standardized postoperative MMA regimen is imperative to further optimize pain management outcomes. Disadvantages of EPA include risks of complications, such as epidural hematoma and abscess, technical challenges in placement and post-operative pain management, hemodynamic effects like hypotension, motor blockade, delayed onset of action, catheter-related issues, limited mobility, urinary retention, potential patient discomfort, and increased healthcare resource utilization.

LASRA Spinal and epidural techniques are part of the analgesia strategy in this major spinal surgery. These are widely used in Latin America, especially a single dose of intrathecal morphine administered by the surgeon at the end of the procedure. Respiratory monitoring is mandatory in a high-dependency unit or in a step-down surgical unit in addition to the patient’s indication for CPAP use. Continuous epidural analgesia, again under the direct vision of the surgeon, provides an opioid-sparing approach. A low concentration of local anesthetics is advisable to detect early motor changes during the neurological evaluation of the patient.

AOSRA-PM Intrathecal opioids, caudal local anesthetics, and post-surgical bilevel epidural catheters with local anesthetics have been tried in major spine deformity corrections with varying results. We have moved away from using neuraxial techniques for pain management in our center. Intrathecal opioids have limited titratability, can cause delayed respiratory depression, are associated with nausea, vomiting, pruritis, and urinary retention, and the scope of analgesia doesn’t extend beyond 24 hours. Caudal and epidural local anesthetics can interfere with intraoperative motor-evoked potential monitoring, which is crucial for these kinds of surgeries. Post-surgical bilevel epidural catheters can prove ineffective because of unpredictable spread due to altered tissue planes after surgery. We wouldn’t consider neuraxial techniques as an option for analgesia in this patient.

AFSRA Epidural catheters, usually placed by the surgeon in our setting, are an option for postoperative analgesia. A disadvantage is that they may interfere with mobilization and neurological evaluation. For intraoperative analgesia, we would not use neuraxial techniques in this case since neuromonitoring will likely be used during surgery, or neurological evaluation will be required immediately after surgery. We would usually not use intrathecal morphine in this kind of patient due to the complexity of her OUD.

CAS Neuraxial block, such as spinal or epidural anesthesia, can be a viable option for certain spine surgeries. However, the decision to use a neuraxial block depends on various factors, including the specific procedure, the patient's medical history, and the preferences of the surgeon and anesthesia team members. Given her degree of scoliosis, the extensive anatomical area of interest, and the wide surgical field, performing or maintaining a neuraxial block for intraoperative anesthesia or analgesia may be technically challenging. Therefore, in her specific case, we would not recommend a neuraxial approach for intraoperative anesthesia or pain management. However, it is feasible to coordinate with the surgical team to insert an epidural catheter into the epidural space toward the end of the surgery in a sterile manner for postoperative pain management, especially in cases such as cancer-related pain where a more aggressive approach may be acceptable. Major issues with epidural management postoperatively in spine surgery include epidural hematoma and infection risk, hypotension, and difficulty in sorting out new onset of numbness and weakness postoperatively if using local anesthesia through the epidural catheter.

- Besides neuraxial blocks, is there a role for erector spinae blocks (ESPs) performed by surgeons in complex spine surgery?

ASRA I would discuss this option with my regional colleagues.

ESRA In complex spine surgery, ESPs offer distinct advantages. These blocks provide precise targeting of the nerves relevant to the surgical site, ensuring effective analgesia.33 By administering ESP blocks preemptively before surgery, they mitigate pain before surgical manipulation distorts anatomy, reducing reliance on intraoperative and postoperative opioids. Furthermore, should surgery extend beyond expected durations, the block can be conveniently repeated at its conclusion. In cases where postoperative pain is expected to persist beyond 24 hours, the placement of bilateral ESP catheters for continuous peripheral nerve block can significantly enhance postoperative pain control.

LASRA ESP can decrease VAS pain scores on the first postoperative day. A decrease in opioid consumption and an increase in dynamic comfort are part of the desired effects of ESP blocks. There is no strong evidence on ESP catheters, and therefore, they cannot be recommended as the first choice.

