Approach to Regional Anesthesia for Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Problem-Based Learning Discussion

A 56-year-old female with a history of left hip osteoarthritis presents to the orthopedic clinic for follow up regarding her left hip pain. Her pain has been progressively worsening since her initial referral. An updated left hip X-ray shows a shallow acetabulum, with a lateral center-edge angle of 17° (normal 25°- 40°), and severe osteoarthritis. Today, she reports that the pain has significantly worsened in the last three months.

Over the course of two years, she has received multiple steroid injections and platelet rich plasma injections for pain control. Initially, the injections did significantly reduce the intensity and frequency of pain; however, they have become less effective. The orthopedic surgeon recommends total hip arthroplasty. The patient is agreeable but is concerned about the anesthesia required for the procedure. She has a history of severe postoperative nausea and vomiting due to anesthesia, as well as itching from opioids.

Her BMI is 27 kg/m2 with normal vitals. On physical examination, there is decreased range of motion in the left hip, and a FADIR test elicits significant pain in her groin. Left hip flexion is limited by pain (⅘). Otherwise, the strength and sensation to light touch of her bilateral lower limbs are intact.

Key Questions:

1. Describe the nerve supply of the hip joint capsule.

The hip joint capsule allows for a wide range of motion and is also responsible for much of the pain experienced in the hip. The nerve supply of the capsule is complex and derived from the lumbar plexus. Nerve supply can be distinguished by examining the various components of the capsule. The anterior hip capsule has many nociceptors, while the posterior hip capsule has more mechanoreceptors.1 The anterior hip capsule is primarily supplied by articular branches from the femoral, obturator, and accessory obturator nerves. On the other hand, the posterior hip capsule is primarily supplied by branches from the sciatic nerve, superior and inferior gluteal nerves, and nerve to the quadratus femoris. 1-3

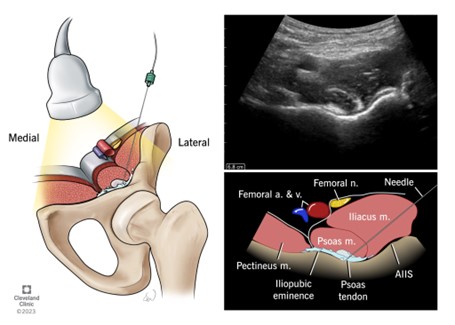

2. What is a PENG block and what are its targets? Describe the anatomical landmarks and technique associated with this block.

The Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) block is a regional anesthesia technique for postoperative analgesia. This block targets the articular branches of the hip capsule. The following steps describe the technique of the PENG block:1-3

- With the patient in supine position, place the probe transversely at the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and scan inferiorly to locate the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS). Next, the probe can be turned towards the pubic symphysis to find the iliopubic eminence of the ilium (IPES). During this time, the psoas tendon should also be located.

- A standard needle should be inserted with in-plane technique from lateral to medial, with needle tip targeted to rest between the psoas tendon and ilium.

- After negative aspiration, inject 15-20 mL of local anesthetic. Successful block can be characterized by a classic “lifting” movement of the psoas tendon and fluid spread in the plane.

- Caution should be taken to avoid damage to the femoral nerve or entry of the needle into the pelvic cavity.

Figure 1. Anatomical structures for the PENG block

Reproduced with permission from Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography

3. Describe advantages of the PENG block compared to other indicated regional anesthesia techniques for hip arthroplasty. Additionally, describe concerns associated with the PENG block.

The PENG block targets the articular branches of the hip capsule, leading to more complete analgesia of the hip joint, in comparison to techniques like the femoral nerve block, which does not capture the proximal contributions from the other nerves. Additionally, the PENG block targets nociceptive nerve branches but spares the motor branches, which can help with postoperative evaluation, early ambulation, and physical therapy participation. In elderly patients, atrophied muscles and less defined fascia may make the practical technique of femoral nerve and fascia iliaca blocks comparatively more difficult than the PENG block. Furthermore, several studies have found that the PENG block is associated with lower opioid consumption in patients after surgery compared to other blocks.1-3

Like all regional techniques, as those discussed below, general complications may include infection, bleeding, or local anesthetic systemic toxicity. A specific consideration of the PENG block is that intramuscular injection or injection of large volume of anesthetic (>20 mL) will increase risk for anterior thigh and quadriceps muscle weakness secondary to femoral nerve blockade. Additionally, as the injection point of the PENG block is close to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, care must be taken during local infiltration to the skin and during needle advancement to avoid injury to this nerve.1-3

Overall, it is important to examine each case on an individual basis. For some patients, multimodal analgesia may be better or safer than regional anesthesia intervention. While choosing an analgesic technique, providers should discuss goals of care with the patients in order to balance pain management with meeting functional goals.

