The Glucagon-Like-Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and the Role of Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS)

Cite as: Weber M. The glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists and the role of point-of-care ultrasound. ASRA Pain Medicine News 2023;48. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110123.007.

Background

It is unusual for a diabetes medication to provoke as much discussion in the anesthesia community as the mainstream press, but that has been the case for the increasingly popular glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA). These medications developed for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus replicate the action of glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1), a gut derived incretin hormone that stimulates insulin, suppresses glucagon, and reduces appetite and food intake.1 Additional benefits include their efficacy at improving HbA1C and reducing the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events.2 However, their current popularity is not due to their role as diabetes medications, but instead their potential for contributing to significant weight-loss in users with and without diabetes.

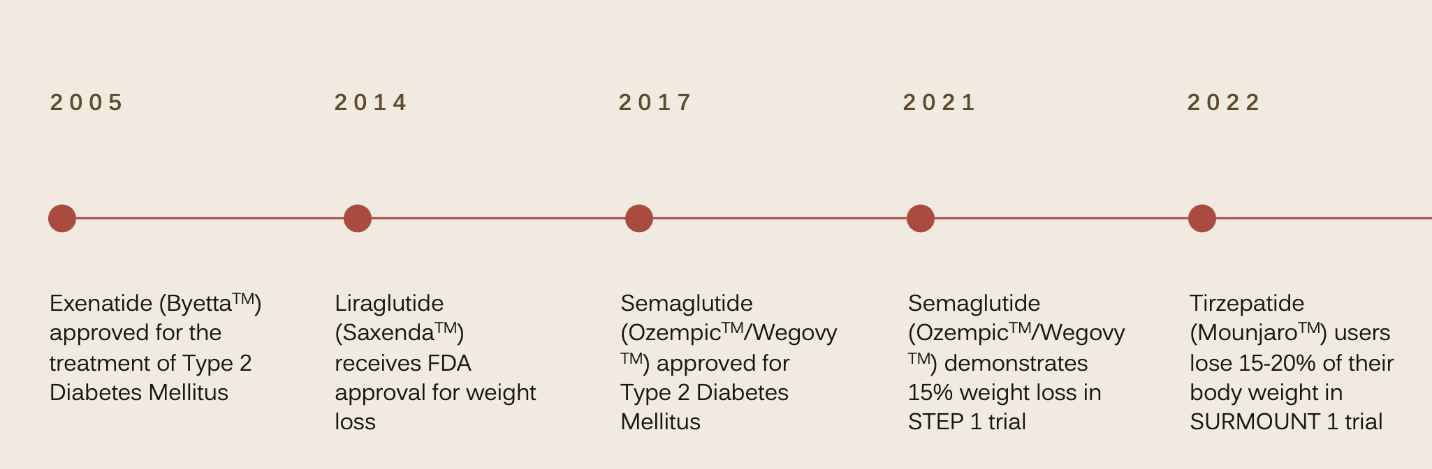

Despite their recent attention, the GLP-1RA are not an entirely new class of medications. Exenatide, (Byetta™) a short-acting, twice-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist, was approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in 2005 with additional longer-acting versions introduced in 2009 and 2014 as once-daily liraglutide (Saxenda™,Victoza™) and once-weekly dulaglutide (Trulicty™). Since then, once-weekly semaglutide (Wegovy™, Ozempic ™) was approved in 2017 and once-weekly tirzepatide (Mounjaro™) was approved in 2022 as the first dual incretin agonist, a GLP-1 receptor agonist/glucose dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonist. A full list of the GLP-1 receptor agonists can be found in Table 1.

| Name | Dosing schedule | Half-life |

| Short Acting GLP-1 Receptor Agonist | ||

| Exenatide (Byetta™) | Twice-daily injection | 2.4 hours |

| Long Acting GLP-1 Receptor Agonist | ||

| Liraglutide (Saxenda™*, Victoza™) | Once-daily injection | 13 hours |

| Dulaglutide (Trulicity™) | Once-weekly injection | 5 days |

| Semaglutide (Ozempic™,Wegovy™*) | Once-weekly injection | 7 days |

| Dual GLP-1 Receptor Agonist/Glucose Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide Agonist | ||

| Tirzepatide (Mounjaro™) | Once-weekly injection | 5 days |

| Oral GLP-1 Receptor Agonist | ||

| Semaglutide (Rybelsus™) | Once daily by mouth | 7 days |

*Indicates drug has FDA approval for weight loss

Although much of their recent popularity stems from their promise as potent weight loss medications, the earliest GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide did not demonstrate this potential.3 Liraglutide was the first GLP-1RA to earn FDA approval for weight loss in 2014 after users experienced 8% weight loss in clinical trials, but this modest benefit did not lead to a massive increase in its use.4 The real shift came after the publication of the STEP 1 trial in 2021, showing semaglutide (Ozempic ™) users experienced a weight reduction of 10% after 6 months of treatment and 15% after 16 months of treatment.5 Semaglutide’s promise as a life-altering medication for people struggling with excess body weight led to a widespread surge in its popularity and use. Since then, the newest GLP-1 receptor agonist, tirzepatide, has surpassed even semaglutide’s impressive effects with the 2022 Surmount 1 trial demonstrating tirzepatide users lost an impressive 15-21% of their body weight.6 Currently only liraglutide and semaglutide hold FDA indications for weight-loss in non-diabetic patients, but tirzepatide is currently on fast-track for approval. A timeline for this history can be seen in Figure 1.

