Anesthesia in Ambon: The Challenges and the Mission

I’d like to introduce myself and my project. My name is Steve Coppens. I am a locoregional anesthesiologist, I do mostly pediatrics, and I work in the University Hospitals of Leuven, where I am the director of Locoregional Anesthesia. For several years now I have been involved in a project in Ambon, Indonesia, with a dedicated team of two plastic reconstructive surgeons, myself, nurses, translators, and physiotherapists. Ambon is a remote island. It lies in the Banda Sea and is part of the Indonesian Maluku Islands, which are actually closer to Darwin, Australia, or Papua New Guinea than to the capital in Djakarta. Hospital settings in this region are generally very primitive—think pre–1970s era anesthesia. Most of the population is very poor and has no access to standard medical care. Owing to genetic predisposition, there are more cleft lips and cleft palate patients here than in Europe or the United States. There are also numerous cases of severe burn wounds due to the presence of highly unreliable electrical plants causing a fire hazard and due to the fact that most people still use primitive oil lamps. The villages or Kampongs are still mostly filled with fast-burning wooden huts, making this an extremely dangerous environment for severe fires and burn victims. Our team is not here to treat the immediate effect of the burn wounds, and the hospitals on the island are ill equipped at handling these anyway. Most people die because of lack of treatment. Those that do survive, however, are left with scar tissue–forming contractures that can severely impede normal life.

Though the conditions are primitive, we strive to provide a high standard of care. We ensure that patients get sufficient and adequate follow-up and pain relief. It is here where regional anesthesia can be of great assistance. Although we don’t do catheter-based techniques, owing to the hygienic standards and logistics, we do offer repeated blocks to patients who have extensive repairs and surgeries. Most patients receive a general anesthetic because of the duration of procedures and uncomfortable/primitive operating tables. The pediatric blocks are all performed under general anesthesia. We normally use landmarks and neuro-stimulation to place blocks in this population and often avoid neuromuscular blockade for this reason (Figure 1).

We have had to perform our blocks in some very difficult circumstances, as Figure 2 clearly shows. We were in the middle of performing a sciatic nerve block at the end of surgery, before the patient would get a cast. At that moment all electricity in the operating room failed, and we had to use our battery-packed headlamps while checking that our ventilator was still properly functioning. It is in these moments that good and thorough understanding of anatomy can help into performing a landmark-based, neuro-stimulator technique as fast as possible!

For our cleft palate repairs, we often do blocks as well as for analgesia. We use landmarks and palpation to place submental and suborbital blocks intraoperatively. With difficult airway patients, we use landmarks again to do airway blocks.

As for follow-up, we let all our patients stay in the recovery room overnight on the first day of surgery (Figure 3). Our recovery room actually was fit with air conditioning, which is sadly lacking in the wards. This not only allows us to follow-up on the block and the overall pain scores but also diminishes the chance of infections and complications, as the hygiene on the wards is poor. Equipped with only some small pulse oximeters, the recovery room is one of my primary concerns. Most of the problems arise postoperatively, and we tend to closely watch those patients who need it most. It is also the place where we evaluate the blocks or do rescue blocks or reblocks before letting the patients leave for the wards.

The repeated blocks are performed under monitoring and careful dosages. We do not do any blocks outside of the recovery room/operating room complex because of the dire circumstances, hygiene, and lack of safety. We have lipid rescue medication for local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) and a protocol in place if the need ever arises. But being careful with dosages and rigorous aspiration, using incremental doses, and relying on experience has helped us avoid needing to use lipid rescue. Preventing LAST is an absolute priority, as having a resuscitation situation in these hospitals is always dire even if you proceed according to protocol. Follow-up and intensive care unit is nonexistent as we know it.

For blocks, we have a cart with our local anesthetics, some sterile sheets, all needles, and our essential neuro-stimulator (of which we only have the one). Also, it is the place where we store our lipid rescue and protocols. We do continuous monitoring of pulse oximetry, however, as we do not have electrocardiogram monitoring. We are attentive to patient heart rate with the pulse oximetry when doing blocks and also take a few non-automated blood pressure measurements with our stethoscope.

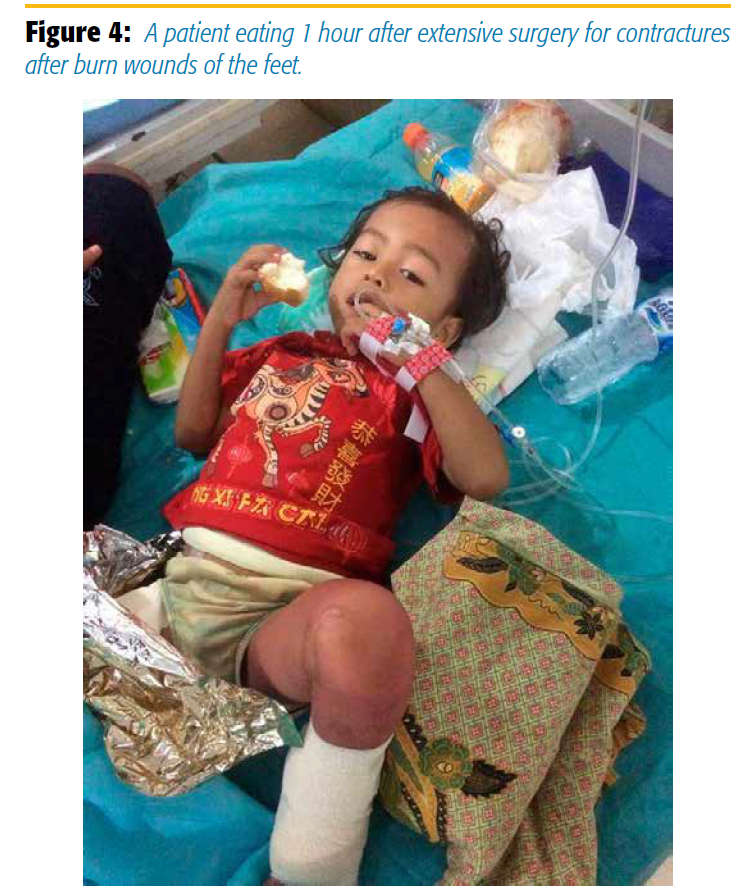

On a few of the pictures of the recovery ward you can sense how much comfort our blocks give these patients. Figure 4 shows a child 1 hour postoperatively who just received extensive surgery for contractures after burn wounds of the feet. The child is already eating after low-dose anesthesia and has no pain whatsoever, after receiving bilateral popliteal blocks intraoperatively.

One boy who couldn’t dress himself, because of intense third-degree burn wounds (Figure 5), was mobilized and taken through extensive reconstructive surgery under general anesthesia and received an upper trunk supraclavicular block. He is now a boy who proudly shows his new skills, without ever having had a lot of pain during his surgery and rehabilitation owing to repeated blocks.

Cleft palate and lip repairs are very rewarding. We are giving a beautiful smile back to these lovely children while giving them optimal pain control with the infraorbital and submental blocks (Figures 6). We find there is minimal postoperative pain, and the rate of releasing of sutures is practically zero. This is important because of the limited resources our team has and because we absolutely want to avoid redo surgeries. We visit these children on the second postoperative day on the wards, and they will go home the next day. A control nurse, who stays 1 month longer than our team, does one final check at home on the fourth week.

Performing anesthesia in this environment is rewarding and challenging. I find the use of regional anesthesia provides elegance to care in difficult circumstances for patients and providers.