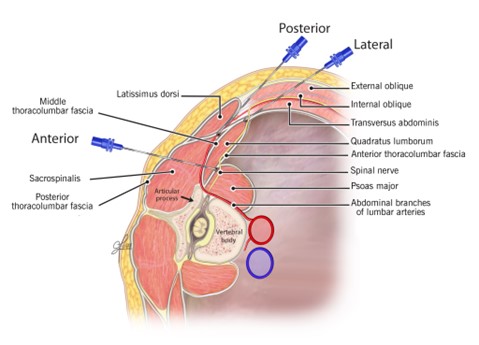

4. What is a Quadratus Lumborum Block? Describe the anatomical landmarks and technique associated with this block.

The Quadratus Lumborum (QL) block, which was first discussed and introduced in 2007, is an extension of the transversus abdominis plane block.4

The quadratus lumborum muscle itself is located posteriorly on either side of the spine, beginning inferiorly at the 12th rib and L1-L4 transverse processes and terminating at the superior border of the iliac crest. 5 The QL muscle is medial to the psoas muscle, lateral to the latissimus dorsi, and posterior to the erector spinae. The thoracolumbar fascia is anterior to the QL and psoas, continuing from the transversus abdominis fascia. The fascia has an inner layer which is continuous with the internal thoracic fascia and outer layer fusing with the arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. The middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia extends laterally to the lateral aspect of the QL and anterior to the latissimus dorsi. The posterior layer is behind the erector spinae muscles. It is important to note that the ventral rami of the spinal nerve roots travel between the QL and the thoracolumbar fascia.6

In regard to patient positioning, lateral decubitus is preferred over supine because it helps stabilize the ultrasound probe and needle while providing a larger area to better view neuraxial structures. 5 The hip can be abducted and laterally flexed on the same side of the block in order for the QL muscle to contract. The low frequency (2-6 MHz) array transducer can be used for ultrasound for adequate visualization of the three lateral abdominal muscles, QL muscle, and lumbar paravertebral structures. The marker on the transducer should be lateral to have a transverse view of the structures. When scanning between the iliac crest and subcostal margin, the probe should be moved. posteriorly to visualize the three abdominal muscles taper. The QL muscle should eventually appear along with the fascia transversalis.5 The transversalis fascia is hyperechoic, which will help to distinguish the kidney and abdominal contents. Scanning can also be done starting from the lumbar vertebrae, approximately 4 centimeters lateral to the spinous processes. This gives the classic “shamrock” sign, which is composed of the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae, erector spinae muscles, psoas major, and quadratus lumborum.

The QL can be seen at the inter-transverse process view and oblique transverse view at the transverse process. The inter-transverse view provides better visualization of the psoas. There are three approaches to the QL block: lateral, posterior, and anterior.5 Lateral QL block is when the needle is directed anterior to posterior, at the junction between where the three abdominal muscles taper and the QL; the local anesthetic is deposited at the anterolateral QL border, just outside the anterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Posterior QL block is when the needle is advanced in a similar fashion to the lateral QL, but local anesthetic is deposited posterior to the QL muscle and anterior to the erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, and serratus posterior inferior muscles; it is just outside of the middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Lastly, the Anterior QL block is performed when the needle is advanced posterior to anterior through the erector spinae and QL. Local anesthetic is deposited between fascial layers of the QL and psoas muscles. There is limited literature evaluating the safety and efficacy of these three techniques.