Perioperative Concerns

Despite their impressive efficacy and favorable safety profile, the GLP-1 receptor agonists present risks to patients undergoing anesthetic care. The GLP-1RA replicate the action of native GLP-1, which acts peripherally to slow glucose excursion from the stomach into the duodenum thereby improving postprandial glycemic control.1 In physiologic conditions, native GLP-1 is degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) after a few minutes; however, the GLP-1RA do not undergo the same rapid breakdown. 1,7 As a result, users can experience clinically significant gastroparesis with significant implications for patients undergoing anesthesia.3,8 Initially this delayed gastric emptying was thought to be less prominent in the long-acting GLP-1RA, but this does not appear to be the case.8 Endoscopy studies have revealed that patients taking long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists have an increased incidence of residual gastric contents present despite fasting prior to their procedures.9,10 One of these studies evaluated a small cohort of semaglutide users undergoing endoscopy and found that 24% had residual gastric contents present on exam versus 5% in the non-semaglutide cohort nearly quintupling the incidence.9 Of the cohort with residual gastric content, 85% had solid content present despite fasting appropriately prior to their procedures.

Endoscopy studies have revealed that patients taking long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists have an increased incidence of residual gastric contents present despite fasting prior to their procedures.

Although it is understandable to attribute these findings to underlying disease, especially in patients with diabetes, capsule studies in patients with type 2 diabetes have demonstrated that diabetic patients without pre-existing gastroparesis will develop statistically significant delays in gastric transit time after treatment with a GLP-1 agonist.11 Moreover, an increasing number of nondiabetic, nonobese patients are using the GLP-1RA for weight-loss, who would not be expected to have underlying gastroparesis. This risk is not insignificant. There have been three reports in the literature of anesthetic complications related to residual gastric content in patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists in the last 6 months. One patient taking tirzepatide experienced clinically significant emesis requiring urgent conversion to general anesthesia and overnight admission, one patient taking semaglutide aspirated solid gastric content requiring bronchoscopy and ICU admission, and one patient taking semaglutide, who had fasted twenty hours from solids and eight hours from liquids, regurgitated a large volume of clear liquid upon induction, requiring bronchoscopy but fortunately with no further complications.12-14

Discussion

In response to the widespread discussion about the risks these medications pose, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recently released “Consensus-Based Guidance on Preoperative Management of Patients (Adults and Children) on Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 taking (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists.” For patients receiving once-weekly injections, ASA recommends holding the dose a week prior to surgery, and for those using once-daily medications, ASA recommends holding the dose the day of surgery.15 For patients undergoing elective procedures who present with gastrointestinal symptoms, ASA recommends delaying the procedure.15 In patients who did not hold their medications but are asymptomatic, ASA suggests discussing the risks and benefits with the patient and surgeon, following “full stomach” precautions, or if possible, evaluating the patient with gastric ultrasound.15

Gastric point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a simple, easily reproducible tool for assessing the presence and nature of gastric contents, and the technique has been discussed in a recent article in this newsletter.16 It offers significant benefit in this patient population as POCUS allows anesthesiologists to risk stratify patients allowing them to better determine and provide appropriate care. Since its introduction by Perlas et al in 2009, it has been promoted as a valuable exam that can provide reliable and reproducible insight into gastric contents.17 To perform a gastric POCUS exam, the gastric antrum is visualized with a 2-5-MHz curved-array probe with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position to provide the most accurate assessment of the gastric contents. The ultrasound probe is placed in a sagittal orientation in the epigastric area and then slid slightly to the right of midline to locate the gastric antrum. From this view, the liver, pancreas, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and aorta will be visualized. An empty stomach will appear flat with the thick hypoechoic muscularis propria visualized giving a characteristic “bull’s eye” appearance. Thick fluid or solid content will appear as heterogeneous, hyperechoic ultrasonographic material, and clear fluid will appear as hypoechoic content distending the gastric walls.18 Clear fluid up to 1.5mL/kg is consistent with baseline gastric secretions and offers a low risk of aspiration. 19 To estimate the volume of clear liquids and assess risk, the cross-sectional area of the stomach can be measured and correlated using the Perlas nomogram.18,19

Not every patient who presents for anesthetic care taking a GLP-1RA will have residual gastric content present, but POCUS presents an easy way to risk stratify patients and provide safer anesthetic care to this population. POCUS offers an easy tool to qualitatively assess the nature of gastric contents quickly and reliably. If the exam reveals a large volume of clear liquids (>1.5 mL/kg), thick-liquids, or solid content, the risk of aspiration is increased. Depending on the urgency of the case, patients could be offered a regional technique without sedation, or they should undergo general anesthesia with a rapid sequence intubation to secure the airway. Nasogastric tube placement in the setting of excess clear liquids or thick solids can also be considered.

