Neurological Examination

Author

Joshua Wellington, MD

Medical Director

Indiana University Pain Medicine Center

Assistant Professor of Clinical Anesthesia and

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Introduction

A thorough examination of a patient with pain complaints is necessary for comprehensive evaluation and formation of treatment recommendations. The appropriate neurological examination is often one of the most essential components of this process.

There are six elements of the neurological examination cranial nerve function, cerebellar function, sensory function, motor function, reflexes, and gait. Of these, the three most pertinent areas of examination for patients with pain complaints are:

- sensory function,

- motor function, and

- reflexes.

Of course, if a patient's primary complaint is of facial pain then evaluation of cranial nerves will be most important. However, for the most common complaints (i.e. back/leg and neck/arm pain), a focused and systematic examination of sensory, motor, and reflexes will yield the information required for making a diagnosis. For the purposes of the focused neurological examination for the patient with pain complaints, the emphasis will be placed on assessment of these three modalities.

Sensory Examination

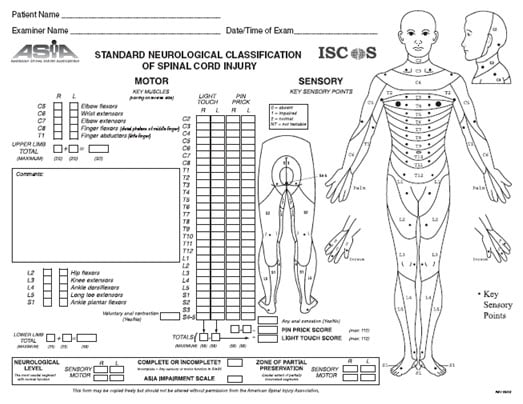

The order of examining each component within the neurological system is likewise important. When examining a patient, it should be considered that report of sensory testing is often the most subjective of the elements of the neurological examination. Although testing for temperature, vibration, touch, proprioception, etc. are important for a complete neurological examination, pinprick testing alone will usually suffice for the purpose of extracting the most information quickly from a patient with pain complaints. Dermatomal testing of sensation is based on the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) classification of key sensory points (Figure1)[1].

Figure 1. ASIA Standard Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury.

Sensory testing can be performed quickly and efficiently based on these key sensory points. A broken tongue blade or cotton tipped applicator will usually work quite well to assess pinprick sensation. Of course, so will a pin. However, be mindful not to draw blood and discard the instrument after each patient. When testing for sensory function, it is important to assess each dermatomal level on both sides at the same time. The goal of sensory testing is to quickly discern whether there is a difference in symmetry. For example, a decrease (hypoalgesia) in perception at a certain dermatomal level on one side may be indicative of a radiculopathy, whereas an increase in perception (hyperalgesia or allodynia) could relate to a condition such as Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Focusing on the more common complaints of neck/arm and back/leg pain, the sensory examination may be honed to testing of the upper and lower extremities to test the cervical and lumbar dermatomes, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Focused Sensory TestingDermatome points to test with pinprick |

Upper extremity |

C5 Lateral epicondyle |

C6 Thumb (dorsal surface) |

C7 Middle finger (dorsal surface) |

C8 Little finger (dorsal surface) |

T1 Medial epicondyle |

Lower extremity |

L1 Proximal medial thigh at groin |

L2 Anterior mid-thigh |

L3 Medial knee |

L4 Medial malleolus |

L5 1st webspace of the foot |

S1 Lateral malleolus |

Motor Examination

Examination of motor function is the next essential part of a neurological assessment. Proper grading of muscle strength is imperative at the time of initial examination to document deficits for diagnosis and future comparison (Figure 3). It is important to assess a patient's motor power based on the clinician's assessment of his/her potential muscle strength. For example, one must assess a 90-year old woman differently than a 25-year old man based on their potential muscle strength relative to the examiner.

| 5 | Normal strength against resistance through a full range of motion |

| 4 | Patient able to give some resistance, but examiner can overcome patient's strength |

| 3 | Patient unable to give significant resistance to examiner, but can move the muscle through its complete range of motion against gravity |

| 2 | Patient unable to give resistance to examiner, but can move the muscle through its complete range of motion with gravity eliminated |

| 1 | Patient unable to give resistance to examiner, but can move the muscle through partial range of motion with gravity eliminated |

| 0 | No movement |

It is fundamental to understand the appropriate grading of muscle strength to accurately assess motor function. In order to avoid variability between examiners, it is recommended to use only whole numbers. Specifically, avoid grading with pluses and minuses as this only has potential value if the same examiner is testing the patient every time.