Figure 2. Needle trajectories for quadratus lumborum blocks

Reproduced with permission from Cleveland Clinic art photography department

5. What are the advantages of the Quadratus Lumborum Block? Additionally, describe concerns associated with the Quadrates Lumborum block.

Some studies suggest that compared to the transversus abdominis plane block, the quadratus lumborum block provides better pain relief, with improved pain scores, and potentially lasts longer.4

Literature has shown that compared to the transversus abdominis plane block, patients who receive a QL block have decreased overall opioid consumption.7 A single injection can cover multiple dermatomes and can provide visceral analgesia.7 Lastly, the different approaches of the QL block allow for variation and flexibility in achieving a successful block, depending on patient anatomy.

The QL block can pose a risk of prolonged motor block due to potential distribution to the lumbar plexus. However, motor block or lower extremity weakness has been observed in all QL block approaches.8 Hypotension has been occasionally observed along with local anesthetic systemic toxicity.8 Needle trauma is a potential risk with QL blocks due to the proximity to the pleura and kidney.8 Current literature has not shown the risk stratification of bleeding risk for each QL block approach.

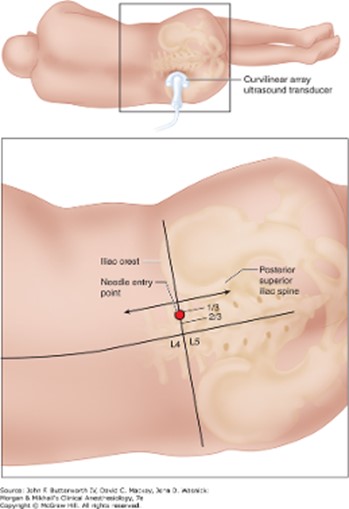

6. Describe the anatomy and procedure technique associated with a Lumbar Plexus Block. Additionally, describe concerns associated with the Lumbar Plexus block.

The lumbar plexus contains anterior primary rami of L1, L2, L3, and L4. In about 60% of the population, T12 can contribute to the lumbar plexus. As the L2, L3, and L4 roots of the lumbar plexus split off their spinal nerves and emerge from the intervertebral

foramina, they enter the psoas major muscle. Within the muscle, these roots then split into anterior and posterior divisions, which reunite to form the individual branches (nerves) of the plexus. These anterior rami form the iliohypogastric (T12,

L1), ilioinguinal (L1), genitofemoral (L1, L2), femoral (posterior division of L2, L3, L4), lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (posterior division of L2 and L3), and obturator (anterior division of L2, L3, L4) nerves.9,10 A lumbar plexus

block may not be the best method in isolation for a total hip arthroplasty, due to innervation of the posteromedial joint by branches of the sacral plexus and sciatic nerve.9 This procedure can be performed with ultrasound or landmark/stimulator

guidance. The landmark/stimulator guided technique is described below:

a. Patient is placed in the lateral decubitus on the opposite side of surgery, with the hip flexed 30° and the knee flexed 90°.

b. Needle insertion site is marked roughly 4-5 cm lateral to midline along the intercristal line.

c. At

this site, a 25-G spinal needle is introduced perpendicular to the skin and directed toward the ipsilateral transverse process. This needle serves as the depth and trajectory marker.

d. The block needle is attached to a neurostimulator, which

is set to 1.5 mA with 0.1 msec pulse duration at 2Hz, and an EKG electrode placed on the skin.

e. The block needle is then inserted and advanced 2 cm deeper than the depth achieved with the spinal finder needle.

f. Needle placement is

adjusted until a quadricep motor response is elicited. Precise positioning can be achieved by decreasing the current of the neurostimulation to 0.5mA, while still eliciting a quadricep motor response.

Figure 3. Positioning and anatomical landmarks for lumbar plexus block

Ultrasound guidance can be utilized, yet this technique is technically challenging as well. There are a few different US guided approaches including the trident view, paramedian transverse scan, and the shamrock method.11 Utilizing ultrasound

can decrease the risk of complications including intravascular injection and vascular injury while improving the accuracy of the injection. Additional side effects include hypotension, neuroaxial anesthesia, or retroperitoneal hematoma.