AOSRA-PM ESP block has a role to play in this patient. It would have to be a four-quadrant block since the incision is going to be large. The counterargument to not giving ESP block in this patient would be unpredictable spread and difficult access to the transverse processes, considering the nature of curvature and rotation of the spine. The block performed by the surgeon after exposing different layers and directly visualizing the transverse process is an attractive option. Again, unpredictable spread and inadequate time for the uptake of the local anesthetic are concerns for such a technique. Considering the difficulty we may face with opioid-based analgesia in this patient, it would be a prudent idea to use ESP block to accrue whatever benefit it may offer against the odds of difficult access and spread, particularly considering its safety profile.

AFSRA Continuous ESP blocks can be a very valuable modality and can be inserted by the surgeon postoperatively if not done preoperatively by the anesthetist. If single-shot ESP blocks are used, insertion at the end of surgery by the surgeon may be advantageous, giving a longer period of analgesia postoperatively. This is especially of value in resource-limited settings where ultrasound and perineural catheters or care for catheters may not be available. Injection at more than one level will improve the spread to cover the surgical area.

CAS ESPs can play a significant role in complex spine surgery as an adjunct to anesthesia and postoperative pain management. This regional anesthesia technique involves the injection of local anesthetic medication within the interfascial plane between the erector spinae muscle and the transverse process of the vertebra at a given level. This approach aims to provide analgesia by targeting the nerve roots and, to a variable degree, the paravertebral space. In complex spine surgery, ESPs may be performed by surgeons as part of a multimodal pain management strategy. Here are a few potential roles for ESPs in complex spine surgery:

- Preoperative pain control - ESPs can be administered before surgery to provide some pre-emptive analgesia. However, in this specific case, it would not seem to be the best option given the length of the operation and the multiple levels (ie, T2 to L2). In addition, there is a high likelihood that a lidocaine infusion may be utilized intraoperatively.

- Intraoperative analgesia - During complex spine surgery, ESPs can be used in combination with general anesthesia to provide intraoperative pain control. In this case, a single preoperative shot can be considered to reduce intraoperative and postoperative opioid consumption. However, the insertion of a catheter for continuous infusion is not likely going to be an option due to the risk of catheter damage during surgery. Alternatively, the surgeon may perform the block toward the end of the surgery to achieve immediate postoperative pain relief, with a subsequent block administered 24 hours later.

- Postoperative pain management - ESP can also be utilized for postoperative pain management in complex spine surgery. By providing targeted analgesia to the surgical site, these blocks can help reduce postoperative pain intensity and improve patient comfort, potentially leading to faster recovery and shorter hospital stays. In this specific case, given the extensive area and levels from T2 to L2, performing bilateral multi-level ESP single shots for each level seems not reasonable and might introduce a small risk of infection, which could be catastrophic. As noted above, continuous infusion may be an option if placed by the surgical team or anesthesia team.

Part 4: Perioperative Buprenorphine Management

- Would you decrease the buprenorphine doses or continue as prescribed perioperatively?

ASRA Studies suggest that stopping buprenorphine could increase the risk of return to use (relapse).22 Thus, currently, the recommendation is to continue buprenorphine throughout the perioperative period.21 There is less consensus regarding weaning vs not weaning the buprenorphine. She is taking 24 mg of buprenorphine a day. Binding studies suggest that at 24 mg, the availability of available opioid receptors is limited. 34 Thus, depending on the severity of her OUD, one could potentially decrease the dose or continue at the same dose. In my practice, I would recommend continuing at her current dose and using multi-modal techniques to help control her pain.

ESRA No change.

LASRA Only transdermal buprenorphine is available in Latin America. There are no other forms with or without naloxone. Therefore, we can only comment on their use based on available literature, not on real-world experience. Guidelines provided by ASRA or AAPM can give us some interesting suggestions.

AOSRA-PM The patient is taking 8 mg of buprenorphine three times a day. That would amount to 24 mg per 24 hours. Buprenorphine is a partial agonist with a stronger affinity (for mu receptors) and longer half-life compared to pure mu agonists that are routinely used during major surgeries such as this. At 16 mg per day, it has been found that sufficient receptors have been spared for the pure mu agonists to act upon for us to use them in the perioperative period to deal with the perioperative pain. It would be a rational argument to decrease the dose of buprenorphine to 16 mg per day to deal with the perioperative period. The other concerns in this period would be withdrawal symptoms and relapse of OUD. Sixteen milligrams per day would be a reasonable dose to not induce withdrawal symptoms and would be sufficient to act as a buffer to prevent relapse of opioid abuse during the postoperative period once the need for use of pure mu agonists decreases.