Upon understanding the principles of muscle strength grading, an examiner is challenged to quickly and efficiently focus on the myotomes that may represent the more commonly affected cervical and lumbar spinal levels. Assessment of the C5-T1 myotomes and L2-S1 myotomes will usually be sufficient for evaluation. Using the ASIA classifications, key muscles may be tested related to these myotomes (Figure 4).

| Muscle(s) to test |

| Upper extremity |

| C5 Elbow flexors |

| C6 Wrist extensors |

| C7 Elbow extensors |

| C8 Finger flexors (middle finger) |

| T1 Finger abductors (little finger) |

| Lower extremity |

| L2 Hip flexors |

| L3 Knee extensors |

| L4 Ankle dorsiflexors |

| L5 Great toe extensors |

| S1 Ankle plantar flexors |

When testing for muscle strength, it is important to have both the patient and the examiner in a comfortable position. It is quite difficult to accurately assess strength if either the examiner or the patient is off balance. It is important to stabilize the joint proximal to the muscle being tested then apply sufficient force against the muscle being tested. A common pitfall is to place too little force against a tested muscle and miss subtle weakness. Another consideration when evaluating muscle strength is to always test a muscle in eccentric contraction and not in concentric contraction. Testing a concentric contraction may cause the examiner to fail to notice slight weakness which can be further compounded by awkward positioning. An eccentric contraction occurs when muscle fibers are lengthened; conversely, a concentric contraction occurs when muscle fibers are shortened. Therefore, when testing strength, have the patient contract the muscle being tested and then try to overcome it. For example, have a patient flex the biceps muscle and then the examiner tries to pull it into extension. This technical consideration allows the examiner to discern subtle differences in muscle strength that might go unnoticed if testing with concentric contractions.

Reflex Examination

Examination of the reflexes is the last essential modality of a focused neurological assessment. Reflexes are graded on a scale (0-4) based on the briskness of reaction (Figure 5). The range of normal also includes hyporeflexic (1+) and hyperreflexic (3+) as long as the response is symmetric.

| 4+ | Very brisk jerk with clonus (pathologic) |

| 3+ | Brisk jerk |

| 2+ | Normal jerk |

| 1+ | Slight jerk |

| 0 | Not present |

Examination of the muscle stretch reflexes is usually easiest with the patient sitting. Support the limb to be tested and maintain the musculotendonous junction in a state of slight passive stretch. The tendon may be tapped directly or tap your finger/thumb overlying the tendon. The benefit of the latter is that subtle jerks may be perceived by the examiner's touch that may otherwise go unnoticed. Subtle reflex responses may be augmented with a distracting motor stimulus. For example, a patient may be asked to isometrically pull one hand against the other with fingers flexed into a hook-like form and interlocked (Jendrassik maneuver) or clench the jaw or fist immediately prior to the tendon tap. Key points for muscle stretch reflex testing are listed in Figure 6.

| Upper extremity |

| C5, C6 Biceps reflex |

| C5, C6 Brachioradialis reflex |

| C7, C8 Triceps reflex |

| Lower extremity |

| L3, L4 Patellar reflex |

| L5 No easily elicited reflex |

| S1 Achilles reflex |

The clinical correlation of reflex changes depends on the site of pathology. Hypoactive or absent reflexes are indicative of dysfunction in the afferent or efferent limb of the segmental (peripheral nervous system) pathway of the reflex arc (i.e. radiculopathy). Pathologic hyperactive reflexes are a sign of suprasegmental (central nervous system) dysfunction (i.e. spinal cord/brain injury).

Summary

Although discussion of sensory function, motor function, and reflexes has been in terms of a single spinal level relating to a specific dermatome, myotome, or reflex response, one must consider that there may be considerable overlap of adjacent spinal levels. For example, although testing of the patellar reflex is described in terms of its relation to L4, there may be overlap of L3 and L5 contributing to this reflex. The same is true for every dermatome and myotome. If an anomaly is noted, one must consider that the levels above or below the tested level may be causative or contributing given the degree of individual variability.

The implementation of a logical, systematic, and efficient neurological examination is paramount when examining a patient with pain complaints. Depending upon the patient's symptoms and complaints, a more detailed neurological examination may be required. By focusing on the three modalities discussed, a diagnosis can often quickly be revealed in most patients.

References

- American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA). Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI Worksheet (Dermatomes Chart), Atlanta, GA, 2006.

- Glick, TH. Neurologic Skills: Examination and Diagnosis. Blackwell Scientific Publications: Cambridge (MA), 1993, pp 105-142, 159-174

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top