A continuous lumbar plexus block has been shown to be more beneficial than a single injection block for postoperative pain control.12 Additionally, patients with a continuous lumbar plexus block, when compared to a PCA or continuous femoral block, have significantly better pain control and participation during postoperative physical therapy.13 Due to the lumbar plexus block being technically challenging, researchers have compared this procedure to a continuous erector spinae block for postoperative pain control after a revision total hip arthroplasty. They found that there was no statistically significant difference in opiate consumption or pain scores.14 This is not a first line procedure because it is technically challenging and other aforementioned regional procedures can offer similar, if not better, pain control with less risk.

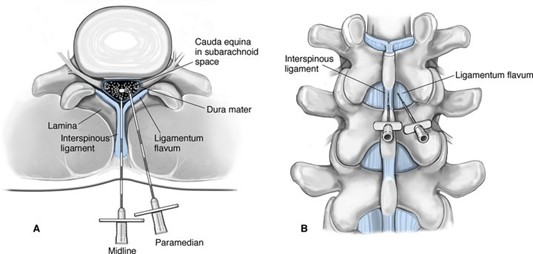

7. What is the goal of a spinal anesthetic? Describe the anatomical landmarks and technique associated with this procedure.

Spinal anesthesia describes a neuraxial procedure used as a regional technique for hip surgery. 15 Local anesthetic is placed in the post dural space, where cerebrospinal fluid is located. This is generally done in the lumbar spine region because

the conus medullaris is approximately located at L2 in adult patients and L3 in pediatric patients, whilst the thecal sac ends around S2/S3. This position decreases the risk of spinal cord injury.

The procedure is most commonly performed in the sitting position, but it can also be performed in the lateral decubitus or least commonly, prone position.16 Positioning

helps to optimize the trajectory of the needle insertion path between the spinal vertebrae. The patient should assume a flexed position to help open the interspace between the spinous processes. The level chosen to enter with the spinal needle should

be determined by palpation of anatomical landmarks. The iliac crest is determined as the anatomic landmark for L4.16 The space between two palpable spinous processes is the site for needle entry.

This is a strict, sterile technique, and so, using an antiseptic wash, adequate hand washing, mask, cap, and the use of sterile gloves is necessary.16 Cleaning should start

at the chosen needle entry site in a circular fashion, moving away from the site. Enough time should be given for the cleaning solution to dry. Drape placement should then be done to isolate the site. Local anesthetic should be injected subcutaneously,

creating a skin wheal at the site—midline or paramedian.

If assuming the midline approach, the spinal needle should be midline and advanced in a straight line once local anesthetic is given subcutaneously.17 The needle should

traverse the following structures: skin, subcutaneous fat, supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, and ligamentum flavum. The proceduralist may feel increased resistance through the layers with advancement of the spinal needle. Once going through

the ligamentum flavum, a pop may be felt through tactile feedback. This is when the epidural space is reached, and when providing an epidural, a loss of resistance would be felt using saline or air for injection. At this point, the proceduralist would

continue with needle advancement until the dural membrane is gone through. Once a pop is felt through the dura mater, the stylet should be removed to confirm cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flowing back. CSF coming back through the spinal needle is the

indication that the proceduralist has reached the target area to administer the spinal medication.

The paramedian approach involves subcutaneously injecting local anesthetic approximately two centimeters lateral from midline.17 The spinal needle then is advanced at an angle toward the midline. The following layers are traversed through the paramedian approach: skin, subcutaneous fat, and ligamentum flavum. The supraspinous and interspinous ligaments are bypassed through the paramedian approach, so the proceduralist may not encounter much resistance when the needle is traveling through the layers prior to the ligamentum flavum. Once the ligamentum flavum is reached, resistance may be felt until the same tactile pop sensation is felt with further needle advancement and CSF flow is seen coming back into the spinal needle. The spinal medication should then be administered.

Figure 4. Midline versus paramedian approaches for spinal anesthetics18

Figure 4. Midline versus paramedian approaches for spinal anesthetics18

It is important to note that there may be benefits to using ultrasound-guided techniques for neuraxial procedures in clinically difficult scenarios such as challenging lumbar anatomy secondary to surgeries, spine pathologies, obesity, or abnormal spine curvature.19 Evidence has shown that using ultrasound can decrease the number of attempts before success, predict the depth to the epidural space more accurately, and help facilitate mapping of the needle trajectory by identifying anatomical structures and lumbar interspaces. 20 However, there is not much literature in the use of ultrasound for spinal single-shot anesthesia.