Conclusion

The rise in the popularity of the GLP-1RA is due to a confluence of factors. The obesity epidemic and these medication’s potential for profound weight-loss are unprecedented outside of bariatric surgery. Their popularity coincides with the rise of social media platforms and telehealth capabilities that were difficult to imagine when the GLP-1 receptor agonists were first developed. Nor will this popularity be transitory. These medications will continue to garner attention as their use expands. Besides their efficacy for weight-loss and diabetes management, the GLP-1RA have demonstrated promise in the treatment of alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder due to their effects on central dopamine pathways.20 With off-label use and widespread demand for these medications, drug shortages have been rampant with the FDA reporting that semaglutide has been in shortage since August 2022 with 373,000 prescriptions filled in February 2023 up 111% since 2022.21 As drug shortages ease, anesthesiologists will increasingly encounter patients taking these medications in the perioperative space. Further data and guidelines will come with time, but in the interim, gastric POCUS provides an invaluable tool to assess risk and provide safe, quality care to our patients.

Marissa Weber, MD, is an assistant professor of anesthesiology in the division of regional anesthesia and acute pain medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, NY.

References

- Marathe CS, Rayner CK, Jones KL, et al. Relationships between gastric emptying, postprandial glycemia, and incretin hormones. Diabetes Care 2013;36(5):1396-405. https://doi.org/2337/dc12-1609

- Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2022;45(11):2753-86. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci22-0034

- Holst JJ. Long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist-status December 2018. Ann Transl Med2019;7(5):83. https://doi.org/21037/atm.2019.01.09

- Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with Type 2 Diabetes: The SCALE diabetes randomized clinical trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2016;315(1):90]. JAMA. 2015;314(7):687-99. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.9676

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N Engl J Med 2021;384(11):989-1002. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med 2022;387(3):205-16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2206038

- Little TJ, Pilichiewicz AN, Russo A, et al. Effects of intravenous glucagon-like peptide-1 on gastric emptying and intragastric distribution in healthy subjects: relationships with postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91(5):1916-23. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-2220

- Jones KL, Huynh LQ, Hatzinikolas S, et al. Exenatide once weekly slows gastric emptying of solids and liquids in healthy, overweight people at steady-state concentrations. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020;22(5):788-97. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13956

- Silveira SQ, da Silva LM, de Campos Vieira Abib A, et al. Relationship between perioperative semaglutide use and residual gastric content: A retrospective analysis of patients undergoing elective upper endoscopy. J Clin Anesth 2023;87:111091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111091

- Kobori T, Onishi Y, Yoshida Y, et al. Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment with gastric residue in an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. J Diabetes Investig 2023;14(6):767-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.14005

- Nakatani Y, Maeda M, Matsumura M, et al. Effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist on gastrointestinal tract motility and residue rates as evaluated by capsule endoscopy. Diabetes Metab 2017;43(5):430-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2017.05.009

- Weber M, Siddarthan I, Mack PF. Clinically significant emesis in a patient taking a long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonist for weight loss. Br J Anaesth 2023;S0007-0912(23)00237-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2023.05.005

- Klein SR, Hobai IA. Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report. Can J Anaesth 2023;70(8): 1394-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02440-3

- Gulak MA, Murphy P. Regurgitation under anesthesia in a fasted patient prescribed semaglutide for weight loss: a case report. Can J Anaesth 2023;70(8):1397-1400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02521-3

- Joshi G et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists Consensus-Based Guidance on Preoperative Management of Patients (Adults and Children) on Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists. ASA News. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative?&ct=35a9a5ebab26036f5f138d72097aa311b6152b3edc969d1da7abf5067c68205ea0bcddd13c0af31d428d7a2f077b5e207bd482871f174fd1bab35a5f2f42c27a. Published June 29, 2023.

- Perlas A, Kruisselbrink R. POCUS spotlight: gastric ultrasound. ASRA News 2021;46. https://doi.org/10.52211/asra110121.065

- Perlas A, Chan VW, Lupu CM, et al. Ultrasound assessment of gastric content and volume. Anesthesiology2009;111:82-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a97250

- Perlas A, Davis L, Khan M, et al. Gastric sonography in the fasted surgical patient: a prospective descriptive study. Anesth Analg 2011;113(1):93-7. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e31821b98c0

- Perlas A, Arzola C, Van de Putte P. Point-of-care gastric ultrasound and aspiration risk assessment: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth 2018;65(4):437-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-017-1031-9

- Klausen MK, Thomsen M, Wortwein G, Fink-Jensen A. The role of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) in addictive disorders. Br J Pharmacol 2022;179(4):625-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.15677

- Choi A, Wu H. Ozempic prescriptions can be easy to get online. Its popularity for weight loss is hurting those who need it most. CNN Health. https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/17/health/ozempic-shortage-tiktok-telehealth/index.html. Published March 17, 2023.