AFSRA We would likely continue her on the same dosage as before surgery if not changing to methadone. Decreasing the dose does hold the advantage of increased receptor availability for added full agonists during the perioperative period, especially at buprenorphine dosages above 16 mg per day, but this also increases the risk for cravings and relapse. It would be ideal to use other modalities to manage analgesia perioperatively rather than add opioids. If needed, additional opioids with high receptor binding affinity would still be effective, although higher doses may be required. If her risk for relapse is deemed low and sufficient other analgesic modalities are not available, decreasing the buprenorphine dose to 16 mg per day may be advisable.

CAS We recommend reducing buprenorphine to a daily dose of 8-16 mg over several weeks leading up to surgery. We point the reader to the Mayo Clinic proceedings article demonstrating the “sweet spot for analgesia,” which is 8-16 mg of sublingual buprenorphine.15 On the day of the surgery, Kaley would continue ideally on her 10-12 mg of buprenorphine and consider MMA, including regional anesthesia, both intraoperatively and postoperatively, with the understanding, as stated previously, that higher doses of opioids may be required. Postoperatively, we would return Kaley to her preoperative dose of buprenorphine as soon as possible prior to discharge. However, mu opioids may be required as needed, acknowledging that higher doses may be necessary for 2-4 days, followed by gradual tapering and close monitoring. We would consult a TPS, if necessary, and ensure follow-up with Kaley’s outpatient provider is coordinated before discharging her.

Part 5: Neuromonitoring and Anesthetic Implications

- The surgeon also told you that neuromonitoring will be used during surgery. Is this something that happens often at your institution? If so, how would this affect intra-operative anesthetic and analgesic management, if at all?

ESRA Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM), utilizing modalities like somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) and transcranial motor evoked potentials (TcMEP), is essential for assessing spinal cord function, particularly during scoliosis surgery with instrumentation, aiming to prevent potential damage. However, the sensitivity and quality of collected neurophysiological data are significantly influenced by the anesthetic technique employed; hence, it's crucial to maintain steady-state concentrations of anesthetic agents throughout surgery to avoid compromising signal measurement. Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) without neuromuscular relaxation is the current gold standard for IONM, while changes in physiological variables like temperature, hemodynamics, and ventilation can interfere with readings.35

Ultrasound-guided ESP block emerges as a safe alternative to epidural and paravertebral blocks, offering easily recognizable sonoanatomy and fewer complications. However, during long spine surgeries like scoliosis surgery, fluctuations in TcMEP may occur with ESP blocks, necessitating baseline TcMEP recordings post-ESP block placement to accurately assess changes.36

Yes, at our institution, it is common practice to record IONM data both before, after administering an ESP block, and during the surgical procedure, allowing for real-time assessment of neural integrity that informs perioperative management decisions to optimize patient care.

LASRA Definitely agree with such monitoring in an effort to decrease neurological complications after major spinal surgery.

It is available in Colombia, in major cities, and in academic-affiliated centers, but the number of neurosurgery centers in South America is less. Brazil is the leading country in such practice. TIVA techniques with rigorous use of NMB do not alter the evoked potentials. A basal response is often recorded before the administration of the NMB. Some patients with scoliosis can have muscular diseases sensitive in nature to depolarizing agents such as suxamethonium.

AOSRA-PM Neuromonitoring is used in surgeries where the surgeon is uncertain about the screw trajectory or attempts at de-rotation, and correction can produce undue stretching of the spinal cord and nerve roots. The surgeon can be alerted by the loss of neuromonitoring signals at such crucial steps in the surgery and can go on to perform a remedial action, such as removing the suspected screw or reversing the correctional forces. This is a huge improvement compared to the previously used ‘wake up’ test. MEP/SSEP monitoring allows immediate identification of interruption of neural transmission and can be used as many times as needed during the course of the surgery.

All major spine deformity corrections in our institution are carried out with the aid of neuromonitoring. It has helped us avert or reverse major neurologic deficits.