8. What are the advantages of a spinal anesthetic? Additionally, describe concerns associated with the spinal anesthetic.

Spinal or neuraxial anesthesia offers some advantages compared to general anesthesia.21 However, literature has shown that there is generally no benefit to neuraxial compared to general anesthesia.22 Avoiding general anesthesia

in certain populations can be very beneficial, such as patients with significant respiratory pathologies or those with a difficult airway. It also can be a useful adjunct to general anesthesia for postoperative pain. Compared to general anesthesia,

the use of neuraxial anesthesia potentially offers better pain control than intravenous opioids, reduced need for systemic opioids, earlier return of bowel function, decreased bleeding, faster recovery and discharge, and enhanced participation

in physical therapy. These advantages are generally seen with any regional anesthesia technique.

The spinal anesthesia has associated risks such as hypotension due to sympathectomy, post-dural puncture headache although less likely given the smaller gauge spinal needle, and nerve damage, which is rare.23

Table 1: Summary of Regional Anesthesia Techniques for Hip Arthroplasty

| Type of Block | Target | Approach | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PENG | Articular branches in hip capsule | Place the probe at the ASIS and scan to locate AIIS and IPES. Using the in-plane technique from lateral to media, inject into the plane between the ischium and psoas tendon and observe the classic “lifting” of the tendon. | ● More complete analgesia to hip joint ● Spares motor branches, allowing for early ambulation ● Preserved ease in elderly patients and atrophied muscles ● Lower opioid consumption after surgery |

| Quadratus Lumborum | Thoracolumbar nerves around the quadratus lumborum muscle | Locate three abdominal muscles and scan until visualizing their taper and appearance of QL muscle and thoracolumbar fascia. Lateral: Inject into anterolateral QL border, outside anterior layer of thoracolumbar fascia. Posterior: Inject posterior to QL and in front of erector spinae, latissimus dorsi, and serratus posterior inferior muscles. Anterior: Inject between fascial layers of QL and psoas muscle. | ● Lower opioid consumption after surgery ● Coverage of multiple dermatomes ● Provides visceral analgesia ● Flexibility from varied approaches |

| Spinal | Spinal cord and nerve roots at L3/L4 or L4/L5 level (L5/S1 for Taylor approach) | Midline: Perform midline dural puncture and confirm CSF return before injecting medication. Paramedian: Insert needle 2 cm from midline and advance at angle towards midline. Perform dural puncture and confirm CSF return before injecting medication. Taylor: Insert needle 1 cm medial and inferior to posterior superior iliac spine and advance medially and cephalad towards midline. Perform dural puncture and confirm CSF return before injecting medication. | ● Successful block may allow for avoidance of general anesthesia ● Adjunct for postoperative pain ● Taylor approach: may be used if other approaches cannot be done or are not successful |

| Lumbar Plexus | Lumbar plexus, L1-L4 | Anatomy/stimulation guided: Insert spinal needle 4-5 cm lateral to midline along the intercristal line and touch down on the transverse process. Then insert the block needle with the stimulator attached. Advance 2 cm past spinal needle. When in the proper location, the needle should stimulate the quadricep muscle. | ● Decrease postoperative opiate use ● Early ambulation and participation with PT. |

Sources:

1. Kolli S, Nimma S, Kukreja P, Peng P. How I do it: pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block. ASRA News. 2023;47(2). doi:10.52211/asra080123.007

2. Berlioz BE, Bojaxhi E. PENG Regional Block(Archived) [Updated 2024 Oct 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565870/

3. The Hip (PENG) Block. NYSORA 2020. Available from: https://www.nysora.com/news/the-hip-block-new-addition-to-nysoras-web-app/

4. Blanco R. 271: Tap block under ultrasound guidance: the description of a “no pops” technique. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(5):130-130. doi:10.1016/j.rapm.2007.06.268

5. Elsharkawy H, El-Boghdadly K, Barrington M. Quadratus Lumborum Block. Anesthesiology. 2019;130(2):322-335. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000002524

6. Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar

fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. J Anat. 2012;221(6):507-536. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x

7. Blanco R, Ansari T, Riad W, Shetty N. Quadratus Lumborum Block Versus Transversus Abdominis Plane Block for Postoperative

Pain After Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(6):757-762. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000495

8. Elsharkawy H, El-Boghdadly K, Barrington M. Quadratus Lumborum Block: Anatomical Concepts, Mechanisms,

and Techniques: Erratum. Anesthesiology. 2024;141(6):1226-1226. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000005221

9. Polania Gutierrez JJ, Ben-David B. Lumbar Plexus Block. [Updated 2023 Jan 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls

Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556116/

10. Vloka J, Tsai T, Hadzic A. Lumbar Plexus Block

– Landmarks and Nerve Stimulator Technique. NYSORA.https://www.nysora.com/topics/regional-anesthesia-for-specific-surgical-procedures/lower-extremity-regional-anesthesia-for-specific-surgical-procedures/lumbar-plexus-block/

11. Karmakar M. Lumbar Paravertebral Sonography and Considerations for Ultrasound-Guided Lumbar Plexus Block. https://www.nysora.com/techniques/lumbar-paravertebral-sonography-considerations-ultrasound-guided-lumbar-plexus-block/

12. Watson M, Mitra D, Mclintock T, Grant S. Continuous Versus Single-Injection

Lumbar Plexus Blocks: Comparison of the Effects on Morphine Use and Early Recovery After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30(6):541-547. doi:10.1016/j.rapm.2005.06.006

13. Marino J, Russo J, Kenny M, Herenstein R, Livote E, Chelly JE. Continuous Lumbar Plexus Block for Postoperative Pain Control After Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Jt Surg-Am Vol. 2009;91(1):29-37. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00079

14. Chen A, Kolodzie K, Schultz A, Hansen EN, Braehler M. Continuous Lumbar Plexus Block vs Continuous Lumbar Erector Spinae Plane Block for Postoperative Pain Control After Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty. Arthroplasty Today. 2021;9:29-34.

doi:10.1016/j.artd.2021.03.016

15. Neuman MD, Feng R, Carson JL, et al. Spinal Anesthesia or General Anesthesia for Hip Surgery in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(22):2025-2035. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2113514

16. Brull R, Macfarlane AJR, Chan VWS. Spinal, epidural, and caudal anesthesia. In: Miller’s Anesthesia.

9th ed. Elsevier.2020: 1413-49.

17. Chin A, van Zundert A. Spinal anesthesia. In: Hadzic A, ed. Hadzic’s Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education. 2017.

18. Valovski IT, Valovska

A. Spinalanesthesia. In: Vacanti C, Segal S, Sikka P, Urman R, eds. Essential Clinical Anesthesia. Cambridge University Press; 2011:340-348.

19. Chin KJ, Perlas A, Chan V, Brown-Shreves D, Koshkin A, Vaishnav V. Ultrasound Imaging Facilitates

Spinal Anesthesia in Adults with Difficult Surface Anatomic Landmarks. Anesthesiology. 2011;115(1):94-101. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31821a8ad4

20. Perlas A, Chaparro LE, Chin KJ. Lumbar Neuraxial Ultrasound for Spinal and Epidural Anesthesia:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(2):251-260. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000184

21. Hunie M, Fenta E, Kibret S, Teshome D. The Current Practice of Spinal Anesthesia in Anesthetists at a Comprehensive Specialized

Hospital: A Single Center Observational Study. Local Reg Anesth. 2021;Volume 14:51-56. doi:10.2147/LRA.S300054

22. Vail EA, Feng R, Sieber F, et al. Long-term Outcomes with Spinal versus General Anesthesia for Hip Fracture Surgery: A Randomized

Trial. Anesthesiology. 2024;140(3):375-386. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004807

23. Doelakeh ES, Chandak A. Risk Factors in Administering Spinal Anesthesia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. Published online December 4, 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.

Chandak A. Risk Factors in Administering Spinal Anesthesia: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. Published online December 4, 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.49886